Teamwork

Getting Started

This toolkit has been collaboratively developed by an interdisciplinary team of CU educators, experienced at supporting productive teamwork within their practice over a sustained period with positive student outcomes. Recognising that teamwork can be used in multiple educational contexts, in different ways and for different reasons, our goal is transferability rather than replicability of best-practice methods. The following content is intended to be a series of prompts, whether you are new to teamwork pedagogies or reflecting on and refining existing practice. We welcome further innovations and insights from the wider CU community.

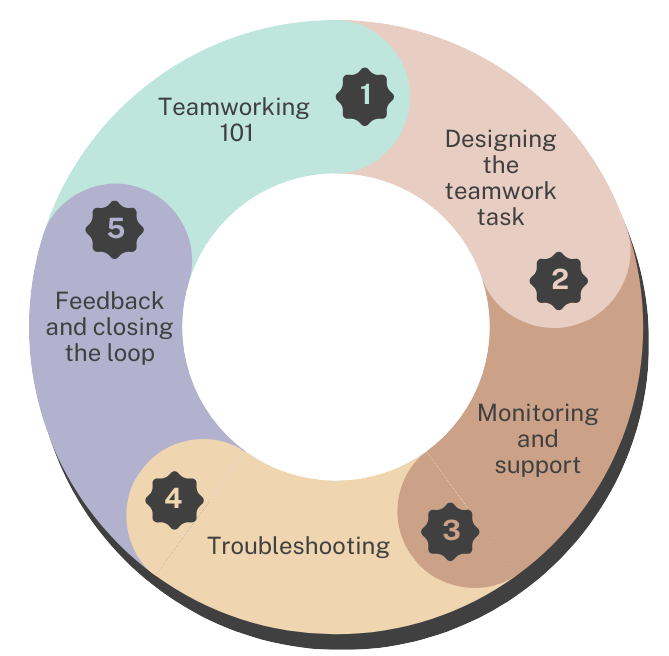

1. Teamworking 101

2. Designing the teamwork task

3. Monitoring and support

4. Troubleshooting

5. Feedback and closing the loop

Teamworking 101

Key points

- Transferable skills development: assess whether teamwork will effectively foster key skills such as collaboration, communication, critical thinking, conflict resolution, and reflective awareness, which are valuable in higher education and beyond.

- Enhancing student experience: determine if teamwork will enrich the learning environment by promoting peer-to-peer engagement, deeper learning, and personal development, fostering a sense of belonging and mutual support within the learning community.

- Workload management: consider both staff and student perspectives regarding workload. Evaluate if teamwork can lead to a balanced distribution of workload among students and whether it requires significant planning and management effort from staff.

- Team dynamics and structure: ensure clear communication of team roles, responsibilities, and expectations. Plan for regular team communication to maintain momentum and address challenges like freeloading or over-contributing.

- Assessment considerations: reflect on how teamwork aligns with the pedagogical rationale and learning outcomes. Consider the incorporation of peer assessment and alternative assessment formats to ensure fairness and transparency.

- Contextual suitability: evaluate the suitability of teamwork in the specific educational context, including the cohort’s readiness and experience in working collaboratively, and the alignment with the course’s learning objectives.

Teamwork vs group work

Teamwork can be defined as a process involving two or more students working toward common goals, interdependently, with individual accountability (Riebe et al 2016). In group work, members tend to focus on individual strengths and goals to get work done. In essence, teamwork encourages students to work cooperatively on the task rather than collaboratively.

Teamwork can be used in a variety of ways and situations, motivated by a range of internal and external drivers. Pedagogies that incorporate teamwork include:

- Experiential team-based learning (TBL), in which students learn through peer-to-peer interactions and by doing. This emphasises learning through action and reflection.

- Collaborative learning, which prioritises mutual engagement in a coordinated effort to solve problems together.

- Problem-based learning (PBL), in which students learn by doing, often working on working-world problems.

- Project-based learning, where teams work on projects over extended periods, integrating various skills and disciplines.

- Simulating authentic collaborative practices, e.g. PBL or scenario-based learning mirroring industry or professional roles and practices.

- Explicit teaching of collaborative/cooperative team skills, such as ‘Experiential Entrepreneurship Education’.

Understanding the differences between group work and teamwork is essential in educational settings for both staff and students; the former involves individuals completing separate tasks, while the latter requires cohesive, interdependent efforts. A clear distinction is essential to prevent students from defaulting to isolated roles that reflect group work rather than true teamwork. Educators must emphasise collective responsibility in assessments to ensure students engage with and value the team's integrated success over individual achievements.

The next section explores the rationale behind employing teamwork in academic contexts, highlighting its distinct advantages over more segmented group work approaches.

Why use teamwork?

