Marking and Moderation

Getting Started

This section provides a range of resources and advice to assist and support academic staff and Schools to enhance their approaches to marking and moderation.

The resources linked below have been designed to support and facilitate the implementation of the University’s Marking and Moderation Policy. It is divided into the following pages:

The University Marking and Moderation Policy

Developing and Employing Assessment Criteria

Social Moderation and Calibration

Rubrics

To support all of these activities, further advice and guidance can be obtained from the Learning and Teaching Academy (email LTAcademy@Cardiff.ac.uk.)

The Deeper Dive section at the bottom of the page contains further reading and useful resources, including exemplar generic assessment criteria recently developed by Schools, and a Microsoft Form for use with social moderation exercises.

Deeper Dive

The University Marking and Moderation Policy

As approved by Senate, November 2023.

Developing and Employing Assessment Criteria

There are a number of different ways through which Schools / Programmes can develop frameworks to support consistent marking in ‘subjective’ assessments. This section has been put together to support Schools in meeting the minimum requirements set out in the University’s Marking and Moderation Policy, and to guide them when they need to go beyond these. It includes advice and guidance on a range of activities that Schools may choose to adopt that have been identified as examples of effective practice.

In addition to this guidance, an extensive range of help and bespoke support to implement the Marking and Moderation Policy is available from the Learning and Teaching Academy. Staff are therefore advised to contact and work with colleagues in the Academy to support the implementation of the Policy (email LTAcademy@Cardiff.ac.uk.)

What needs to be produced?

Schools/Programme Generic Criteria

All Schools will have and make available to students a set of generic assessment criteria, to provide an overarching indication of the academic standards that students will be expected to demonstrate in assessed work.

| Generic Criteria:

Generic criteria will typically focus on criteria such as the following:

However, Schools may choose criteria most appropriate to their programmes, depending, for example, on whether the emphasis is more academic or practical. Different criteria may be developed for different programmes as deemed necessary. |

|

For undergraduate awards, Schools should develop descriptors for their chosen criteria at levels 4, 5 and 6, covering:

|

For taught postgraduate awards, Schools should develop descriptors for their chosen criteria, covering:

|

| Descriptors at all levels should be aligned with the descriptors for awards in the Frameworks for Higher Education Qualifications of UK Degree-Awarding Bodies. | |

What we advise you to produce

Task Specific Criteria

| It is good practice for staff to develop and make available task specific assessment criteria to students, and to adopt a co-creation approach to this with students, to provide an indication of the academic standards that students will be expected to demonstrate in that assessment. Task specific criteria should align with the module learning outcomes being assessed in that task. | |

For undergraduate awards, staff should develop descriptors appropriate to the level of that module aligned with the learning outcomes being assessed in that task, which cover:

|

For taught postgraduate awards, staff should develop descriptors aligned with the learning outcomes being assessed in that task, which cover:

|

Further information and a number of case studies that discuss co-creation in assessment are available here.

How to Develop Good Assessment Criteria and Rubrics

Good, clear assessment criteria are appreciated by students and help to ensure that assessments are seen as fair, transparent, and consistent.

Well-designed assessment criteria:

Question(s) to ask:

- How well do the criteria align with programme / module learning outcomes?

What this means:

The School / Programme generic criteria should align with the programme learning outcomes, while task specific criteria should align with the module learning outcomes being assessed in that task. Being consistent in aligning the learning outcomes with the assessment criteria helps promote clarity.

Question(s) to ask:

- Are the criteria observable and measurable?

- If the criteria are used for similar tasks across the programme, is there consistency in the use of language, promoting students’ ability to self-assess their progress?

- Will the be criteria unpacked in assignment briefs?

What this means:

Criteria should be clear and understandable to students and other stakeholders. Consideration should be given to the level of detail: students need to be able to understand what is expected of them, whilst also being able to manage cognitive load. The number of criteria attached to a specific task should be limited, to ensure that these are both clear to students and manageable by markers.

Question(s) to ask:

- Is the number of criteria manageable (between 3 and 6 criteria strikes a balance by avoiding overwhelming complexity and ensuring meaningful distinctions between criteria)?

