International Students

An Inclusivity Theme Page

The changing demographic of our student population over the last 30 years has been driven by political, economic, educational, social, and technological advances. Our student and staff population offers a rich and diverse global context that enriches and brings value to our universities (Hockings 2010).

Universities UK recently suggested that:

‘International higher education and research are hugely important to our universities and to the UK’s long-term national interest. They help underpin our global reputation, influence, and impact. So, it is more important than ever that we celebrate our achievements – and work collectively to ensure that public and political support for internationalisation is sustained.

However, an increasingly challenging geopolitical context – including the long-term effects of the pandemic and the UK’s exit from the EU – has had a significant impact on universities and their global engagement. As the data shows, we are seeing changes in the composition of the international student body, while outward student mobility has suffered significantly and remains a minority experience for UK students.’

Currently a decline is being seen across the sector, changing the landscape of international education and prompting the question what are we doing for our international students?

This page focuses on the themes of transition, induction, and linguistic, cultural, and academic considerations for the internationalisation of HE. The deeper dive section explores these themes in depth, with key literature, case studies, and resources based on evidence-based research and staff and students’ perspectives.

If you don’t have time to delve into the details right now, here are top tips for teaching international students to get you started:

International students

The term ‘international students’ is usually used to describe non-UK domiciled students who have travelled to study in the UK. At Cardiff University, our international students bring new cultures, languages and traditions to our diverse and rich learning community. However, it is important to recognise the limitations of labelling students as falling within one group and of not making assumptions based on the country a student is from. All classroom environments are diverse, with home and international students enrolling with a range of ethnic, socio-economic, and religious backgrounds, prior education contexts, and ways of learning. Being an international student is just one part of a person’s multi-faceted identity.

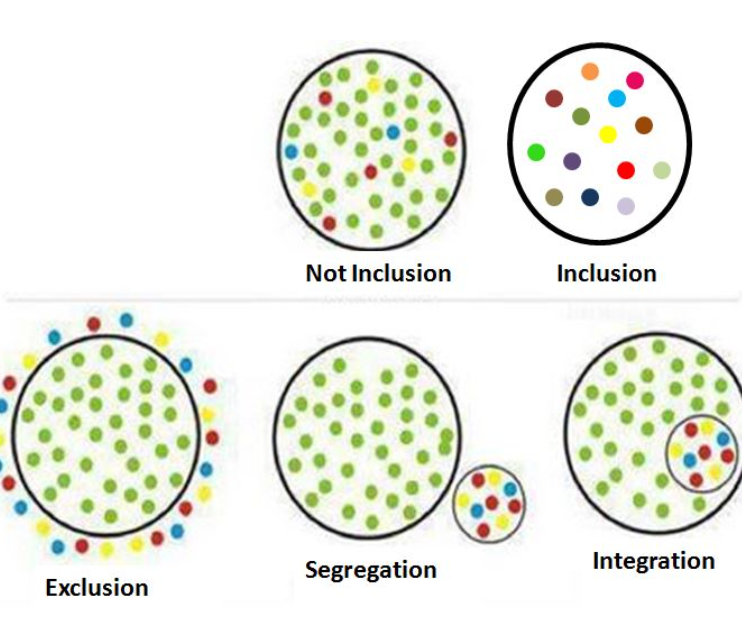

The inclusive education project takes an evidence-informed approach and understands that there is both diversity between groups of students as well as commonalities across the student body. We adopt an inclusive view of diversity (Hockings 2010) and situate our work , focusing on what international students bring to enrich our institution and learning environments. If you wish to read more about the deficit and value narrative then visit the deeper dive section.

Transition and induction

Universities offer a wide range of induction processes for students with a focus on transitioning them successfully into the new educational culture. However, when discussing transition, we do not just mean the first few weeks of university but how students navigate the student journey and transitions in, through, and out of university.

The process of transition in the broadest sense is complex and includes a huge range of stakeholders and intersectional identities. Students find the transition process challenging (Kift et al, 2010), and research suggests that for international students the process is even harder to navigate (Wu & Hammond 2011). Induction plays an important role in the success of students climatising to their new context and minimising the effects of culture shock. It can also help students form a network that becomes the basis for teamwork within the academic setting and peer support for the wider student experience. More literature and resources on the topic of induction and transition can be found in the deeper dive section click here.