Develop Transferable Skills

“(teamwork) has helped me broaden my perspective and taught me to learn to work together, get more done in a group, and learn from those around me. But even beyond practice, when one leaves university and steps into the real world, working with others is perhaps the most important skill you can have. The world is full of 'other individuals' who you will need to be able to build relationships with, learn from, and handle your responses to.” (CU student, 2021)

Teamwork is not just a pedagogical choice; it is a vital tool for developing key transferable skills that are highly valued in higher education and beyond.

- Ability to work collaboratively and cooperatively in teams – face-to-face and remotely

- Ability to listen to others and provide constructive feedback

- Creative thinking to build on existing ideas

- Conflict resolution to mediate disagreements

- Time and process management skills

- Reflective awareness

Through engaging in teamwork tasks, students can enhance their transferable skills including critical thinking, communication, leadership and problem-solving, whilst encouraging a sense of responsibility and accountability.

The teamwork task environment:

promotes peer-to-peer engagement and peer learning, long having been recognised as a much more powerful tool for learning than academic instruction (Mazur 1996; Vygotsky 1978) leading to a deeper level of learning and personal development that is based on peer-to-peer encounters and experiences.

strengthens the learning community, engendering a sense of belonging and maintaining ongoing mutual support within small group learning and teaching and can structure and support social integration within new cohorts.

can enhance outcomes such as the production of quality coursework artefacts. “...being able to bounce ideas off one another, allowing ideas to be continually pushed and adapted to produce the best outcome. Sharing ideas allowed the project to venture into a place that it might not have working on your own.” (CU student, 2021)

“(...teamwork) was beneficial to get to know our peers, to combine our skills advantageously towards a more efficient outcome. We had similar approaches, but I learned new ways to solve problems.” (CU student, 2022)

Reduce Workload

Staff perspective:

Team working can in itself be an approach to managing large cohorts that can lead to a reduction in overall assessment load. Whilst teamwork can be used productively as a tool to scaffold (independent) peer-led learning, thereby reducing teaching contact hours, there can be a significant additional workload in the planning and management of effective teamwork tasks. Teamworking empowers students to be accountable and collectively find ways to manage tasks, and this can be unpredictable and difficult to control and can result in additional workload for staff/educators in mediating between or chasing individuals. This toolkit suggests ways to structure smooth(er)-running teamwork scenarios from the outset.

Student perspective:

Giving students the skills and knowledge to foster a collaborative team-working environment at the very beginning, with proper task allocation, and shared responsibilities, will enhance motivation and accountability. This might involve showing students how to work as a team, how to structure and manage teams, and what to do when things go wrong.

Student teams can take ownership by thinking through the management of the task; breaking down the activity, setting interim deadlines, identifying individual skills, establishing needs, availability and balancing the workload, and creating a space that is supportive with open communication.

Considering, early on, how you will stay in regular communication within the team(s) is crucial to maintain momentum and address any potential challenges early on. Freeloading or over-contributing can disrupt team dynamics. It can be helpful to involve students in discussions on how to manage such situations at the very beginning. Doing so at a later stage will be more difficult.

One approach that can help mitigate such issues is the use of peer assessment for teamwork tasks. Whatever the outcome of the task, peer assessment gives all students within a team a voice, and can have an impact on final assessment. Another option that can run concurrently, is to offer an alternative assessment from the start. This can be used for prompt resolution of any team issues and/or can often be seen as a less attractive option.

It is not possible to foresee all outcomes. Ensure team tasks are clearly communicated and that teams know what is expected of them - as a team and as individuals. Prepare for the breakdown of team tasks early on, maintain open communications with teams, but be clear on their roles and responsibilities.

Challenging perceptions

“Students often perceive teamwork as unfair or harder than individual assignments, which can certainly be true. It is almost certainly easier to work individually to produce a piece of work, but students miss out on the critical transferrable skills that employers expect of the modern graduate.” (Francis, 2022).

On the other hand, the quality of work produced by a team can often (far) exceed that of the individuals. Marks for team-based assignments and the learning outcomes are often higher than for similar tasks carried out as an individual (Yorke and Knight, 2006).

If you are interested in exploring this further:

https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/news-and-views/i-love-group-worksaid-no-student-ever.

When and why use Teamwork?

Setting up team tasks

Implementing team-based assessments requires consideration and planning in order to enhance students' subject knowledge, develop vital transferable skills, and align with broader educational objectives. The success of these tasks hinges on how well they are set up, demanding attention to various aspects such as task design, team group dynamics, and assessment criteria. In this section, we will explore the key considerations that academics should keep in mind to ensure that team-based tasks are effective, equitable, and conducive to learning.