- Are the criteria sufficiently differentiated or do they overlap?

- How relevant are the criteria for the nature of the task/type and variety of assessments across the programme?

What this means:

Criteria need to be sufficiently distinct from each other, to ensure that they allow a more holistic approach to marking. Criteria need to be seen by students as an indication of achievement rather than an exact measurement.

Question(s) to ask:

- Do the criteria avoid subjective descriptors (e.g. ‘Excellent’, ‘very good’, ‘fair’)?

- Do the criteria avoid references to quality (e.g. logically, effectively)?

What this means:

Assessment criteria should avoid, where possible, entirely subjective descriptors, these being open to different interpretation encouraging staff to retrospectively fit prospective marks to criteria.

What this means:

Assessment criteria should encourage students to show creativity, spontaneity, and originality. Particularly important at levels 6 and 7, assessment criteria that avoid these can potentially restrict or restrain learners.

Question(s) to ask:

- Are the criteria appropriate for the level of study?

What this means:

Assessment criteria should be created by developing the descriptor for the basic ‘pass’ first. Use this to indicate what is required at a pass level, but in a positive way. Try to avoid terms such as ‘inadequate’, ‘limited’, ‘inaccurate’, which are more typically used to describe work that has not met the learning outcomes.

From a practical perspective, staff may find it useful to initially plan criteria by creating a grid with colleague(s). Engaging in discussion can help the articulation of difficult ideas. Having drafted your set of criteria, it is then useful to ask yourself the critical question: do the criteria enable students to identify how well they have done? If they may struggle to do this, the criteria may need some further work.

Creating assessment criteria in collaboration with students

How this might work:

- Students read sample assessments and use them to decide on marking criteria.

- A committee of students develops marking criteria, which would then be compared with the staff version, and a final version would be discussed.

- The students' marking criteria are used for peer assessment and self-assessment.

Read here about a project at the University of Cumbria where staff and students co-created assessment criteria, concluding that the staff version was too complex, using academic discourse, and the students' version was too simple, and that the criteria needed to be made accessible to students - considering the question, 'For whom are these [criteria] created?'

Using criteria for marking and moderation

Having good clear criteria is an important element of the support that goes into marking. However, it is equally important to consider how these will be used; this being key to fair and consistent marking and moderation. This can be achieved by:

- Ensuring that all markers have a shared understanding of academic standards, by undertaking social moderation exercises and/or by testing the criteria against an initial sample;

- Ensuring that students know where the criteria can be accessed and reminding them of the role that academic judgement will play in marking.

- Reviewing the marks you are proposing to award to the first few papers marked to ensure your judgements are aligned with the criteria;

- When half-way through marking, by returning to a small sample and reviewing these, to ensure marking remains aligned with the criteria and that judgements have not changed through the marking process ;

- (When marking as a team) reviewing the outcomes reached on any ‘control’ papers, to either enable comparison of different markers and/or to ‘recalibrate’ understanding;

- Developing feedback comments that relate to specific criteria, to help enable students to better use feedback to improve in specific areas. (Do remember, however, that feedback is not and should not be provided solely as comments that seek to explain and/or justify the mark.)

- Completing the relevant sections in the moderation proforma and by then providing this, together with access to the scripts being moderated, to the moderator(s);

- Having the moderator(s) then complete the form and then arranging to meet and discuss the outcomes from this with the first marker (many research studies having shown that meeting and openly and honestly discussing standards is key to developing the shared understanding of standards);

- Ensuring the completed form is made available to external examiners;

- By Examining Boards annually reviewing, and, where relevant, revising and updating their criteria to ensure that they both accurately communicate expectations and remain aligned with sector expectations;

[N.B. Much of the research into moderation has highlighted the need for meetings and discussion between markers to be undertaken in an open, respectful, and transparent way. Research has further shown that ‘double blind marking’ can lead to defensiveness on the part of second markers; markers avoiding either very high or low marks that could suggest marking out of line with criteria. However, very low or high marks are also often avoided by second markers who already know the first mark; their judgement having been influenced by the original judgement.]

Social Moderation and Calibration

“Assessment is largely dependent upon professional judgement, and confidence in such judgement requires the establishment of appropriate forums for the development and sharing of standards within and between disciplinary and professional communities.”