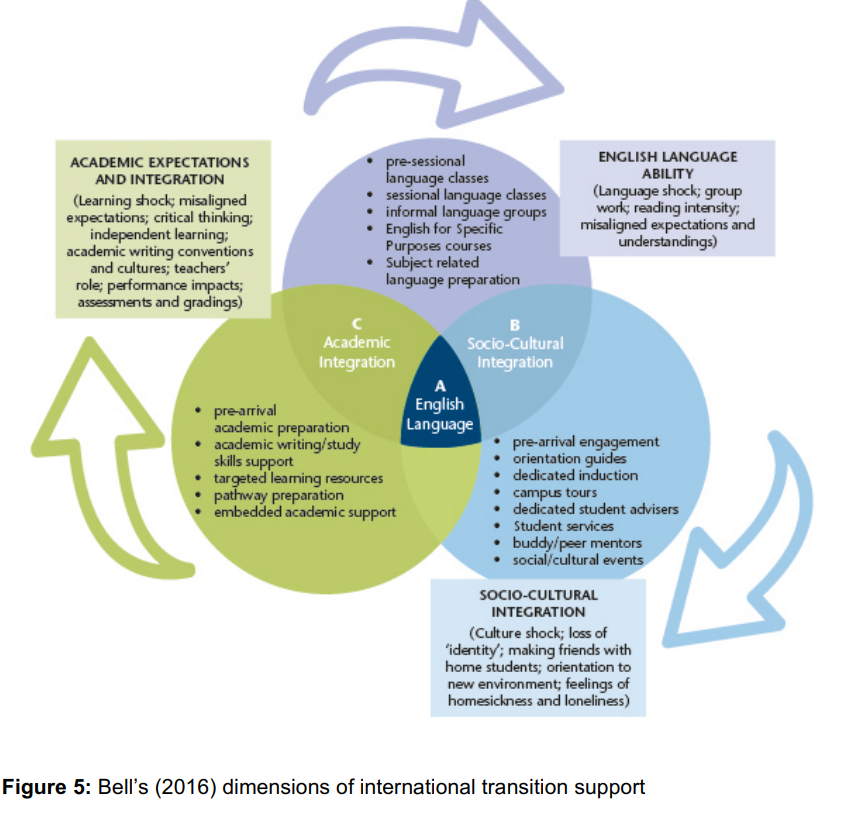

Below you will find advice based on Bell’s (2016) dimensions of the international transition support model. If you wish to delve deeper into this theme then click this link to the deeper dive section.

Academic and Cultural Considerations

Below are some top tips to get you started.

The more you find out about your students and their diverse prior experiences, cultural context, and educational background, the more you can anticipate challenges and plan for and design learning opportunities that remove these barriers. When you apply Universal Design for Learning (CAST, 2018) and culturally responsive pedagogy to your practice you are anticipating challenges and catering to a diverse student cohort designing out the barriers. It is important to acknowledge that this approach to design does not just improve the learning experience for international students it improves the learning for all students. If you would like to find out more about these pedagogical approaches, then visit our Empowering Students to fulfil their potential page. To read lecturer and student perspectives on how academic and cultural integration impacts students’ experience click on the deeper dive section here.

Linguistic Understanding

Not all international students will face a linguistic challenge, and some only to a lesser extent (Bell, 2016). However, for most international students, language proficiency is the biggest challenge when adjusting to UK university life (Sawir, 2005 and Burdett & Crossman ,2012). If you wish to find out more about how to overcome the challenge of linguistic understanding for international students then click on the deeper dive section.

Top tips:

- Ensure resources (e.g. lecture slides, readings, case studies, activity instructions) are provided 48 hours before so students can translate/ familiarise themselves.

- Plan sessions with thinking/quiet time allowing students to process the information.

- Use images and clear straightforward language.

- Write new terms or acronyms and abbreviations on the board or slides and explicitly point them out and explain them.