For teamwork to be effective consider:

Motives and rationale for conducting teamwork

- I have a large cohort and cannot mark that many assessments

- I have never used teamwork in my module before and I want to explore this to enhance the student experience in my teaching and learning

- I want to include more of the graduate attributes in my teaching and I think teamwork will help me to do this

- I want to embed more practical work/authentic assessment and students will need to work in teams to complete the exercise

- I want to strengthen the learning community and social integration within a new or existing cohort and teamwork would provide a structure to achieve this.

Are all educational contexts suitable for teamwork?

- What is the pedagogical rationale - e.g. enhancement to learning, student experience and development?

- How/ does this relate to existing (P)LOs?

- How experienced, knowledgeable, and equipped are the cohort to work together?

- Have you used teamwork before? If not, you are in the right place!

- (related) how much scaffolding is needed to support effective teamwork?

- Why teamwork?

- What is the aim of the team working task?

- What needs to be in place for teamwork to succeed?

- Do students know HOW to work in teams?

- What is the level of the student cohort?

- Will students work as teams in/outside of class, or both?

- Does it matter if teams are in different seminars?

- What do you hope to achieve through teamwork (that is distinct from other modes of learning?

Designing the teamwork task

Key points

- Team formation strategies: assess different methods for team formation, such as instructor-assigned teams or student self-selection, considering factors like balance, diversity, and specific roles within the team.

- Task design and focus: define the focus of the team task, including project duration, expected deliverables, necessary resources, and whether the task is credit-bearing or extra-curricular. Ensure that the task aligns with learning objectives and provides a clear and feasible challenge for students.

- Group size management: decide on the optimal group size based on the cohort size and manageability, considering factors like how the cohort divides into teams and the number of teams you can effectively supervise.

- Assessment framework: establish a clear and fair assessment strategy, determining whether to assess the final product, the teamwork process, or a combination of both. Consider including peer assessment, individual contributions, and how marks will be allocated.

- Monitoring and supporting team dynamics: plan for strategies to monitor and support team dynamics, especially in asynchronous tasks. This might include requiring teams to keep meeting minutes or having formative assessment points to provide feedback on team performance.

- Peer assessment: consider incorporating peer assessment as part of the evaluation process, deciding on its weight in the overall assessment and how it will be implemented to ensure fairness and student involvement in the assessment process.

Getting started

If you have not considered why you are going to use teamwork then please consider reviewing the “When and why use teamwork?” found the the 'Teamwork 101' section.

Setting up team tasks

In designing a teamwork task the following checklist may prompt some consideration:

- What is the teamwork task?

- Why are we doing it?

- Where will the teamwork task happen?

- When does the work need to be completed by

- How will teamwork be managed and assessed?

- Duration of project/experience and expectation/capacity to engage.

- Focus of task brief & deliverables*

- Where will this take place?

- What resources/support/facilities are needed - is this feasible?

- Is the task extra-curricular or credit-bearing - if so, what %?

- If assessed, will the output be co-produced or e.g. an individual reflection on teamwork?

Assessing Teamwork

If you plan to assess your students and require them to submit evidence to be marked electronically and incorporate peer assessment via BuddyCheck, please adhere to the following guidance.

If you do not require the similarity report offered in TurnItIn, it is strongly recommended that you create your teamwork assignment using Blackboard Ultra Assignments and NOT TurnItIn.

Using Ultra Assignments will allow a student to upload the teamwork evidence on behalf of the group (as in Turnitin) however when this work is marked the grade is automatically shared with all other group members. In TurnItIn, this does not happen and requires manual input which will be repetitive, time-consuming and high risk of human error when handling data.

Using a Blackboard Ultra Assignment portal also streamlines the process of adding student grades into the Gradebook. For BuddyCheck to work and provide individual scores based on peer evaluations, each student must have the ‘shared group grade’ against their name in the Gradebook.

How will students be allocated to teams?

It is not simply a case of allocating students to teams and asking them to work collaboratively without guidance can create immediate tensions and concerns. This might be the first teamwork experience for some students, perhaps there was a bad prior experience, there could be concerns over the group members, or difficulties working with others. There is a lot to consider but firstly they need to be put into groups. It can be useful to think about some of the challenges as you look at the list of options below (there are of course more):

- You choose (pre-selected groups): Students are put into groups by the course leader. There are various ways that this can be done: random selection (various approaches to this), according to interests (declared), characteristics deemed relevant to create balance and diversity.

- They choose: Students self-select. This can be done according to who they want to work with or perhaps an area of interest.

- Allocating teams according to roles. As an example team work might consist of a project that has several key roles. Students can put themselves forward to take on that role. Building on this, some projects will rotate roles, so that every person plays a part in any given role.

- Other options might exist! We welcome your examples of practice, please share via this Microsoft Form.

