Feedback

Getting Started

Academic Feedback is defined as ‘a process through which learners make sense of information from various sources and use it to enhance their work or learning strategies’ (Carless & Boud, 2018).

This page has been divided into four sections, where staff will find useful links, tips, reflections, and exemplars from peers in four main areas focussed on the enhancement of academic feedback practice at Cardiff University:

1. The information about academic feedback provided to our students;

2. What students need to know about academic feedback and how to use it;

3. The nature and tone of the academic feedback that students receive, and;

4. How students are supported to use their academic feedback effectively.

As you work your way through this page, please also refer to the following resources:

- The Cardiff University Academic Feedback Policy

- The Cardiff University Strategic Approach to the Enhancement of Assessment and Feedback for 2023-2027

- The Deeper Dive section for further reading, and a Board of Studies Feedback Strategy Template.

The information about academic feedback provided to our students

All students will be provided with information at the start of the academic year about the academic feedback they will receive. This information will set out what, when, and how students will receive academic feedback, both that provided on summative assessments, and that provided to students on an ongoing basis, e.g. through tutorials, from supervisors, on formative assessments etc.

What?

As a minimum, it is recommended that students be provided with the below information for each assessment task.

- The name of and a brief description of the assessment

- The percentage contribution (where applicable) of the task to the module’s outcome

- The format(s) to be used for the submission of the assessment

- Whether it is a summative and/or formative task and what the pass mark is

- The duration of the assessment and/or its length / volume (if applicable)

- The assessment criteria

- The assessment release date

- The deadline date for submission

- The deadline date for feedback comments return

- What feedback follow-up opportunities exist

As well as providing this information for students (and highlighting to them when it is available, where it is located, and how it can be used) it is good practice to support and follow this up through in-class discussion. Talking with your students about academic feedback presents an opportunity for you to make students better aware of the responsibilities they have to utilise feedback to improve their learning.

It is also important for Schools to provide information to students on the format of academic feedback, any differences between the academic feedback to be provided on formative and summative assessments, and any opportunities for additional academic feedback (e.g. through the Personal Tutor system).

When?

Information about academic feedback will be provided to students at the start of each academic year, preferably during Welcome Week briefings.

How?

It must be made clear to students where (Learning Central, Student Handbook etc.) information about academic feedback can be found, and whether additional support will be available.

What students need to know about academic feedback and how to use it

It can be frustrating for staff to find many students who do not appear to utilise feedback comments effectively. Equally, it can be exasperating for students to receive comments they find unclear and that do not help them identify how they can improve. These difficulties, together with many of the other issues and problems with academic feedback, largely come from a feedback model based on a one-way transmission of information from staff to students. This is no longer considered to be an effective model.

For the comments that are provided to students on assessments to be effective, feedback needs to be a ‘dialogic process’. Thus, it can be argued that such comments do not become feedback until they are used by students to help improve their learning. In this way we are moving towards a new (more effective) paradigm of feedback, seeing feedback as process and not as a product (Boud and Molloy, 2013).

Research has also identified that part of this ‘process’ involves the development of feedback literacy in both staff and students.

“Feedback literacy denotes the understandings, capacities and dispositions needed to make sense of information and use it to enhance work or learning strategies” (Winstone and Carless, 2018).

Feedback literacy has been identified as having the below four dimensions (adapted from Carless and Boud, 2018):

The ability to …

Recognise and appreciate feedback

Do your students recognise all of the different ways in which they can receive feedback? Do they know what to do with the feedback they receive? If they don’t, you might look to use one of the below short ‘interventions’.

| Give students an example of the feedback you provided last year – and either explain or identify how students could use this … then ask students to work in small groups and post (via Mentimeter) how they would use the feedback, discussing their responses. |

| Ask students to post (via Mentimeter) some examples of the feedback they have already received (particularly useful in disciplines where students often receive ongoing oral feedback – e.g. in labs, in problem solving tutorials, from placement and/or other clinically focused colleagues). |

| Ask students to post (via Mentimeter) their own definitions of what feedback means, and then discuss and deconstruct their responses to help them understand that e.g. marks are not feedback, that comments only become feedback when they are acted upon etc. |