- Consider your pace and use of metaphors, idioms and culturally specific references, without offering explanations for their meaning.

- Explain UK-specific references to cultural or historical examples or artefacts.

Here you will find guidance to help reduce the linguistic barriers international students face:

Lectures

Provide guided questions for pre-session reading (to focus attention on key issues and give purpose to reading.

• List Intended learning outcomes and keep referring back to them to explain why they’re important.

• Use a mix of audio/visual materials and presentations.

• Build in pauses.

• Use images and speak clearly and slowly.

• Use open ended questions to help aid discussion.

• Provide opportunities for peer discussion.

• Provide pre session tasks and readings in advance, so students can prepare for the lecture content

Assessment

Discuss and analyse the rubrics/assessment criteria.

• Allow students to discuss and analyse exemplars (alongside assessment criteria)

• Offer opportunities for formative feedback early on (peer and/or lecturer feedback)

• Don’t assume everyone knows what ‘being critical’ means.

• Explain what marks mean.

• Provide assignment checklists.

• Encourage/ support reflection/ self-assessment (what went well, what can I do to improve next time)

Teamwork

There is much research on the best approach to teamwork within a multicultural setting. The approach you take will depend on your students and the discipline but it should:

- Discuss the benefits of working with others, raising the issue of cultural differences and potential misunderstandings with students before the activity.

- Set ground rules (co-created with students), different roles, expectations, and what success looks like.

- Support groups to come to a common agreement as to how they will handle contentious issues that may arise.

- Assign groups to help promote social cohesiveness between cultures (Burns,V 2013) and avoid students selecting to work in mono-cultural groups

Seminars

- Explain what seminars are for and what you expect from the students.

• Provide pre-seminar preparation tasks.

• Find resources/ examples from students' contexts.

• Tap into students’ expertise and provide opportunities for students to share from their context (but don’t force them).

• Allow for thinking time before expecting an answer and allow students to finish.

• Get students to share their thoughts/ ideas with each other before reporting back to the whole class (creates a safe space to share).

Contentious issues

Focus on an exploratory model of discussion- seeking information to gain a new perspective.

• Anticipate material that could be controversial and actively plan to manage it.

• Model behaviours of responding using neutral statements.

• Be explicit about the value of knowing what you don’t know.

• Use open questions to navigate the discussion.

Recording of the page

International students: The deficit narrative

The deficit narrative is widely used, and sees teachers and educationalists focus on the ‘lack’ of language, understanding, and integration, rather than how international students enrich the learning experience for all. A number of researchers have explored this phenomenon:

- A lack of language and academic skills (Lower 2017)

• A lack of social integration (Cockrill 2017)

• A lack of confidence to engage with learning and questioning opportunities (Turner 2015)

• A lack of critical thinking skills or ability to participate verbally (Marline 2009)

• A lack of knowledge of local issues and institutions (Krall 2017)

The deficit narrative is rooted in stereotypes of one type of international student but applied to all. It is this ‘lack of’ narrative that can foster the presence of intercultural tensions between home students and create the feeling of ‘other’ shaping both learning relationships and pedagogical practices. (Straker 2015). Many international students perceive discriminatory language and bias from their classmates (Heloitt et al 2020), some of which implies that international students need to assimilate into traditional UK pedagogical practices. This gives the perception to international students that it is their job to adjust and assimilate to ‘our way’.

The Advance HE (2024) ‘Internationalising HE Framework’ highlights the responsibility of the university to support students with the challenges they face.

When a deficit narrative is applied there is also a missed opportunity to recognise and optimise the diverse cultural, intellectual, and experiential perspectives that international students can offer to all student's experiences.

International students: The value narrative

Recent literature acknowledges how individual agency and adaptability are important to understanding how students learn, alongside the varying dimensions of diversity and traditional stereotypes and assumptions of certain groups of students (Sanger & Gleason, 2020). Lomer (2017) applies a value narrative that situates international students as offering a window into the world, enhancing higher education quality by facilitating internationalisation. International students offer a different perspective and, when valued, can enhance the learning experience for all students, gaining cultural competencies that will prepare all for the globalised world. There are several benefits for all students when the learning environment recognises, celebrates, and values the diversity of everyone.