There is no ‘right’ approach - it can also be useful to try out, and reflect on the different approaches to see how each of these work in practice. For further support on how to create groups within Blackboard Ultra, please visit this page: Communication - Ultra Essentials (cardiff.ac.uk)

Managing team numbers

Team working can in itself be an approach to managing a large cohort but when creating or allocating teams you will need to consider group numbers. Deciding on your approach might very well depend on the size of your cohort and what is manageable.

- How big is the cohort?

- Does it easily split into groups of 4 or 5?

- How many groups will this leave you to manage?

- Is this doable?

- Do you have any support?

Team sizes

- Working in pairs

- Optimal size for groups

- How large is ok?

- How to manage large groups

Ways of assessing teams

Many academic staff avoid using teamwork as an assessment tool due to the perceived difficulty of creating a fair and individualised mark. However, if set up correctly, the benefits of learning far outweigh these challenges. For these reasons, the ability to generate a fair, individualised mark, which recognises individual contributions, is key to underpinning a good teamwork assessment.

Marking

- What will be assessed?

- When will it be evaluated? Is it a final product/project or will it be assessed over a period of time?

- Are the students going to be assessed on the final product, the teamwork process, or a combination of both (Dijkstra et al., 2016; Kennedy 2005)?

- How will marks be allocated? Will it be a shared team mark, a team average or marks for individual component parts?

- Is your approach just and fair?

Peer assessment

This is a process where students evaluate the contributions and performance of their peers in a group or team-based task. This approach encourages students to engage critically with the work of their colleagues, fostering a deeper understanding of the subject matter and the development of evaluative and feedback skills.

- Will you use peer assessment as part of the assessment process

- What percentage will you use for peer assessment

- Will you involve students in the decision-making?

Considering how the teamwork task will be assessed is a key component of designing the task. One of the first challenges is to decide whether the students are going to be assessed on the final product, the teamwork process, or a combination of both (Dijkstra et al. 2016; Kennedy 2005). You must also consider how marks will be allocated – will it be a shared team mark, a team average or marks for individual component parts?

The key questions students will focus on are what will be assessed, when and how will it be evaluated, and who will be assessing it. Having clarity on these questions can go a long way to alleviating a number of the potential pitfalls of teamwork and reassuring our students that they will receive a valid and fair mark for their participation in teamwork tasks.

You should also consider who will apply the assessment criteria, it could be students, tutors, or both. Individual contributions can be considered through a weighted mark through peer evaluation, or through each member contributing an individual section to the teamwork task. But how can you measure individual contributions to the final product?

In the case of synchronous tasks, this is perhaps less challenging as tutors can observe interactions and team dynamics and monitor student contributions. The challenge increases when work is carried out asynchronously, and then this can become difficult to monitor, in which case peer assessment of contribution may be a more appropriate strategy. There are, however, alternative ways that asynchronous contributions can be recorded. Teams can be asked to keep minutes of meetings and submit these as a part of the assessment at regular intervals. This is particularly effective at monitoring student participation with the task and can be a means to try and assist or re-engage students who are not contributing. It can also be helpful to have two assessment points, one formative mid-way through the task and one summative at the end of the task, to provide feedback to team members on how they are perceived within the team. However, the students working within a team are often in the best position to assess the contributions within their team, and this can be harnessed through peer evaluation of their contribution (Hanrahan and Isaacs 2001).

With asynchronous teamwork tasks, the tutor can restrict their marking to the quality of the product rather than the process and contributions. This option, which probably most closely reflects the real world, gives one to all team members; however, this can create issues of fairness within the team where students may resent sharing marks with students they perceive to have contributed less time on task. Alternatively, individual marks can be allocated to each member, but that would require clear identification of each member’s contribution.

Using peer assessment

Including an element of peer assessment within a team task can help students get involved with team tasks and contribute to a greater sense of marking fairness. BuddyCheck has been trialled within Cardiff University to support peer assessment of team tasks, in which students received individual marks based on an initial team mark combined with peer evaluations, 72% of students agreed that having an individual mark was fairer than just a team mark.

Including an element of peer assessment within a team task can help students get involved with team tasks and contribute to a greater sense of marking fairness. BuddyCheck has been trialled within Cardiff University to support peer assessment of team tasks, in which students received individual marks based on an initial team mark combined with peer evaluations, 72% of students agreed that having an individual mark was fairer than just a team mark.

Following the successful trial, this system is now available to all and is fully supported. Further information about this tool is available via the Intranet.

To provide a fairer individual mark to students, BuddyCheck takes the initial team mark provided for the student and then combines this with self and peer evaluation scores in several key areas based on the CATME Framework, and/or customised questions designed by the tutor. Once the peer evaluations have been completed, BuddyCheck then offers an adjustment factor to provide individual students with their own personalised scores and feedback, which links directly into GradeBook within Learning Central.