Manage its affect

Receiving feedback can evoke a variety of emotions that may interact with cognitive engagement and hence the ability of our students to use feedback to learn. Hence, you might wish to:

| Get students to discuss the feedback they have received in pairs and ask each pair to discuss the following questions: How did negative comments make them feel? How can they turn negative comments around and use them to improve? Why it is important for feedback to include negative comments? |

| Direct students to available sources of information, support and advice, should you feel that feedback poses wellbeing risks. |

| Ensure that feedback comments (especially to early year students where confidence can be fragile) balance constructive criticism, positive comments and directions to improve. |

| Give students ‘permission to fail’, by ensuring initial developmental tasks carry little (if any) weight to module outcomes. |

Take action

Although you cannot force students to use feedback comments, you can support them to make better use of these comments, and prompt and encourage them to take action, by adopting one of the below exercises.

| Give students an example of the feedback you provided last year – and either explain or identify how students could use this … by asking students to work in small groups and post (via Mentimeter) how they would use this and then discussing their responses. |

| By including links to useful online resources in the feedback you give – directing students to utilise these. |

| By ensuring that feedback can effectively feedforward to the next task – e.g. by asking students to set out how they have used previous feedback on the coversheet of their next assignment, or by awarding marks for comments that explain how they have used previous feedback. |

| By allowing students to get and use feedback on drafts prior to the final submission of that assignment. |

Make evaluative judgements

“Evaluative judgement is the capability to make decisions about the quality of work of self and others” (Tai, 2018).

| By providing students with exemplars alongside the agreed assessment criteria and getting the students (in small groups) to grade the exemplars, applying the agreed assessment criteria. By then discussing the different marks and responses (making students more aware of the complexity involved in grading work and providing feedback) (Peer assessment). |

| By asking students to self-assess their own work against the agreed criteria, submitting a cover sheet that includes their own predicted mark against the criteria. To then provide the students with some feedback that comments on their marking, helping to hone their evaluative judgement (Self-assessment). |

| By getting students to work with a peer’s assessment prior to its submission, providing feedback on work-in-progress against grading criteria. (Note: Peer review is most effective when it focuses on criteria that peers are best equipped to comment, such as clarity of communication or strength of argument etc.) (Peer assessment). |

| By helping students to better understand assessment criteria by using the generic criteria to develop suggested assignment-specific criteria. By then asking students to work in groups and discussing the meaning of criteria and articulating the distinguishing features of work at each level. |

You should not expect academic feedback literacy to happen overnight.

If you only do one quick thing… read through the feedback you have provided on a sample recent assessment and consider it from the student perspective. How would this feedback make you feel? Would you have a clear idea of the action you could take to improve your work in future assessments?

The nature and tone of the academic feedback that students receive

This section of the toolkit is concerned with the nature of the comments provided to students as feedback. Whilst without further help and support some students may not utilise these comments, it is nevertheless cucial to ensure that our comments are framed in ways that more students will find useful.

Following the ‘7 hallmarks of effective feedback’ (Wiggins, 2012) will help ensure that your comments are appropriate and usable. These are set out and explained below.

Goal-oriented

Academic feedback comments often carry more weight and meaning when they relate both to the learning outcomes and the assessment criteria for that task. While many students find comments useful that are tied and clearly relate to specific parts of the student’s work, it is also useful to summarise these comments in a short summary (often provided at the end of the student’s work) that identifies the key areas that can be improved and the resources that can be used to achieve this.

| Examples of effective practice:

WELSH: Seeking to provide students with 'less feedback and more targeted...short summary paragraph with 3 targets'. SOCSI: 'asking students what they want to work towards - co-creation of aims' |

Focused on key points

Feedback should be concise and focused on two or three points, covering areas of strength and growth, as well as areas to improve. Concise, feedback is easier for students to understand and will be more likely acted upon. All should try and ensure that the volume of feedback provided to different students is pretty consistent.

Actionable

As well as including links to any resources that students should use to follow up on feedback comments, staff should discuss with students how you expect them to action and utilise their feedback. Where assessments are designed to support and follow on from each other, staff should use feedback to signal to students what you would like to see ‘next time’. A number of colleagues also use a coversheet on which students are asked to identify the area(s) on which feedback comments will be valuable (elective feedback).