Cultural enrichment

An international cohort brings an array of cultures, perspectives, and experiences to the academic environment.

Global networking

Interacting with peers from around the world provides students with a valuable opportunity to build an international network. This network can extend beyond the academic setting and contribute to future collaborations and professional/ personal connections.

Enhanced Learning Experience

Exposure to different perspectives challenges traditional viewpoints and cultivates critical thinking. This diversity can lead to more comprehensive discussions and a deeper understanding of global issues.

Preparation for Global Careers

Engaging with an international cohort prepares students for global workplaces. The ability to work effectively in diverse teams is a sought- after skill in today's interconnected world.

Thus, situating our thinking using the value narrative ensures we reflect on and consider the needs of all the students to enhance the learning environment for all.

Transition and induction

Transitions can happen throughout the student journey and when successful can lead to the development of identities and new ways of knowing (Beach 1999, in Ecohard and Fotheringham 2017:101). Ploner (2018) discusses academic hospitality which focuses on the reciprocal exchange between ‘host’ and ‘guest’. When you apply this concept to international students you are reframing the deficit narrative and moving towards the notion of actively valuing and learning from different cultures.

Students entering university will have mixed experiences and expectations. International students traveling to study have already demonstrated a commitment to studying in another country. However, the reality can be very different from the expectation. For a home student, the process of entering a new context can be challenging in many ways. The additional dimensions of acculturation and adjustment within the process of transition create an extra challenge for international students. These need to be considered when planning induction and transition processes. Bridging the gap between prior experience and expectations to ensure that all students can perform to their potential does not mean changing what we ask of students, but it does mean recognising the scale of the transition for some students (Scudamore 2013).

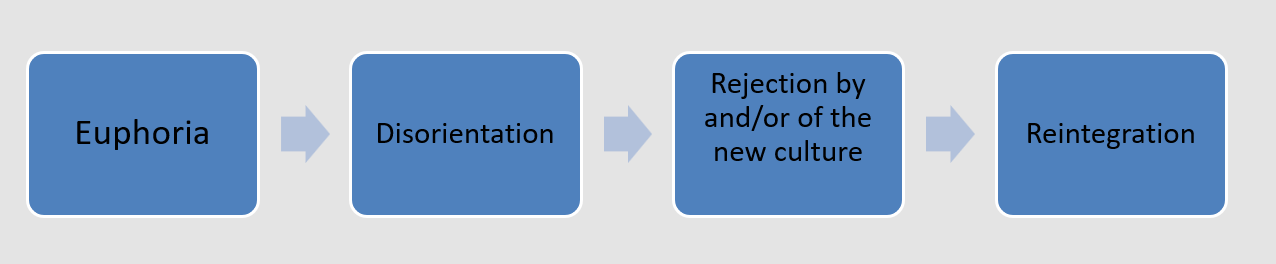

Scudamore (2013: 10) identifies several phases to transition that can last over a few months, some or all might be experiences by students:

Figure: Stages of transition (Scudamore 2013 p10)

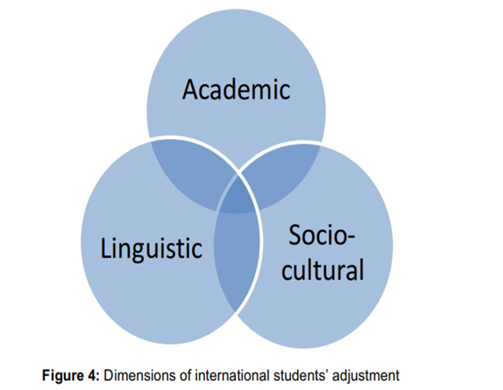

Dimensions of adjustment

Broadly the literature presents 3 dimensions of adjustment for international students

Here is an example of some challenges international students may face when adjusting to university:

| Academic | Linguistic | Sociocultural |

| Teaching practices | Communicating with native speakers (speed, accent, register, body language and colloquialism etc) | Navigate new city, work out public transport, find accommodation |

| Classroom dynamics | A mismatch between standardised proficiency tests and reality | Make new circle of friends |

| Core traditions of L&T (e.g. student centred learning) | Understanding and producing academic texts | Join healthcare system |

| Core values (e.g. concepts of success) | Adapt to food, weather, social conventions | |

| Assignments and assessment methods | Deal with financial pressures |

Dimensions of international support model (Bell 2016)

The following resource shows Bell’s (2016) dimensions of international support model’ highlighting the type of support universities offer, and identifying key practices to help support the transition process.