Furthermore, the tool offers a range of functions that can be used to help ensure marks are seen as fair. For example, it allows tutors to mitigate against potential bias either for or against other group members, with its ability for lecturers to view results, comments and feedback labels attached to each student to allow for the moderation of the peer evaluation. Similarly, it offers tutors the ability to detect team conflicts through its ‘Feedback Labels’ feature, which allows tutors to better identify conflicts in the team dynamics, highlighting any skews in the peer evaluation results provided.

Monitoring and support

Key points

- Engagement and contribution monitoring: establish methods to track individual engagement and contribution within the team, considering the role of these metrics in assessment.

- Team dynamics support: plan for supporting teams where students are not engaging and decide on the consequences for non-engagement. Include contingencies for extenuating circumstances affecting team members.

- Task and module design integration: ensure the group task aligns with module learning outcomes and graduate attributes. Verify the fairness and equity of the task compared to individual tasks.

- Teamwork skills development: prepare students for teamwork through introductory workshops, discussions about team dynamics, and guidance on handling challenges in teamwork.

- Feedback and reflection encouragement: Implement regular reflection activities and peer feedback mechanisms to promote continuous improvement and accountability within teams.

- Resource provision and accessibility: ensure all students, regardless of their background or situation, can access and benefit from the teamwork task, providing necessary training and resources.

How will progress and contribution be monitored and supported?

The first consideration is whether this is going to form part of the assessed component of the task. If so:

- How will you know if students don't engage? What is your role/capacity to manage this?

- How will you support teams where student(s) are not engaging? What is the consequence of non-engagement?

- What if individuals have ECs? How will this affect summative outputs?

- What if students can’t engage? Is there an alternative?

Are you prepared to be flexible and make adjustments based on the specific cohort, ongoing feedback and challenges encountered by teams?

How does the teamwork task fit into your module design?

- Can you map the learning outcomes to your task?

- Have you created assessment criteria for the teamwork task?

- Can you use generic marking criteria, or do you need to create task-specific criteria?

- How does the task map to the graduate attributes?

Do learning outcomes and assessment criteria relate to the product and/or process of the teamwork task and are these clearly communicated? In planning teamwork, consider:

- Is the task fair and equitable compared to tasks that students could realistically be asked to complete as individuals?

- Can Module Learning Outcomes* be mutually/constructively aligned with a teamwork task, particularly with regard to assessment?

- What to assess as outputs of teamwork; a collaborative or individual artefact or reflection, or the processes, skills, and contribution to teamwork itself?

- Will the specific task or learning outcome be enhanced by teamwork?

- Does the cohort have sufficient experience/knowledge/skills to collaborate effectively on the teamwork task?

- If the teamwork task provides the opportunity for all students to fulfil the specific learning outcomes, regardless of situation or background?

- Will the teamwork scenario provide an authentic collaborative experience to assist students in gaining essential transferable skills e.g. planning, negotiation, and communication?

[* N.B. If the development of teamwork skills is a learning outcome then relevant training and instruction in teamwork should be provided.]

By considering these factors before introducing the task and being reactive while the task is running, an effective transition to or introduction of team-based assessments can be achieved, ensuring their effectiveness, and creating a conducive learning environment for all students.

Scaffolding the task

Scaffolding the teamwork task is critical, it is not sufficient to merely assign students to teams and expect them to understand how to work effectively in a team environment as they may lack the skills to work effectively in a team before starting the task (Shimazoe and Aldrich 2010).

Do students know how to work in teams?

Effective team-based learning requires teaching students how to work collaboratively, which is a skill in itself. This process involves guiding them through the various stages of team development, from ‘forming and storming’ to ‘norming and performing’. This guidance is an essential step, regardless of whether team dynamics are formally assessed.

There are guidelines on the intranet that can be used to structure an introductory session students need to prepare for teamwork. There are many reasons why students might feel worried and unsure about teamwork. This might be the first time for some students. Some will be concerned about working so closely with others. Others might be concerned about practicalities or the impact on their marks. There will be students with competing demands on their time, both personally and professionally, and this can lead to feelings of anxiety when faced with team working.

How will you prepare students for teamwork?

- Introduce students to teamwork

- Discuss the challenges and benefits of teamwork

- Signpost guidance in student intranet (Working in groups - Working in groups (cardiff.ac.uk))

- Make team expectations clear

- Ensure students are aware of their individual responsibilities

- Discuss what to do when things go wrong

- Discuss what to do when ex-circs are needed

- Introduce the task and invite questions

When scaffolding the teamwork task consider some, or all, of the following:

- Introductory workshops

- conduct sessions on team dynamics, communication skills, and conflict resolution.