Student-friendly

Academic feedback comments are best personalised (using first- or second-person language) to help students engage with these. Comments should be critical but constructive, and where possible should adopt a positive and encouraging tone. Whilst comments will be better understood when they use clear and simple language, staff should also provide students with further information about any opportunities created to follow up on comments.

| Examples of effective practice:

PHYSX: weekly group tutorials prior and following the assessment. Exemplars, use of peer marking. SHARE: personal tutor system – students often don’t need help understanding feedback, others do need help understanding terminology used. GEOPL: short video (Cardiff University login required), put together by Dr Neil Harris, for advice on the ‘phrasing and expression of feedback’ comments. |

On-going

To be effective, feedback must also be ongoing, consistent, and timely. This means that students need ample opportunities to use feedback and that feedback must be accurate, trustworthy and stable. When feedback isn’t timely, students are disengaged and demotivated. Teachers are responsible for building in regular feedback loops into their practice. Graders are responsible for meeting all deadlines and delivering consistent, calibrated feedback.

Encourage continuous feedback discussions and opportunities to develop feedback literacy and impact.

Consistent

Follow set standards, provide trustworthy, fair, and accurate feedback.

| Examples of effective practice:

ARCHI: ‘submissions map showing each module, which identifies whether feedback will be formative/summative, oral/written, where it will be provided etc.’ |

Timely

Ensure agreed timelines are met, building trust and the reliability of the feedback process.

If you only do one quick thing… ask students to look through the feedback that they have received on a recent assessment. Can they identify links between the feedback they received and the module / programme learning outcomes?

Cohort level feedback

Advantages of cohort level feedback

• Suited to more ‘objective’ assessments e.g. MCQs, where there may be common errors

• Particularly helpful when teaching large groups, where giving meaningful, actionable individual feedback is very time-consuming

• Can provide students with more timely academic feedback

• Can be tailored to each cohort, but also be informed by previous, and inform future cohort academic feedback (where future cohorts may be given a previous cohort’s academic feedback in advance of an assessment)

• Can complement and contextualise individual feedback by giving students an awareness of common areas of weakness, and examples of successful performance

Considerations in giving cohort level feedback

- Provide a statistical profile so that students can see where they sit in comparison to others

- Comment on what the achievement of a first looked like – what did the highest-achieving students do well?

| e.g. ‘The best answers synthesised several sources in constructing an argument, addressed potential counter arguments, and utilised case studies.’ |

- Comment on the fails – where did the students who failed go wrong?

| e.g. ‘Fails occurred where answers were too short, or where arguments were unsupported by appropriate sources.’ |

- Comment on common significant omissions.

| e.g. ‘Many students did not refer to high rates of infant mortality in the period...’ |

- Comment on how well students utilised module material – lecture content and key texts.

| e.g. ‘The issue of educational reform was referred to in the first lecture, but many students failed to address this in their responses.’ |

- Comment on task response – were the questions answered well?

| e.g. ‘A number of students missed the main factor needing to be addressed, namely...’ |

- Feedforward – how can this academic feedback be used to improve performance in summative and other future assessments?

| e.g. ‘Defining key terms as part of the introduction to the essay will provide clarity in future essay assessments.’ |

- Consider including a number of quotes, or examples (with permission) from individual scripts that achieved the highest marks.

How to communicate cohort level feedback

- Post in Blackboard Ultra (students may not engage)

- Go through it in a module session post assessment (more effective?)

- Provide it to the next cohort before their assessment (potentially very effective)

- Create a feedback bank for individual assessments (useful and time-saving)

Peer Feedback

Engaging students in peer academic feedback fosters a collaborative and interactive learning environment, enhancing teaching and learning practice. Please see the page on Assessment and Feedback Literacy for more ideas on peer feedback. Students should be informed about any intended use of peer feedback, or the use of BuddyCheck for assessments that rely on Teamwork.

How students are supported to use their academic feedback effectively

There are a number of ways in which students can be supported to use their academic feedback effectively.

Using Blackboard Ultra feedback tools

It is important to consider the format of the feedback you give. Feedback may be written, audio, or video, or a combination of types. The format may reflect student or staff preference, the type of feedback most suited to the module or discipline, and considerations of inclusivity.

Written

• Text feedback, such as QuickMarks

• Margin comments

• Written summary feedback

• Auto quiz feedback

Audio / video

• Audio feedback in Turnitin

• Blackboard Ultra audio & video feedback

• Face-to-face meeting

A recent systematic review of 58 studies on video feedback showed it to be: “more detailed, clearer, and richer quality” that led to “increased understanding and higher order thinking skills, more personal, authentic and supportive communication” (Bahula and Kay, 2021). Crucially, using audio and video to generate feedback comments can also save staff time, so it is worth investing some time to learn how to do it.