EAP tutor 1

I was wondering how the university currently considers international students in our equality and diversity efforts. This is prompted by discussions with some international students about how much they struggled with classes where e.g. the lecturer uses very complex language that home students understand but international students do not, and the emotional impact of feeling sidelined in classes.

It's perhaps inevitable there would be some challenges in this area, and some would argue that it is the responsibility of students to ensure they have the language abilities to study in the UK. However, these are students who have met the language standards required by the university but find that this isn't sufficient for the level of language used by some lecturers. This isn't about 'dumbing down' content - but rather thinking about the type of language used (e.g. long complex sentences, lots of idioms, cultural references that are known only to home students).

EAP tutor 2

International students often seem aware of the need to do something ‘critical’ in their writing but ask questions about what exactly this means in practice. Looking up the word ‘critical’ in a dictionary may add to the uncertainty. In their essay questions, lecturers can use different words and phrases to ask for a critical approach. A few of these that come to mind are:

o Evaluate

o Critically evaluate

o Assess

o Build an argument

o Show your stance/position/perspective/motivation

And sometimes, just the word ‘discuss’ might be used (maybe with the ‘critical’ input assumed)

Examples of what counts as ‘critical’ in a specific context/question are difficult (and risky) for a writing support tutor to give.

EAP tutor 3

International students often talk about the difficulty of participating in discussions with home students. Sometimes they struggle to understand – particularly more colloquial English – but also to be understood. One student recently told me that that she feels home students avoid talking to her as she thinks she makes them feel uncomfortable if they struggle with her accent. I feel there is a quite urgent need for academic staff to engage home students as well as international students in developing an inclusive classroom - and indeed an inclusive programme and School environment. This needs to happen from day 1. Or even before. To what extent do our home students understand what it means to study at an international university - if indeed we are one?

Many international students also comment that by the time they have formulated something to contribute to the discussion, the home students have moved on to another aspect of the topic. This to me suggests a greater need for the scaffolding of discussion activities – for example, the need to build in thinking and preparation time but also more private (e.g. pair) rehearsal before larger group discussion.

Lecturer 1

International students often have difficulty understanding what the marking criteria mean in a real sense. For example, the criteria may include quite generic ideas like 'written work has to be well-referenced, well-structured and show evidence of evaluation' but those skills are difficult to demonstrate if they aren't properly explained. Similarly, feedback on formative work has to be explained in quite a lot of detail so it's clear what needs to be changed.

Lecturer 2

In many countries, students are used to a system where it's possible (and typical) to get very high percentages on coursework and in exams (e.g. 90-100%). They are often shocked when they get a grade here around 60% and are told that it's 'good'. They often panic that they're failing and worry about telling their parents. Explaining the grading system here and that 60-70%+ constitutes a good/very good grade is advisable.

Linguistic understanding

As mentioned above linguistic proficiency plays a fundamental role in students’ ability to fully integrate into their new context. Below you will find a selection of international students' perspectives on linguistic considerations from Jenkins and Wingate (2015).

Student 1

IELTS is about giving your opinion, like you have a topic and you write an introduction, a body and a conclusion, and you come up with your ideas and that’s fine. And then you think you should do the same in your university essays.

Student 2

The assignments they gave us were always for evaluation, for marking. But they might give us different types of assignments, just to give feedback.

Student 3

But the problem is the time […] and I don´t look at it [i.e. grammar problems] as something that I really need to improve because I´ve got other priorities, I need to submit coursework, I need to do my assignment, so that problem doesn´t get resolved.