- flag up other resources for enhancing teamwork skills (other university resources etc.)

- Role allocation guidance:

- Explain the rationale for the approach to the selection of teams

- provide frameworks for assigning roles based on strengths and learning needs.

- Consider how you will evidence of contribution or participation

- Project management software/peer assessment

- Project management training: teach basic project management skills, including time management and task delegation.

- Regular reflection activities: encourage students to reflect on their team experiences and learn from them.

- Guidance on how to reflect needed

- Team contracts: facilitate the creation of team contracts to establish ground rules and expectations (Pokorny and Warren 2016).

- Peer feedback mechanisms: implement structured peer feedback to promote accountability and continuous improvement.

- Facilitated group discussions: hold moderated discussions to help teams navigate challenges and celebrate successes.

- Progress monitoring tools: use tools like Gantt charts or task lists to track progress and adjust plans as needed.

- Conflict management strategies: Teach and provide resources for effectively managing conflicts within teams, including how and when to ask for help.

By integrating these strategies, academics can effectively scaffold teamwork tasks, ensuring that students not only achieve the task objectives but also gain valuable skills in teamwork and collaboration. It should be noted that there is no one-size-fits-all framework as each team-based task will be different and each group will have different dynamics, which need to be considered.

How will you support team dynamics?

Will all students have the opportunity to contribute equally?

- What determines team size and makeup?

- How experienced, knowledgeable, and equipped are the cohort to work together/without close supervision?

- What support and/or training is needed (outset and ongoing)?

- Will individual student inputs be visible (to educators)?

- How will students be held accountable? Will management and organisation of teams be self-led or managed structures e.g. roles or self-directed collaborative practice

Extenuating circumstances

Guidance on managing the Reasonable Adjustment and Extenuating Circumstances policies for students working in teams, and on implementing regulations on fails and resits in summative assessments involving team working, has now been approved by ASQC.

Guidance on Applying Regulations and Polices to Team/Groupwork

This guidance has been developed with reference to the following regulations and policies:

- Extenuating circumstances

- Resits

- Non-engagement

- Reasonable adjustments

This guidance should be applied to the following situations:

- Where a team of students is assessed by a single piece of work produced jointly by the team or group, whatever the format. This is a more authentic form of assessment than assessing students on team or group work individually but requires student teams to be effectively supported.

- Where students are assessed by individual assignments that demonstrate learning that has come from work undertaken as part of a formal team or group, and where the quality of individual students’ outputs will be affected by the effectiveness of the work done by the team as a whole (eg: collaborative lab work; data collection).

Troubleshooting

I tried it and it didn’t work!

Encountering difficulties when first implementing team-based assessment is not uncommon, and it’s important to view these experiences as valuable learning opportunities. Here are some encouraging strategies to address common pitfalls:

- Reflect and Identify Issues: Take time to reflect on what didn’t work and why. Was it group dynamics, unclear instructions, or assessment challenges?

- Seek Feedback: Ask students for their input on what they found challenging and what could be improved.

- Adjust the Approach: Based on feedback, make necessary adjustments to the task design, assessment criteria, or support structures.

- Start Small: Consider scaling back the complexity of the task or reducing the weight of the team-based assessment in the overall grade.

- Enhance Guidance and Support: Provide more detailed guidelines, additional resources, or workshops on teamwork skills.

- Peer Learning: Encourage the sharing of best practices among colleagues who have successfully implemented team-based assessments.

Remember, setbacks are part of the journey to successful implementation. With each iteration, your approach will evolve, leading to more effective and rewarding team-based learning experiences.

Potential issues

When introducing team-based tasks, it is perfectly natural to encounter challenges, but these can be effectively overcome with the right strategies and a positive approach. Remember, each challenge presents a learning opportunity for both students and staff, which will help you refine teamwork for future cohorts.

A non-exhaustive list of some potential challenges and strategies to mitigate them are:

| Potential Issues | Strategy |

| Communication Breakdown | Foster open communication and provide training in effective communication skills |

| Uneven Work Distribution | Implement peer feedback mechanisms and regular check-ins to promote balanced participation |

| Conflict Among Team Members | Equip students with conflict resolution skills and establish clear conflict management protocols |

| Lack of Engagement or Motivation | Use supportive feedback and celebrate team successes to boost motivation |

| Difficulty Adapting to Team Dynamics | Conduct workshops on team dynamics and encourage peer support systems |

| Task Misalignment with Objectives | Regularly review and adjust tasks to ensure alignment with learning objectives. |

| Inadequate Problem-Solving Skills | Provide problem-solving training and scaffold tasks to develop these skills |

| Assessing teamwork where members report poor or non-engagement by another student* | Adjust the total shared mark by a peer-assessed weighting e.g. 20%. The extent of this weighting could be co-created with the students at the outset. Students could also be supported in co-creating a code of conduct to set out expectations for engagement |

*Unless mark schemes specifically allocate marks for attendance at group meetings and identify measurable markers of engagement in group activities, marks should not be deducted from students who have not (fully) engaged other than through the peer assessment process.

