Universal Design for Learning

An Inclusivity Theme Page

Universal Design for Learning

Inclusive education can be approached through the lens of Universal Design for Learning (UDL), as both intend to create a learning environment designed for a diversity of learners, rather than retrospectively making adaptations to accommodate specific students (Advance HE 2018).

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a set of principles for curriculum development that give all individuals equal opportunities to learn. The goal of UDL is learner agency that is purposeful and reflective, resourceful and authentic, strategic and action-oriented (CAST 2024). UDL provides a blueprint for creating instructional goals, methods, materials, and assessments that work for everyone – not a single, one-size-fits-all solution but rather a flexible approach that means learning can be customised and adjusted for individual identities and needs (UDL on Campus 2022).

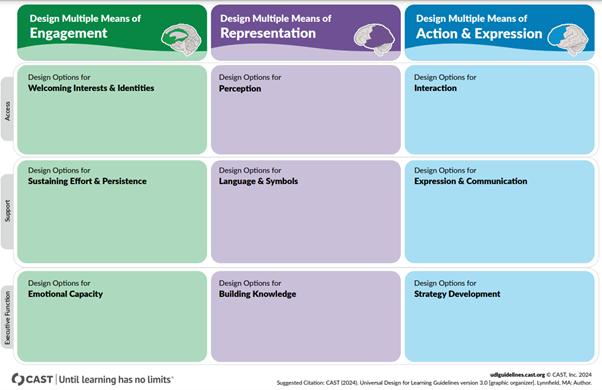

UDL is thus a framework to guide the design of learning environments that are accessible, inclusive, equitable, and challenging for every learner. Ultimately, the goal of UDL is to support learner agency: the capacity to actively participate in making choices in order to meet learning goals. UDL aims to change the design of the environment rather than to situate the problem as a perceived deficit within the learner. The table in the Figure below presents the outline of the Universal Design for Learning Guidelines 3.0.

Figure: The UDL Guidelines 3.0. (A screen-readable alternative to the above table is available on this CAST page).

The UDL Guidelines are organised both horizontally and vertically. Vertically, the Guidelines are organised according to the three principles of UDL: engagement, representation, and action and expression. The principles are broken down into Guidelines, and each of these Guidelines have corresponding considerations that provide more detailed suggestions.

The Guidelines are also organised horizontally.

- The access row includes the guidelines that suggest ways to increase access to the learning goal by designing options for: welcoming interests and identities, perception, and interaction.

- The support row includes the guidelines that suggest ways to support the learning process by designing options for: effort and persistence, language and symbols, and expression and communication.

- Finally, the executive function row includes the guidelines that suggest ways to support learners’ executive functioning by designing options for: emotional capacity, building knowledge, and strategy development (CAST 2024).

Developing inclusive education through UDL also requires attention to culturally sustaining pedagogy, which addresses the need to diversify and decolonise the curriculum, to ensure all students recognise themselves in the curriculum, and are supported to be their authentic selves and achieve to their potential.

UDL suggests that it is essential to consider how structural dynamics influence learner agency. Designing learning environments that support learner agency requires continually examining power dynamics, by challenging structures that view the educator as the sole authority and creating space for learners to make sense of content individually and collectively through interaction and reflection. Further, supporting learner agency requires recognising dimensions of culture and identity and examining where bias may be a barrier to learners being able to fully exercise their agency (CAST 2024).

Remember: Inclusion is a process. Not all of the bullet points will be relevant to our discipline, our teaching, or our student diversity characteristics. Even one small change, such as ensuring a diversity of representation in your resources, materials available 48 hours in advance, providing a glossary, or catch up materials and recordings for those who miss opportunities for social learning, can change the experience of our students. Plan for quick wins and longer term goals!

Applying Universal Design for Learning to your Teaching Practice

UDL in higher education:

A transcript of this video and more detailed information on UDL in Higher Education is available on the UDL on Campus website. Updates using the new 2024 UDL Guidelines 3.0 are expected soon.

Application of UDL to your Teaching Practice

So how can you embed UDL in your practice? Click on the headings for prompts, which have been adapted from the 2022 version to reflect the new 2024 UDL Guidelines 3.0.

Multiple Means of Representation

Learners differ in the ways they perceive and make meaning of information. We must consider how people access information, and how people, cultures, individual and collective identities and perspectives are represented within the content. Learning, and transfer of learning, occurs when multiple representations and perspectives are used. There is not one means of representation that will be optimal for every learner; providing options for representation is essential.