Tenet 6: Price et al (2008)

The University’s Marking and Moderation Policy aims to ensure that all markers have confidence when assessing student work and are fair and consistent in their judgements. It seeks to achieve this by placing greater emphasis on the exercises undertaken in advance of marking, such as calibration and social moderation.

This section provides information on a number of different ways in which calibration and social moderation activities can be held, depending on numbers, assessment methods, and discipline. Specifically, the first part of this guidance provides further information on how annual calibration events operate; these meetings are seen as a crucial precursor to the activities that the Marking and Moderation Policy requires to be undertaken on individual modules. To support all of these activities, further advice and guidance can be obtained from the Learning and Teaching Academy (email LTAcademy@Cardiff.ac.uk.)

Annual ‘Structured Calibration’ Exercises

Whilst these exercises can be conducted in a number of different ways, typically, these workshops involve all markers first (re)marking a small number of existing submissions, then working together to discuss, negotiate, and (hopefully) agree a mark for each of the assessments. The below list provides further details of each of the stages typically undertaken in a structured calibration meeting.

Identifying the focus and materials that will be used in the workshop

Whilst calibration meetings are normally held in person (and benefit from the social interaction they help generate), most of the preparation and initial stages can be undertaken online. First, you need to identify both the module and the scripts that you wish to use in the workshop. For example, you may want to focus on final year projects or dissertations, equally, you could choose a level 4 module from year 1; depending on where consistent marking have been identified as a possible issue. Whichever module is chosen, you’ll need to agree this with the module leader and identify the specific scripts that you will be asking colleagues to re-mark. Students’ identities must also be removed from the scripts, before these are then circulated, together with the module learning outcomes, assessment brief, relevant assessment criteria and other key reference documents to colleagues due to attend the workshop.

HINTS and TIPS – The choice of module and scripts is important; in that you’ll need to ensure that staff are sufficiently familiar with the subject material to be able to mark the exemplars and have the time to complete this marking. Hence, it may be tempting to choose a short piece of work from a year-one module. However, there may be less value in choosing first year work, given it does not contribute to degree classifications and may be less varied in nature. You may also want to choose scripts that were originally marked as close to the pass mark and/or other boundaries. Doing so will give you an opportunity to better identify and share the characteristics that help define scripts at these points. Include a clear deadline by which all staff will enter their marks for these assessments.

Distributing the materials and record the outcomes from the pre-work

Having identified the scripts that will be used in the workshop, copies of these need to be distributed to all scheduled attendees, with a request that they mark the work in advance of the event and enter their mark with brief summary comments via an online system. An example, using Microsoft Forms (which has also been designed so that the results from this exercise can be summarised and displayed on a screen) can be found in the deeper dive.

HINTS and TIPS – To ensure staff have the time they need to complete the marking in advance of the event, make sure that the scripts are distributed well in advance of the face-to-face workshop. You should also request staff not to discuss their mark or comments with colleagues in advance of the event, given the different ways in which this could impact negatively on the workshop.

Starting the workshop, setting the scene, and agreeing the ways of working

At the start of the face-to-face element of the workshop, facilitators typically first present the outcomes from the marking exercise. Given the degree of variability that this exercise normally shows, you may want to also use this as an opportunity to present the summary findings from research, findings that show variation is typical and an inevitable consequence of the ‘tacit’ way in which individual conceptions of academic standards are developed.

HINTS and TIPS – Setting the right tone and finding ways in which calibration exercises can be both productive and effective are key to their success. In particular, you will need to find ways through which all colleagues can equally contribute and input to this. You may find some colleagues are reluctant to recognise or accept the research findings that show significant variation in marking, and/or some who believe they are entirely consistent in their own marking and have a better understanding of academic standards than others.

All participants working in small groups

The first stage in a calibration meeting involves participants working in a number of small groups to discuss and review their initial judgements, and to [try and find] a common understanding. All groups should be asked to identify the different ‘aspects of quality’ that have helped inform their judgements, and to record and share this information. This information should help each group to find staff who may accept the need for their original mark to be raised or lowered, and thus come to a consensus as a small group. Staff should be encouraged to utilise the module learning outcomes and assessment criteria, to ensure that the original judgements align accurately with these and that no additional factors have been brought in to inform these judgements. At the conclusion of this exercise, ask one member from each group to briefly feedback each group’s findings and identify how the group’s mark may have changed, facilitators noting and capturing these key outcomes on a flipchart or screen.