By proactively addressing these issues with the corresponding strategies, staff can transform potential setbacks into powerful learning experiences, enhancing the overall effectiveness of team-based tasks.

![]()

Feedback and closing the loop

As with other forms of assessment, student (and staff) feedback serves as a vital tool for refining and enhancing the teamwork process. Feedback should be used strategically to identify areas for improvement and make informed adjustments to task design, support mechanisms, and assessment strategies. By effectively closing the loop, educators can ensure that each iteration of the teamwork process is more aligned with educational objectives, responsive to participant needs, and conducive to a richer learning experience. The following provides practical steps for utilising feedback to enhance future iterations of team-based activities, fostering a co-creative and dynamically evolving educational environment.

Key points

- Gathering feedback: how will feedback from both students and staff be gathered? Some approaches could include surveys, focus groups, or reflection sessions, aimed at capturing diverse perspectives on the teamwork process.

- Reflection and analysis: encourage and facilitate reflection on team activities, both during and after completion. Analyse feedback to identify common themes, successes, and areas needing improvement.

- Future planning: use the insights gained from feedback to inform the planning of future team-based activities. This might involve adjustments in task design, support mechanisms, and assessment methods to better meet the needs and preferences of participants.

- Co-creation: engage students and staff in a co-creation process, where their feedback directly influences the design and execution of team-based tasks.

Soliciting Feedback

- Identify areas for improvement: use feedback to pinpoint specific aspects of the teamwork process that need refinement, such as communication channels, role distribution, or assessment methods.

- Incorporate student (and staff) insights: integrate insights from both students and staff to gain a comprehensive understanding of the teamwork experience from multiple perspectives. Share feedback between cohorts to help them prepare for the task ahead.

- Adjust task design and objectives: modify the design and objectives of team tasks based on feedback to better align with learning outcomes and student capabilities.

- Enhance support and resources: based on feedback, provide additional support and resources where needed, such as workshops on teamwork skills or clearer guidelines for team projects.

- Refine assessment strategies: tailor assessment strategies to address any issues raised in feedback, ensuring fairness and transparency in the evaluation of team contributions.

- Facilitate co-creation: encourage co-creation of teamwork activities with students, allowing them to have a say in how team-based tasks are structured and assessed.

Co-creation

Collaborative co-creation harnesses both the pedagogical expertise of staff and the diverse perspectives of students. Through the exchange of ideas, feedback, and innovative approaches, co-creation can continuously improve the design, execution, and assessment of team-based tasks. The following points offer some potential ways in which the student perspective can be harnessed.

- Active co-creation of learning objectives: engage both staff and students in jointly setting the learning objectives for team tasks to ensure they are relevant, achievable, and aligned with broader educational goals.

- Feedback mechanisms: implement regular and structured feedback sessions where students can express their experiences and suggestions, and staff can provide constructive feedback on teamwork processes and outcomes.

- Reflective practices: encourage students to participate in reflective activities, such as reflective journals or group discussions, to share insights about their teamwork experiences, which staff can then use to inform future task design.

- Peer-to-peer learning opportunities: facilitate environments where students can learn from each other's experiences and strategies in teamwork, potentially through peer-led workshops or discussion forums.

- Iterative task design: collaborate with students to iteratively design and refine team tasks, ensuring that each iteration takes into account the feedback and learning from previous experiences.

- Joint assessment development: work with students to co-develop assessment criteria and methods for teamwork tasks, ensuring transparency and a shared understanding of expectations and outcomes.

- Make clear to students if task design is shaped by industry practice. Consider ways in which co-creation be used to reflect on current and future working practices.

Deeper Dive

Cardiff University Case Studies

From an unsuccessful first attempt through to an equitable assessment

During my first attempt at introducing teamwork, I made every mistake possible, as a newly appointed academic I did not know any better and no guide like this existed to help me. So I took the “Nike Approach”, put students into groups, gave them their topics and told them to “Just Do It”. I sat back and was horrified by the number of emails I received from students complaining about the task’s lack of clarity, their teammates, or the fact that their marks were being influenced by their peers.

Over several years, I made small, incremental changes, listening to the student feedback to reach the point where in the final two years of running the team-based assessment only one issue was flagged with a student not participating in the task. On further investigation, the student was discovered to be struggling with mental health issues, which allowed for an earlier support intervention.