Student 4

If you are disabled they give you some allowances, they give you some empathy, they give you some you know credits [...]. If you are dyslexic they give you some, they give you some exemption as well, right? When you´re a foreign student you almost like a dyslexic person, I mean, not literally the same but you´re almost fulfilling the disabled criteria […] so what I would suggest is if universities look at the point these people are making […] and the ideas and the knowledge that the foreign students have got to impart or put, that should be marked in terms of criteria.

Key research on the role of linguistic proficiency and the challenges international students face, (Gatwiri G. 2015):

• There is a discourse about whether traditional standardised language tests and grammar methods inadequately prepare students (Wu and Hammond 2011). Even when students’ English language skills are good when they arrive at university, they find that their linguistic proficiency is insufficient to cope with the demands of an English-speaking environment.

• Challenges also lie in the subtleties embraced by academic writing. The level of language competence to identify these differences and model them in their writing can be demanding.

• Reviewing sources for reliability and validity and the language used and context can be less accessible to students creating barriers for those students who are not English first language speakers. (Ramachandran 2011: Ecohard and Fatheringham 2017).

It is not just the academic language proficiencies that can cause a challenge but the communication with native speakers and the pace of the speaker, dialect, accent, and use of idioms and metaphors that are culturally dependent can create a sense of isolation that can impact both academic and socio-cultural integration. (Wu and Hammad 2011, Akanwa 2015).

Considerations need to be made about:

• How English was taught in the home country and to what level of acquisition, the application of informal English in the UK, the use of idioms, metaphors, and culturally specific references, and lastly the specific academic language associated with the discipline.

• Whether the student has learned English from a native English speaker or someone who has English as an additional language (Ramachandran 2011).

Many nuanced factors contribute to how a student acquires language and it would be unrealistic to expect international students to arrive in the UK using fluent English, and a knowledge of contextual references, metaphors, and idioms to communicate effectively (Echochard and Fotheringham 2017).

This view undermines the complex nature of applied linguistics and acquiring another language. Many international students choose to study in the UK as they understand the value of immersing themselves in the language to improve their linguistic ability. Therefore, it is important to acknowledge the challenge of linguistic proficiency and be mindful of its impact on the learning environment

Signpost support

Academic English Skills for International Students

English Language Programmes’ Academic English Skills team provide free classes and one-to-one tutorials to current international students whose first language is not English. We can support you with advice on the skills you need for academic study in the UK.

Classes and workshops

One-to-one tutorials

Self-study resources

Further information and enrolment

Contact

If you have any further questions, please contact:

Academic English Skills for International Students

academicenglish@cardiff.ac.uk

https://www.cardiff.ac.uk/study/international/english-language-programmes/academic-english-skills-for-international-students

Practical Considerations

Assumptions: They will have all done well in their educational system, however, they will not all share the same knowledge and skills and may have different life experiences to your own. Do not necessarily expect them to understand all the academic conventions you may take for granted, or know how to prepare for a seminar or case study.

Reflection Questions:

• What assumptions are you making about the knowledge of your students?

• What are you expecting that they can, and cannot do?

• What expectations do you have of your students?

Manage expectations: Where possible, through websites, pre-arrival documentation, email briefing, the VLE and induction week; help students to understand what to expect from your course or module and also what you expect of them.

Reflection Questions:

• What will be the class size?

• How will the module be assessed?

• How many lectures will there be?

• What formative tests are there?

• How much reading do you expect them to do each week?

• What is the structure of the module and what topics will be covered?

Presentation style: Use a slow and clear voice, allow students the chance to familiarise themselves with your use of language and accent. use of metaphors, idioms, be clear!!

Reflection Questions:

• Do you have specific phrases you use that could be confusing?

• What specific academic phrases, vocabulary will they need to know?

• How fast do you talk, volume, direction you face?