HINTS and TIPS – It is important to take care to set up groups that will work effectively and in which all individual group members can contribute. While you should not expect all groups to agree a single mark at this point, the range of marks allocated to individual scripts will likely have narrowed, something that you should record on the screen and/or flipchart being used for this purpose.

From small groups to larger groups

Having recorded the different outcomes and provisional marks allocated by each of the small groups, the next stage is to open up discussion between and across the different groups. Again, the purpose of this exercise is to try to persuade and convince each group to consider either raising or lowing their mark, this discussion needs to draw on the learning and assessment criteria for that assignment. For example, do all of the groups share the same understanding as to what constitutes ‘good’ work, or have one group placed more emphasis on one individual criterion that the others feel is less important. Use the outcomes from the cross-table discussions to identify whether individual groups are happy to further shift their mark. While you may still not be able to achieve a whole-room consensus on a mark, it is likely that you will have helped individual members of staff further develop (and better align) their own personal sense of academic standards, which in itself can significantly reduce variability in marking.

HINTS and TIPS – Active listening and ensuring that there are opportunities for all to contribute and feedback to this discussion are essential. Maintaining a positive and respectful approach to the group discussion can also make colleagues more willing to adjust their mark and can prevent discussions from being dominated by anyone who is dogmatic and/or convinced of the accuracy of their own marking.

Reflections and conclusions

At the end of the shared discussion, it is important to provide some space and time to allow individuals to reflect on the exercise they have just participated in and to identify any changes they have identified to their own individual marking practice. Where possible, ask participants to share their lessons learned.

HINTS and TIPS – While it can be tempting at this point to draw the session to a close, there is much value that can be gained from staff sharing their reflections on this exercise. It is a good idea to use ‘active questions’ to prompt colleagues to share their reflections and deter overly critical and/or negative comments.

Sharing and communicating the outcomes

After the workshop it is good practice to feedback a summary of this exercise to your students. Whilst this does not need to include details of the modules, marks, or individual assessments that you looked at, feeding back will help demonstrate to students the importance that you give to academic standards, and can provide useful information to students on the ways in which specific criteria are being used.

HINTS and TIPS – Care needs to be taken when feeding back the outcomes from calibration activities with students; to ensure students can both acquire a better understanding as to how markers will utilise and interpret the assessment criteria when marking, and, at the same time, better understand the natural variability that accompanies ‘academic judgement’.

Managing Social Moderation Within Individual Modules

There are a range of different tools and techniques that can be used to support pre-marking moderation in individual modules. Hence, the below is not an exhaustive list; the key being, that whatever method is adopted, that all markers develop a shared view on expected standards, a common understanding of the meaning and weighting that will be given to different criteria, and thus, allowing markers to grade individual assessments more consistently and with confidence. Below is a brief list of some of the ways in which social moderation can be conducted for individual assessments.

Pre-teaching marking exercise to mark and discuss exemplar assignments (e.g., from the previous year)

Utilising a similar methodology to that typically used in School calibration events (albeit with less of a need to record the judgements markers first reach, or to start working in small groups etc.), it is good practice for markers and/or markers and moderators to meet before marking starts. In these meetings, all parties should first mark a number of existing scripts. They then need to compare marks and discuss and negotiate a shared mark, utilising the assessment criteria and learning outcomes for that module. The sample assessments should be used to open up discussion about academic standards and allow the module team to develop a common view of the key aspects of quality expected, before the start of the module. This will increase the likelihood of students receiving consistent advice.

Team marking sessions/‘Marking Parties’

In modules with a number of markers, and often used as an extension of initial marking exercises, it can be helpful for a marking team to come together to mark assessments. Such exercises work well when they allow discussion and comparison of judgements as they are made, to quickly build a shared understanding of academic standards across markers. Some colleagues have even reported that such events make marking a more enjoyable and collegial exercise, although it can be difficult to find time to mark simultaneously. It thus requires a commitment to participate from all markers to work well.