The first change was to introduce an individualised element to the assessment mark, so 60% of the mark was for the individual contribution and 40% for the overall group dynamics. As a byproduct of this change both the process and product were being assessed, so pre-task workshops were introduced to teach students how to work effectively in teams and to manage conflicts. As part of this workshop teams were asked to negotiate a team contract, which outlined expected behaviours (Whatley 2009).

Given that the process was now being assessed a mechanism for recording participation and contributions was needed. The first attempt at recording this was to simply ask teams to keep a diary of meetings with attendance and agreed contributions. This diary was then emailed by a member of the team on a fortnightly basis. A concern with this approach was that only one member of the team emailed the diary, so there was no way of validating whether the emailed version was the same as that agreed by the team. Therefore, the emailed diary was replaced by a team wiki, which allowed for backtracking through the entries to map student contributions.

In an ideal world, students would be able to manage conflicts, however, on occasions, there may be a need for academic intervention. Lejk, Wyvill and Farrow (1996) proposed a yellow and red card system, whereby team members were able to request a yellow card for a non-participating member. The academic can then review the contribution of the named student, arrange to meet with that student to ascertain any mitigating reasons for being unable to participate and if upheld, issue a yellow card as a warning to the student. If a student is given a yellow card, then they are in danger of losing a percentage of their marks for the task; however, if the student makes a fair contribution to the task, then the card can be rescinded to allow full marks to be achieved. If the team reports no change in performance, a red card can be issued, following academic investigation, resulting in the non-participating team member being removed from the team and receiving a mark of zero. This has the effect of not disadvantaging the remaining team members in the final task as the team and academics can discuss ways to overcome the loss of a team member.

Finally, peer-to-peer evaluation was incorporated. Students working within the team are well-placed to judge the contributions of their team members (Hanrahan and Isaacs 2001). WebPA was introduced to allow members of the team to anonymously rate the other members and is a powerful tool to provide insight into the team dynamics whilst also encouraging students to reflect on the teamwork process as a whole (Gordon 2010). BuddyCheck was not available at this time and will automate many of the processes that were manually carried out using WebPA.

Share Your Case Studies

We would like to invite fellow staff to share information surrounding any experiences of using Teamwork within their learning and teaching practice. Please use the Microsoft Form below to share a summary and any relevant supporting documents.

References

Dijkstra, J., Latijnhouwers, M., Norbart, A., & Tio, R. A. (2016). Assessing the “I” in group

work assessment: State of the art and recommendations for practice. Medical Teacher,

38(7), 675–682. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2016.1170796

Francis, N.J., Allen, M, and Thomas, J. (2022). Using group work for assessment – an academic’s perspective. Advance HE.

Gordon, N. A. (2010). Group working and peer assessment — using WebPA to encourage

student engagement and participation. Innovation in Teaching and Learning in Information and Computer Sciences, 9(1), 20–31.

https://doi.org/10.11120/ital.2010.09010020

Hanrahan, S. J., & Isaacs, G. (2001). Assessing self- and peer-assessment: The students’

views. Higher Education Research & Development, 20(1), 53–70.https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360123776

Kennedy, G. J. (2005). Peer-assessment in Group Projects: Is It Worth It? In Proceedings of

Australia Computing Education Conference. Newcastle, Australasia.

Lejk, M., Wyvill, M., & Farrow, S. (1996). A survey of methods of deriving individual grades

from group assessments. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 21(3), 267–280.https://doi.org/10.1080/0260293960210306

Mazur, E. (1996). Peer Instruction: A User’s Manual. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Pokorny, H., & Warren, D. (2016). Enhancing teaching practice in higher education. London: Sage Publishing Ltd.

Riebe, Linda & Girardi, Antonia & Whitsed, Craig. (2016). A Systematic Literature Review of Teamwork Pedagogy in Higher Education. Small Group Research. 47. 10.1177/1046496416665221. Shimazoe, J., & Aldrich, H. (2010). Group Work Can Be Gratifying: Understanding & Overcoming Resistance to Cooperative Learning. College Teaching, 58(2), 52–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567550903418594

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society. The development of higher psychological processes. Mind in Society. Cambride, MA: Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13398- 014-0173-7.2

Whatley, J. (2009). Ground Rules in Team Projects: Findings from a Prototype System to Support Students. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 8(1), 161–176. https://doi.org/10.28945/165

Yorke, M., & Knight, P. T. (2006). Embedding Employability into the Curriculum. https://www.qualityresearchinternational.com/esecttools/esectpubs/Embedding employability into the curriculum.pdf. Accessed 21 April 2021

Share Your Feedback

Where Next?

Study Skills: Working in Groups

Explore the 'Courses and workshops for learning and teaching staff' page to discover and book onto courses such as, 'Designing and managing groupwork tasks including an introduction to BuddyCheck'.