Key Questions

Think about how information is presented to learners. Design options that:

- Enable access to information using preferred options for perception, whether text, audio or video, and illustrated through multiple types and forms of media

- Represent a diversity of perspectives and identities in authentic ways and cultivate multiple ways of knowing and making meaning

- Cultivate understanding and respect across languages and dialects, and address biases in the use of language and symbols

- Provide options for language and symbols, clarify vocabulary, symbols, and language structures, and support decoding of text, mathematical notation, and symbols

- Connect prior knowledge to new learning and highlight and explore patterns, critical features, big ideas, and relationships

- Maximise transfer and generalisation

Reflection: Do you design for:

- Text versions of audio, through caption availability or transcripts, and vice versa, audio versions of text, through video or podcast? Options or variety in resources such as text, video, and audio?

- Variety in text, image and audio representation of perspectives and identity, acknowledging global perspectives?

- Clarity and explanation in the use of language and symbols, addressing bias?

- Outlines, maps or models illustrating relationships between prior and new learning, illustrating patterns, features or big ideas?

Multiple Means of Engagement

Learners differ markedly in what sparks their motivation and enthusiasm for learning, and how they are able to engage with learning. Learners must also be able to bring their authentic selves to the learning environment and find connections to what matters most in their lives. Learners' interests and sources of motivation may vary depending on the context, and on their sense of self, authenticity, safety and belonging. There is not one means of engagement that will be optimal for all learners in all contexts; multiple options for engagement are essential.

Key Questions

Think about how learners will engage with their learning. Design options that:

- Welcome interests and identities, by offering choice in modes of engagement, and in choice of topics or case studies, enabling autonomy, and sustaining relevance, value, and authenticity

- Nurture joy and play in learning and address biases, threats, and distractions, to enhance safety and belonging

- Sustain effort and persistence by clarifying the meaning and purpose of goals, optimising challenge and support, and offering action-oriented feedback

- Foster collaboration, interdependence, and collective learning, through a sense of belonging and community, and individual and collective reflection

- Develop emotional capacity by recognising expectations, beliefs, and motivations, developing awareness of self and others and cultivating empathy and restorative practices

Reflection: Do you design for:

- Options for topics, areas of study or module topics?

- Clarity on the authenticity and relevance of topics or areas of study?

- Options for engagement, such as synchronous (live- face to face or online) and asynchronous (completed independently)? For more information, read about the Cardiff University Blended Learning Framework .

- Variety, flexibility and options for individual and collective learning and reflection?

- Support for student development through fostering awareness and respect for diversity and variety in experiences, beliefs and motivations?

Multiple Means of Action and Expression

Learners differ in the ways they navigate a learning environment, approach the learning process, and express what they know. Therefore, it is essential to design for these varying forms of action and expression. For example, all individuals approach learning tasks very differently, and may prefer to express themselves in written text but not speech, and vice versa. It may not always be feasible to build in multiple options or choices for every activity or assessment, if a competence standard must be reached, but there should be diversity in assessment mode, as far as possible. It should also be recognised that action and expression require a great deal of strategy, practice, and organisation, and this is another area in which learners will differ. In reality, there is not one means of action and expression that will be optimal for every learner; options for action and expression are essential.

Think about how learners are expected to act and express themselves. Design options that:

- Enable variety in interactions in responses, navigation, and movement, and enable options in interactions using accessible materials and assistive and accessible technologies and tools

- Provide options and flexibility for students in the expression and communication of their learning, through multiple media and multiple tools for construction, composition, and creativity, challenging exclusionary practices

- Build fluencies with graduated support for practice and performance, addressing biases related to modes of expression and communication

- Support students in strategy development and the setting of meaningful goals, enabling students to anticipate and plan for challenges and organise information and resources

Reflection: Do you design for:

- Choice or flexibility in responses, interactions, activities and collaborations within sessions?

- A range of accessible resources, tools and technologies for expression of learning

- Choice or flexibility in the mode students can demonstrate their knowledge or skills, such as written, spoken or multi-media?

- Scaffolded support for students to demonstrate essential skills in a particular mode, for example practice runs, formative tasks and clear criteria for skills as well as content?

- Support for gaol setting, strategic planning, time-management and management of information, such as module and assessment maps, session plans and summaries of information resources?

Universal Design: Places to start:

This is an exhaustive inventory of Universal Design “places to start” in the form of a long list of Universal Design suggestions, organized according to some of the different modes of “delivery” or styles of teaching in higher education. The idea is to try any of these suggestions out in your own classroom, and see where they go.

From: Dolmage, J. T. Academic Ableism: disability and Higher Education. University of Michigan Press. https://www.fulcrum.org/concern/file_sets/j3860906x?locale=en

If you are designing Programmes, you can find out more on the Inclusive Programme Design section of the Empowering Students to Fulfil their Potential page.

Deeper Dive: Universal Design For Learning – Why Now?

In the last twenty years, there have been dramatic changes in the nature of higher education. It is not just that participation rates are higher than ever, bringing much greater diversity in the student population, but that these and other factors have altered the main mission of higher education and modes of delivery.