Pre-teaching briefing to markers on the expectations for the assessment

Prior to starting marking, particularly if it is new module and/or should no exemplars be available to pre-mark, it can be useful for the marking team to get together and discuss the assessment brief and assessment criteria. Whilst this will increase the chance that all markers will develop a similar grasp of the assessment requirements and provide students in different groups with consistent advice about the assessment, the value of using exemplars to support this should not be underestimated.

Peer scrutiny and discussion of a module’s assessment, instructions, criteria etc.

Often undertaken by a moderator in advance of assessment submission, the relative effectiveness of this will be dependent on the type of scrutiny. It can be positive if it engenders conversations about the expected quality of work, but a simple 'tick box' pro forma may encourage superficial scrutiny. Care also needs to be taken so that the moderator also recognises their own assumptions about the meaning of assessment brief, the assessment criteria, and/or the expected quality of work.

Whole course team development and enactment of programme assessment strategy

This can ensure that module leaders see how the assessment in their module contributes to meeting programme learning outcomes, particularly where discussion involves expectations about academic standards at each level of the course, progression, and the balance between assessment of and for learning.

Limited double marking

Although there is little evidence to suggest that (blind) double marking and second marking lead to a better sense of shared standards, here are some scenarios where some limited double marking may be beneficial:

Borderline marks: Double marking can help clarify borderline cases where there is uncertainty. This can help ensure that students are not unfairly either penalised or rewarded.

High-stakes assessments: For high-stakes assessments, such as dissertations, double marking may provide a higher level of confidence. Here markers should still ensure that there is a shared understanding of standards and criteria prior to marking.

Smaller cohorts: Where the sample/cohort size is smaller, double marking may be more feasible.

Subjective assessments: certain disciplines, and certain types of assessment, involve a high element of subjectivity. An example of this would be musical recitals, where subjective judgement is inevitable. In such cases, double marking has clear benefits.

Performative assessments: for reasons other than subjectivity, assessments involving live performance may benefit from double marking where possible. There can be considerable savings to time if oral examinations and presentations, for example, are live double marked, rather than second marked/moderated from recordings.

Where students have submitted work in different formats: Where this has been permitted in line with the new policy on reasonable adjustments, it is possible that marking may move away from the agreed criteria. Pre-marking social moderation discussions should address this possibility, but there may be a case for including different submission formats in a double marked sample to ensure consistency and the appropriate application of assessment criteria.

Moderation of extended projects first marked by supervisors

There may be some conflict between the potential for supervisor bias and the need for subject expertise in marking and moderating extended projects. There is some evidence to show that supervisors may mark only marginally higher than independent academics (McQuade et al., 2020), and there is therefore flexibility within the Marking and Moderation Policy around the expectation for anonymous marking. In selecting moderators for extended projects, factors such as project marking experience will be important. The most important consideration, however, is subject expertise. It is important to bear in mind that markers and moderators without an appropriate level of subject knowledge may award significantly lower marks (McQuade et al., 2020).

Rubrics

It is important to consider the pedagogical value of any tool we use in assessment. What value will it add to the student experience and student outcomes? There can be considerable variability in the usefulness of rubrics depending on how they are introduced and implemented. They must be used as more than a tick-list for marking if they are going to have a positive impact on student confidence and outcomes.

One aim with the introduction of School/Programme level generic assessment criteria in the new Marking and Moderation Policy is to enhance the student experience by providing consistency of approach. Generic assessment criteria can be used as an overarching frame of reference to inform task-specific rubrics. A study by Taylor et al. (2024) showed that students prized consistency in layout and in the language used across modules at the same level. Students should be given confidence that rubrics are not just designed with an individual lecturer’s preferences in mind.

Ways to ensure the usefulness of rubrics:

Ultimately, rubrics will look very different depending on the discipline: a lab report rubric may be a very prescriptive ‘laundry list’, whereas a rubric for Creative Writing will leave room for student creativity and subjective academic judgements.