Different methods of feedback can be used in isolation or combined with one another to provide richer feedback to the student.

In this short video, Dr Jonathan Kirkup, lecturer in Politics, talks about his experience of using audio feedback.

Watch this short video with guidance on using Blackboard Ultra to give feedback in a variety of formats, including written, audio, and video feedback.

Co-design Approaches to Assessment and feedback with your Students

Agreeing an approach to academic feedback with your students at the start of an individual module can have a positive impact in a number of different ways. For example, introducing formative assessments that are awarded a mark, and are clearly linked to summative assessment performance can reduce your marking load. It can also allow you to focus on feed-forward comments on these formative tasks and students can be involved in peer feedback at this stage. There is more value to these feed-forward comments than to comments at the end of a module that are unlikely to be used by students.

If you only do one quick thing… start a conversation with colleagues about their experiences of giving audio or video feedback if you’ve never tried this.

Helping Students to Become Feedback Literate

To use feedback comments effectively, students need to know what these comments are actually telling them, where they are placing them, and how they should utilise them. Feedback literacy does not happen overnight but is the foundation that supports students to use feedback comments effectively. Online information on a range of practical short initiatives that you can use to support student assessment and feedback literacy can be accessed here.

You may also wish to consider how students themselves can generate inner feedback (Nicol, 2022) or how practical reflective cover sheets may also help (see the Deeper Dive section for more information.)

Deeper Dive

Board of Studies Feedback Strategy Template

Please see the Board of Studies Feedback Strategy Template here.

Inner Feedback

A useful resource for helping students to develop academic feedback literacy is Nicol (2022)’s Active Feedback Toolkit.