In the 1990s, the Higher Education participation rate was 15%, whilst now it is close to 50%, both in the UK and globally (Biggs and Tang 2011: 4). In addition, educational policy and provision has addressed inequalities through Special Educational Needs support in mainstream schools, and Widening Participation agendas in the higher education sector (Thomas and May 2010). The changing nature of employment means many more people look to retrain or study later in life, and there has been significant global movement in education, resulting in increased numbers of international students.

Higher education institutions therefore face increasingly diverse student populations with learners from different backgrounds, who have varying educational experience and academic, social, cultural and practical diversity (Jørgensen and Brogaard 2021).

Teaching substantially larger numbers of increasingly diverse students requires new approaches to the design, delivery and assessment of learning and teaching, which enable teachers to meet the needs of all students, and ensure all students have an equitable opportunity to fulfil their potential, but with realistic parameters in relation to workload and resourcing. Once embedded into design and practice, Inclusive Education and Universal Design for Learning can support these aims.

UDL Principles and Research

The UDL principles are based on the three-network model of learning that take into account the variability of all learners—including learners who were formerly relegated to ‘the margins’ of our educational systems, but now are recognised as part of the predictable spectrum of variation. These principles guide design of learning environments with a deep understanding and appreciation for individual variability (Meyer et al. 2014).

The UDL Guidelines (2024), whose foundation includes over 800 peer-reviewed research articles, provide benchmarks that guide educators in the development and implementation of the UDL curriculum. These Guidelines serve as a tool with which to critique and minimise barriers inherent in curriculum as educators aim to increase opportunities to learn (UDL on Campus 2022).

This video explains the History and Principles of Universal Design for Learning:

As with all educational models, there have been some critiques of the UDL Guidelines, and much debate around methods of implementation, in relation to the need for either comprehensive or incremental change in universities, and the viability of the guidelines for diverse student groups beyond disability. For detailed discussion and research on these and other issues, read Bracken and Novak (2019).

The latest UDL Guidelines, version 3.0, have developed the focus to address barriers rooted in biases and systems of exclusion. While the Guidelines had become a valuable tool to help practitioners design for learner variability, the updated version recognises that gaps and biases existed. Practitioners and researchers alike called for an update to make stronger connections to identity as part of variability and to address systemic bias.

Session Level: Reflect on your teaching using UDL Guidelines

Go to the detailed UDL guidelines by reading them on the CAST website and identify 2 aspects of your teaching or organisation of teaching that you would re-design to ensure you are employing universal design for learning for each of the three areas of engagement, representation, and action and expression. You may wish to click on each bullet point for ideas which might resonate for your teaching.

Focus on Assessment: Do you offer choice or variety of how students feedback on formative tasks or activities, for example orally or through text? Do you offer flexibility of roles in small group activities, for example so students take research or presentation responsibilities? Do you provide for asynchronous completion of tasks, through worksheets, mentimeter or padlet activities?

Module Level: Reflect on the organisation of your module

- Use a module map to identify the student activities for your module. Do the activities privilege certain modes, such as speech, text, or social interactions, over others? Reflect on whether you can design for multiple modes through variety in activities. Could they watch a video, instead of read? Could they work individually for some activities?

- Focus on Assessment: Are you able to offer choice in assessment mode (for example a written assignment or presentation)? Or could you offer choice in topic? Do you scaffold the skills required in seminar or workshop activities, as well as the content? Do you clarify the requirements of the assessment and the marking criteria? Could you plan for more variety next year?

Programme Level: Reflect on the student experience of your programme from a diversity perspective

- Map your programme across the three years (with weekly maps of module input and assessments, including the student activities required), and then consider the experience of the programme using student personas (see Empowering Students to Achieve their potential page). What barriers to learning or organisational challenges will particular groups of learners experience?

- Identify the opportunities provided by each module for flexibility and choice in engagement with materials and activities, representation of learning, and action and expression, and work with your module leads to co-ordinate provision.

- Focus on Assessment: consider the choice, flexibility, variety and support of assessment, from a student experience perspective. Map the assessment modes across the programme, against the weeks of study, and consider whether the mode of assessments disadvantages certain groups of students. For example, is there a weighting of written work? Also, consider the timing and bunching of assessments.

Recording of this page

References

Advance HE. 2018 Embedding equality, diversity and inclusion in the curriculum: A programme standard. Available at: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2019-09/Assessing%20EDI%20in%20the%20Curriculum%20-%20Programme%20Standard.pdf

Biggs, J., & Tang, C. 2011) Teaching for quality learning at University (4th ed.). Maidenhead, U.K.: Open University Press.