Use rubrics for peer and self-assessment in a formative context

It is important to consider how rubrics are introduced to students. Rather than simply posting rubrics to Learning Central, consider devoting time to introducing and discussing the rubric for an assessment in a learning session. This could include

- explanations

- opportunities for questions

- peer discussion to deduce meaning

- opportunities to apply the rubric to a sample assessment

- directing students to targeted grade boundaries

It is certainly worth dedicating time to introducing rubrics to students where this is likely to increase student confidence and impact performance (Bolton 2006).

You might suggest that students engage with rubrics in a number of ways to enhance their outcomes:

- planning support in the early stages of an assignment

- a summative checklist in review of a completed assignment

- a guide referred to throughout the writing process

- a target setting tool

(from Taylor et al. 2024)

Use clear and detailed language

A common concern for students is the lack of clarity and transparency in the language used in rubrics, with students wanting specific details within grade boundaries (Taylor et al. 2024). Try to avoid ambiguity in the language guiding progressions across grade boundaries. It may not be helpful to students to use large amounts of repetition, changing only one or two words in the descriptors. Consider instead:

- including numerical components e.g. the number of points expected at different grade boundaries

- clear identification of key words e.g. by using bold or italics

- specific items noted for different grade boundaries

See this example for how a rubric might look, taking the above three points into consideration.

Ensure scope for creativity

Include wording that respects student autonomy, creativity and originality, particularly where these elements are relevant to the assessment. You might include phrases like ‘demonstrates innovative thinking’, ‘applies concepts in unique ways’, or ‘engages with complex and challenging ideas’.

Please see the guidance on Using Rubrics in Turnitin Feedback Studio and how to Create Rubrics in Blackboard.

If you only do one thing…. try to include some in-session rubric analysis to:

- provide direct instruction in how to use rubrics, especially as a tool for gaining higher grades

- exemplify how different grade boundaries might be applied to different written outcomes

Deeper Dive

References

Baume, D., et.al., 2004. What is happening when we assess, and how can we use our understanding of this to improve assessment? Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 29 (4), pp.451–477.

Bloxham S. (2009). Marking and moderation in the UK: false assumptions and wasted resources.

Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 34(2), tud. 209-220.

Bloxham, S., Boyd, P. and Orr, S., 2011. Mark my words: the role of assessment criteria in UK higher education grading practices. Studies in Higher Education, 36 (6), pp.655–670.

Bolton, F.C. 2006. Rubrics and Adult Learners: Andragogy and Assessment. Progress Assessment Update 18(3), pp. 5-6.

Grainger, P., Purnell, K. and Zipf, R., 2008. Judging quality through substantive conversations between markers. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 33 (2), pp.133–42.

Higher Education Academy, 2012. A Marked Improvement: Transforming assessment in higher education. Available at: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/system/files/a_marked_improvement.pdf [Accessed October 2024].

Hunter, K. & Docherty, P., 2011. Reducing variation in the assessment of student writing, Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 36 (1), pp. 109–24.

McQuade, R., Kometa, S., Brown, J., Bevitt, D. and Hall, J., 2020. Research project assessments and supervisor marking: maintaining academic rigour through robust reconciliation processes. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(8), pp.1181-1191.

DOI: 10.1080/02602938.2020.1726284

Moss, P.A. and Schutz, A. 2001. Educational standards, assessment and the search for consensus. American Educational Research Journal, 38 (1), pp.37–70.

Newstead, S.E. 2002. Examining the examiners; why are we so bad at assessing students? Psychology Learning and Teaching, 2, 70-75.

Norton, L. 2004, Using assessment criteria as learning criteria: a case study in psychology, Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 29 (6) pp. 687-702.

O’Donovan, B., Price, M. and Rust, C., 2004. Know what I mean? Enhancing student understanding of assessment standards and criteria. Teaching in Higher Education, 9 (3), pp.145–158.

Pandero, E. and Romero, M. 2014. To Rubric or Not to Rubric? The Effects of Self-Assessment on Self-Regulation, Performance and Self-Efficacy. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice 21(2), pp. 133-148. doi:10.1080/0969594X.2013.877872.

Price, M., 2005. Assessment Standards: The Role of Communities of Practice and the Scholarship of Assessment. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 30(3), pp.215–230.