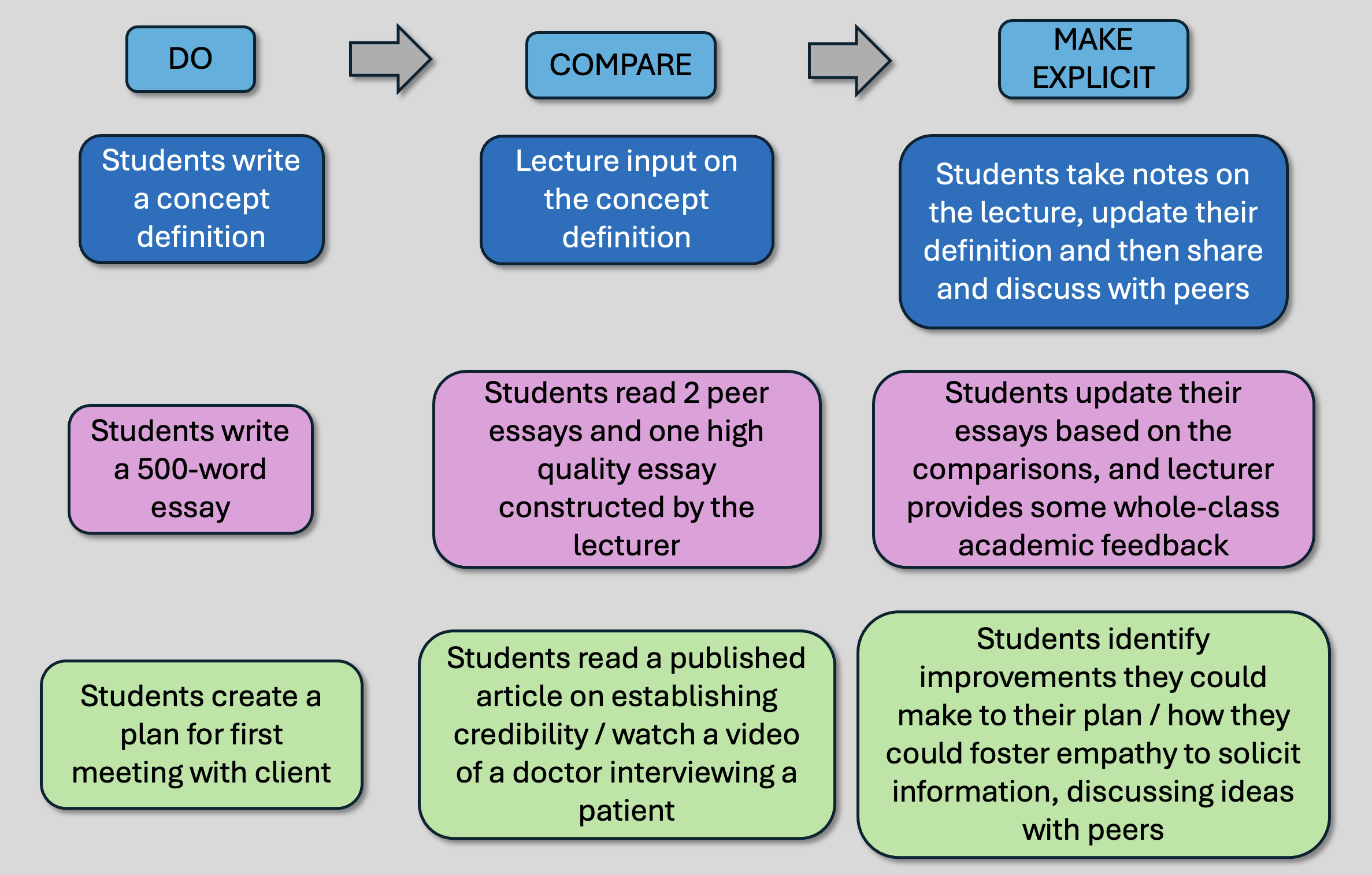

Nicol argues that academic feedback is wrongly conceived as the comments that lecturers leave on students’ work. Rather, students can be assisted to generate inner feedback from sources other than comments on their work – including from documents, readings, lectures, learning outcomes, rubrics, and the observation of others – by comparing themselves with these external references. Generating student inner academic feedback can in turn reduce lecturer workload from feedback commenting.

The process of generating inner feedback works when students first do some work, then compare with an external resource, and then make explicit outputs of those comparisons.

Below are some examples of how this might work in practice:

Reflective Coversheets

Staff may think about a Reflective Feedback Coversheet or a Student feedback request form. These enable students to demonstrate self assessment and application of feedback via assignment coversheet. They can help in generating dialogue in assessment feedback (see Bloxham, Sue, and Liz Campbell. 2010. Generating dialogue in assessment feedback: Exploring the use of interactive cover sheets. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 35 (3).) they also ensure emphasis has been paid to how students have engaged with prior feedback.

The UCL Arena Centre for Research-based Education has created the below example that is downloadable from the UCL Arena teaching toolkit Using forms (proformas) for feedback.

Example student feedback request form

Responsibility for the provision of useful feedback is shared between you and your assessors. Please help to make the feedback you receive as useful as possible by completing the following form and attaching it to your submission.

Name:

Module title:

Deadline:

I would particularly like feedback on the following (e.g. how I have laid out the problems etc.):

I am aware that I have made the following mistakes and would/would not like feedback on remedying them (please delete appropriate):

Note: Students should make every effort to seek help when they are aware of mistakes in their work prior to submission. However, we are aware that this is not always possible.

I have previously received the following feedback:

I have used it in this piece of work as follows:

Signed:

Date:

References

Bahula , T, & Kay, R. (2021). Exploring Student Perceptions of Video-Based Feedback in Higher Education: A Systematic Review of the Literature . Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, 21(4). https://doi.org/10.33423/jhetp.v21i4.4224

Boud, David & Elizabeth Molloy (2013) Rethinking models of feedback for learning: the challenge of design, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 38:6, 698-712, DOI: 10.1080/02602938.2012.691462

Carless, David, & David Boud (2018) The development of student feedback literacy: enabling uptake of feedback, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43:8, 1315-1325, DOI: 10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354

Nicol, David (2010) From monologue to dialogue: improving written feedback processes in mass higher education, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35:5, 501-517, DOI: 10.1080/02602931003786559

Nicol, David (2022): "Turning Active Learning into Active Feedback", Introductory Guide from Active Feedback Toolkit, Adam Smith Business School. https://doi.org/10.25416/NTR.19929290

Share your feedback

Where Next?

Take your pick of these related pages to this one:

Co-Creation in Assessment

Authentic Assessment

Assessment Compendium

Assessment and Feedback Literacy

Learning Design and Preparing to Teach

Learning Enhancement