Bracken, S. and Novak, K. (Eds). 2019. Transforming higher education through universal design for learning : an international perspective. London ; New York: Routledge; Taylor & Francis

CAST 2024. Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 3.0. Online. Available at: http://udlguidelines.cast.org

CAST 2022. Key Questions to Consider When Planning Sessions. Online. Available at: https://udlguidelines.cast.org/binaries/content/assets/common/publications/articles/cast-udl-planningq-a11y.pdf

Hockings, C. 2010. Inclusive Learning and Teaching in Higher Education: A Synthesis of Research. York: Higher Education Academy.

Jørgensen, M.T.. and Brogaard, L. 2021. Using differentiated teaching to address academic diversity in higher education:Empirical evidence from two cases. Learning and Teaching Volume 14, Issue 2: 87–110

Meyer, A., Rose, D.H., & Gordon, D. 2014. Universal design for learning: Theory and Practice. Wakefield, MA: CAST Professional Publishing

Thomas, L. and May, H. 2010. Inclusive Learning and teaching in Higher education. York: HEA. Available online

UDL on Campus. 2022. About Universal Design for Learning. Online. Available at: http://udloncampus.cast.org/page/udl_about

Where Next?

The Inclusive Education CPD Offer

Toolkit

You can now go on to develop your understanding of Inclusive Education by accessing the related pages on specific topics, outlined in the map below, which relate to the Inclusive Education Framework. After accessing this page, we recommend you move to the Fostering a Sense of Belonging page.

Workshops

You can also develop your understanding of Inclusive Education by attending workshop sessions that relate to each topic. These workshops can be taken in a live face-to-face session, if you prefer social interactive learning with your peers, or can be completed asynchronously in your own time, if preferred. You can find out more information on workshops, and the link to book here.

Bespoke School Provision

We offer bespoke support for Schools on Inclusive Education, through the Education Development service. This can be useful to address specific local concerns, to upskill whole teams, or to support the programme approval and revalidation process. Please contact your School’s Education Development Team contact for more information.

You’re on page 6 of 9 Inclusivity theme pages. Explore the others here:

1.Inclusivity and the CU Inclusive Education Framework

2.Introduction to Inclusive Education

3.Fostering a sense of belonging for all students

4.Empowering students to fulfil their potential

5.Developing inclusive mindsets

6.Universal Design for Learning

8.Disability and Reasonable adjustments

Or how about another theme?

References

Advance HE. 2018 Embedding equality, diversity and inclusion in the curriculum: A programme standard. Available at: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2019-09/Assessing%20EDI%20in%20the%20Curriculum%20-%20Programme%20Standard.pdf

Biggs, J., & Tang, C. 2011) Teaching for quality learning at University (4th ed.). Maidenhead, U.K.: Open University Press.

Bracken, S. and Novak, K. (Eds). 2019. Transforming higher education through universal design for learning : an international perspective. London ; New York: Routledge; Taylor & Francis

CAST 2018. Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 2.2. Online. Available at: http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Cast 2022. Key Questions to Consider When Planning Sessions. Online. Available at: https://udlguidelines.cast.org/binaries/content/assets/common/publications/articles/cast-udl-planningq-a11y.pdf

Hainesworth, P. 2019. Inclusive Assessment: Where next? Online. Available at: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/news-and-views/inclusive-assessment-where-next [Accessed 26/9/22]

Hanesworth, P. Bracken, S. and Elkington, S. (2019) A typology for a social justice approach to assessment: learning from universal design and culturally sustaining pedagogy, Teaching in Higher Education, 24:1, 98-114, DOI: 10.1080/13562517.2018.1465405

HEA. 2012. A Marked Improvement: Transforming Assessment in Higher Education. York, HEA

Jørgensen, M.T.. and Brogaard, L. 2021. Using differentiated teaching to address academic diversity in higher education:Empirical evidence from two cases. Learning and Teaching Volume 14, Issue 2: 87–110

Meyer, A., Rose, D.H., & Gordon, D. 2014. Universal design for learning: Theory and Practice. Wakefield, MA: CAST Professional Publishing

Morris, C. Milton, E. and Goldstone, R. 2019 Case study: suggesting choice: inclusive assessment processes, Higher Education Pedagogies, 4:1, 435-447

Padden, L. and O’Neill, G. 2021. Embedding equity and inclusion in higher education assessment strategies: creating and sustaining positive change in the post-pandemic era. In: Baughan, B. 2021. Assessment and Feedback in a Post-Pandemic Era: A Time for Learning and Inclusion. Advance HE: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/assessment-and-feedback-post-pandemic-era-time-learning-and-inclusion

Thomas, L. and May, H. 2010. Inclusive Learning and teaching in Higher education. York: HEA. Available online

UDL on Campus. 2022. About Universal Design for Learning. Online. Available at: http://udloncampus.cast.org/page/udl_about

Share Your Feedback