Encourage speaking in class: The way you receive the first few class contributions is very important for the class dynamics as the module develops. Welcome all contributions and try not to be critical of any comments made (see Buttner 2004). If a student has misunderstood the point, thank them for their contribution and try to encourage another student to offer an alternative point of view. Be explicit about encouraging all contributions and remind students that obtaining a range of viewpoints is helpful to them because they need to understand there are always arguments for and against different approaches. Students who are reluctant to give their views might be prepared to feedback on an idea that they have talked about with peers.

Reflection Questions:

• Thank you for that viewpoint, does anyone have an alternative?

• I like what you said, can anyone expand on this?

• Is there an alternative viewpoint?

Representation: Wherever possible, use cases with a multi-national context that do not favour the contextual knowledge of the home students. Alternatively, use a case that forces home students to seek contextual understanding from international students.

Reflection Questions:

• Is the module/program representative of my students?

• Who ‘s voice is missing? What does that tell us?

• How can you give space to discussion and critiquing discipline context?

Resources

UKCISA - Discussing difference, discovering similarities:Toolkit for academic staff to improve interaction and cross-cultural learning between students from different cultural backgrounds.

https://s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/assets.creode.advancehe-document-manager/documents/hea/private/resources/language_1568037225.pdf : practical tips on language for international students

How can universities help international students feel at home? | Student experience | The Guardian : Examples of good practice in other universities.

Teaching International Students | Center for Teaching | Vanderbilt University: practical advice on supporting international students

7_steps_to_Internationalisation_2012.pdf (plymouth.ac.uk): internationalising Teaching and Learning

Podcasts:

https://www.timeshighereducation.com/campus/podcast-rethinking-internationalisation-higher-education

https://shows.acast.com/63030887e182680013984f2f/65bc17088c97ea0017a58214

References

Burns, V. (2013) Developing skills for successful international groupwork. AdvanceHE. Available at: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/developing-skills-successful-international-groupwork

Ecochard, S. and Fotheringham, J. (2017). International students’ unique challenges – Why understanding international transitions to Higher Education matters. Journal of Perspectives in Applied Academic Practice, 5:2, 100-108

Gatwiri, G. 2015. The Influence of Language Difficulties on the Wellbeing of International Students: An Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis. Inquiries Journal/Student Pulse [Online], 7. Available: http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/a?id=1042

Héliot, Y., Mittelmeier, J. and Rienties, B. (2020). Developing learning relationships in intercultural and multi-disciplinary environments: a mixed method investigation of management students’ experiences. Studies in Higher Education, 45: 11

Hockings, C. (2010). Inclusive learning and teaching in higher education: a synthesis of research. AdvanceHE. Available at:

https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/inclusive-learning-and-teaching-higher-education-synthesis-research

Jenkins, J. and Wingate, U. (2015). Staff and students’ perceptions of English language policies and practices in ‘International’ Universities: A case study from the UK. Higher Education Review, 47:2, 47-73

Lomer, S. and Mittelmeier, J. (2023). Mapping the research on pedagogies with international students in the UK: a systematic literature review. Teaching in Higher Education, 28:6, 1243-1263,

Lomer, S., Mittelmeier, J. and Carmichael-Murphy, P. (2021). Cash cows or pedagogic partners? Mapping pedagogic practices for and with international students. Society for Research into Higher Education (Research Report). University of Manchester.

Lomer, S. (2017). Recruiting International Students in Higher Education Representations and Rationales in British Policy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

Marlina, R. (2009). ‘I Don’t Talk or I Decide Not to Talk? Is It My Culture?’- International students’ experiences of tutorial participation. International Journal of Educational Research 48:4, 235–44.

Newsome, L. and Cooper, P. (2016). International students’ cultural and social experiences in a British university: “Such a hard life [it] is here”. Journal of International Students, 6:1, 195-215

Rhoden, M. (2019). Internationalisation and intercultural engagement in UK Higher Education – Revisiting a contested terrain. In International Research and Researchers Network Event. Society for Research in Higher Education.

Scudamore, R. (2013) Engaging home and international students: A guide for new lecturers. The Higher Education Academy.

Straker, J. (2016) International student participation in Higher Education: Changing the focus from “International Students” to “Participation”. Journal of Studies in International Education, 20(4), 299-318.