Price, M., 2008. The Weston Manor Group. Assessment Standards: a manifesto for change.

Sadler, D. R., 2012. Assuring academic achievement standards: from moderation to calibration. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice, 20(1), pp.5–19.

Saunders, M. a Davis, S. (1998). The use of assessment criteria to ensure consistency of marking: some implications for good practice, Quality Assurance in Education, 6(3), tud. 162-171.

Taylor, B., Kisby, S. and Reedy, A. 2024. Rubrics in higher education: an exploration of undergraduate students’ understanding and perspectives. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 49(6), pp. 799-809. doi:10.1080/02602938.2023.2299330

Watty, K., et al., 2013. Social moderation, assessment and assuring standards for accounting graduates. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 39 (4), pp.461–478.

Glossary of terms

For definitions of ket terms used in the Marking and Moderation Policy, see this Glossary of Terms.

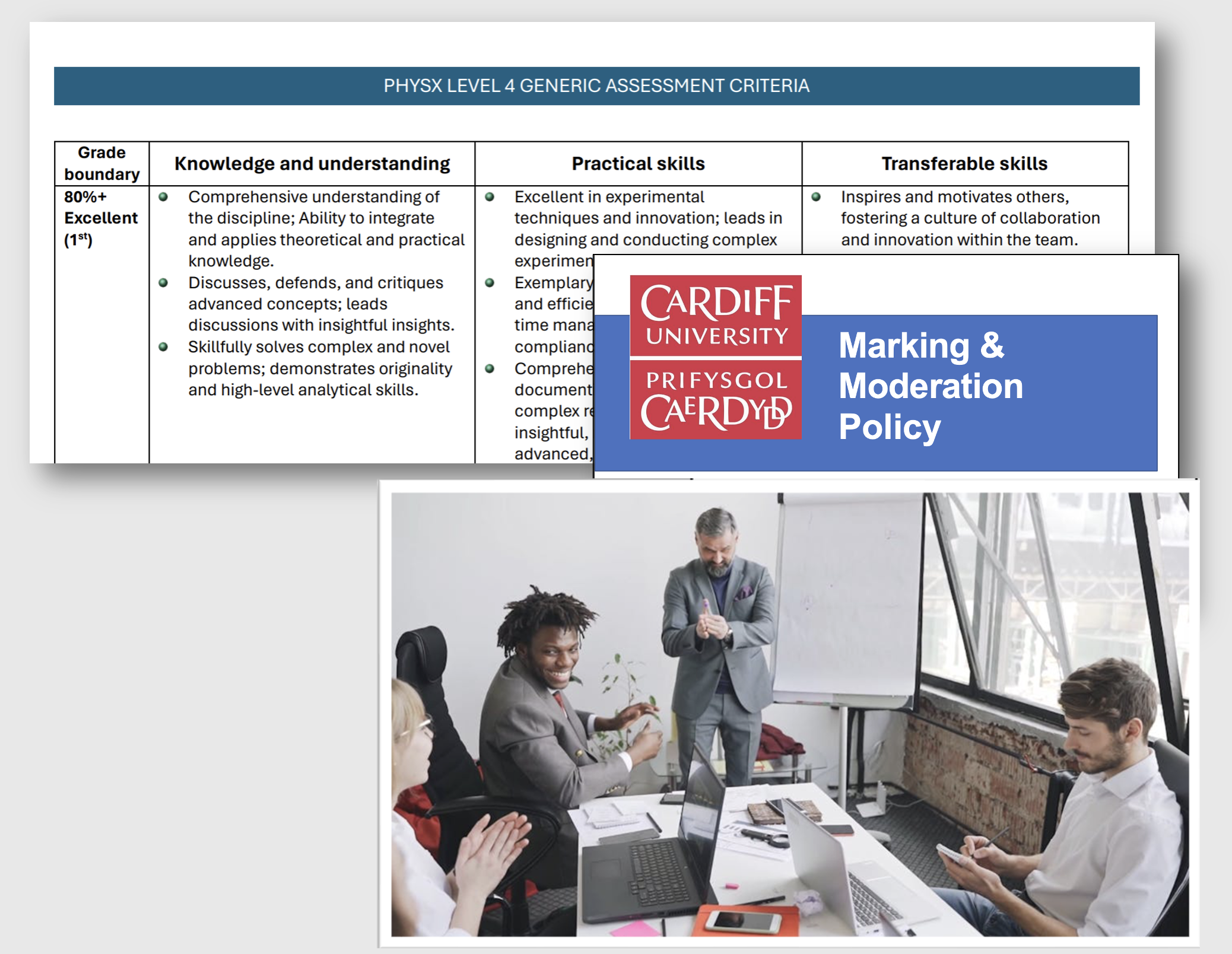

Exemplar assessment criteria

These Exemplar Assessment Criteria, levels 4,5 and 6 were co-developed with input from a group of recently graduated students. Discussion with the students in advance of this task showed that, like many, they were often unclear as to what was expected of them in individual assignments, the meaning of many of the criterion in the documents they were given being unclear to them. The students also noted that examples of previous students’ work help bring to life the subjective qualifiers attached to many sets of criteria. It was an exercise that showed the value of Schools working with their students when developing criteria.

The exemplars, which benefited from the use the students made of artificial intelligence systems, are provided as a starting point for Schools. Hence, it is suggested that Schools may wish to use these and re-work them, so that they better focus on the qualities you expect to find in student work within their discipline. It is recommended that this exercise be undertaken in partnership with your students. Schools seeking support to develop assessment criteria should contact the Learning and Teaching Academy via ltacademy@cardiff.ac.uk.

Developing generic assessment criteria in readiness for the implementation of the Marking and Moderation policy.