Universities UK (2023) International facts and Figures 2023. Available at: https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/universities-uk-international/insights-and-publications/uuki-publications/international-facts-and-figures-2023

Share Your Feedback

Recording of Deeper Dives

Where Next?

The Inclusive Education CPD Offer

Toolkit

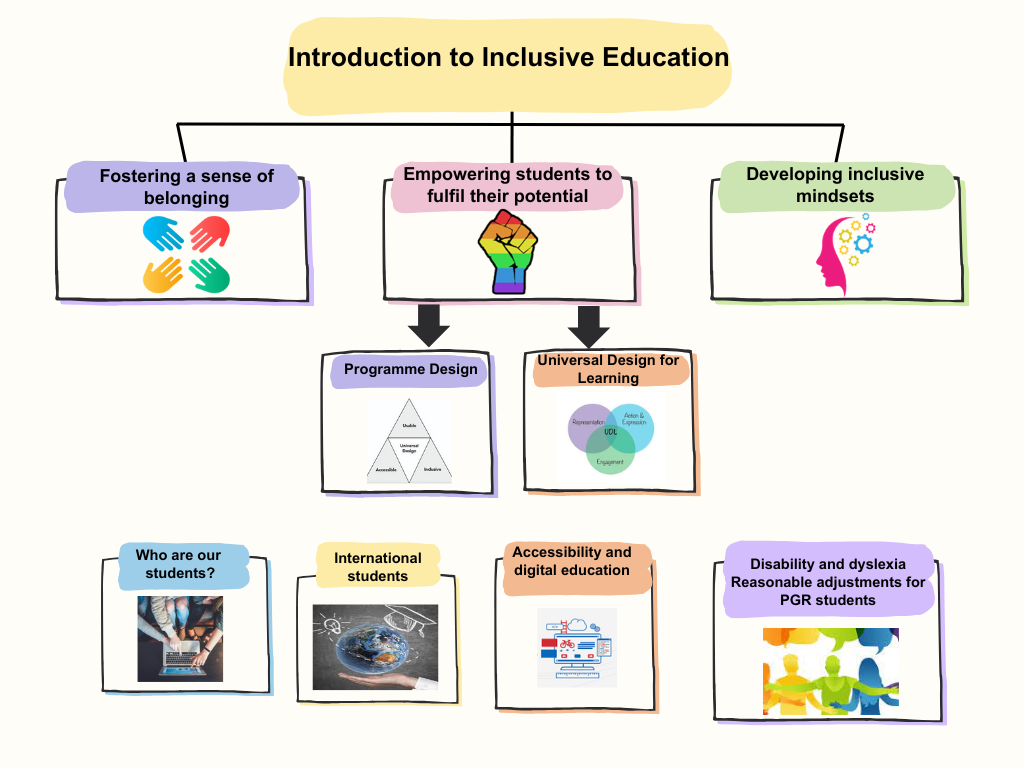

You can now develop your understanding of Inclusive Education by accessing any of the related pages on specific topics, outlined in the map below, which relate to the Inclusive Education Framework. You can jump to any useful topic, as you require.

Workshops

You can also develop your understanding of Inclusive Education by attending workshop sessions that relate to each topic. These workshops can be taken in a live face-to-face session, if you prefer social interactive learning, or can be completed asynchronously in your own time, if preferred. You can find out more information on workshops, and the link to book here.

Bespoke School Provision

We offer support for Schools on Inclusive Education, through the Education Development service. This can be useful to address specific local concerns, to upskill whole teams, or to support the programme approval and revalidation process. Please contact your School’s Education Development Team contact for more information.

Map of Topics

Below is a map of the toolkit and workshop topics, to aid your navigation. These will be developed and added to in future iterations of this toolkit:

You’re on page 9 of 9 Inclusivity theme pages. Explore the others here:

1.Inclusivity and the CU Inclusive Education Framework

2.Introduction to Inclusive Education

3.Fostering a sense of belonging for all students

4.Empowering students to fulfil their potential

5.Developing inclusive mindsets

6.Universal Design for Learning

8.Disability and Reasonable adjustments

Or how about another theme?