In line with the new policy on marking and moderation, the School of Architecture has developed a set of generic assessment criteria grouped under the three main categories of Knowing, Acting and Being, as per (Barnett and Coate, 2005). There are 7 levels listed for each category and explanatory text is provided for each level in each category to help students understand the relationship between the level of achievement to the marks allocated. It is expected that, depending on the type of assessment (e.g. report, portfolio, reflective essay, project etc), the weightings applicable to each category will vary. The guidance also outlines a process through which task-specific criteria and rubrics will be developed and grouped under these three categories, based on (Roberts, 2023). These will be phrased simply, to explain the type of evidence that examiners will be looking for in the work submitted.

This new guidance does not aim to provide a blanket approach to assessment and creation of rubrics but is rather aimed at providing a standardised basis or a reference point for aligning existing practices. It is expected that this streamlined approach will enable achieving a level of consistency in practices across all programmes, facilitating both sharing of modules without confusing students, and improving overall staff experience with marking and social moderation. The guidance also advises on checks and alignment required in the event of maintaining existing assessment criteria and requires that staff more broadly engage in discussions with cohorts to enable co-creation.

Eleni Ampatzi. DPGT and co-DLT, School of Architecture.

R. Barnett, K. Coate. Engaging the Curriculum in Higher Education. Open University Press, Berkshire (2005)

A. Roberts. Productive-Disruptive: spaces of exploration in-between architectural pedagogy and practice, AAE Conference, Cardiff 12-15th July 2023

PHYSX Level 4 Generic Assessment Criteria

PHYSX Level 5 Generic Assessment Criteria

Using generative-AI to develop generic assessment criteria

Dr James Redman, Assessment and Feedback Lead for Chemistry, describes the process of using generative-AI in creating School-wide Generic Assessment Criteria:

“My original versions had 5 categories and were quite verbose so became unwieldy in tabular form. I merged some of the categories, as there was significant overlap, and slimmed down the text.

For levels 6 and 7, GPT4 did a reasonable job at providing a starting point. I had to extensively edit and tone down levels 4 and 5 as there was too much emphasis on ground-breaking research which was not appropriate.

My prompt contained essentially the entire text that describes 1st and pass at levels 6 and 7 from the QAA Subject Benchmark Statement for Chemistry, the text from the relevant column from the generic criteria, some context about the persona that the model should adopt (an academic in UK higher education), and instructions on the task to be performed.”

Clinical Practice: Unseen case report marking criteria

Social moderation Pre-event form

Share Your Feedback

Where Next?

Take your pick of these related pages to this one: