Articulating inequalities

Articulating inequalities and privilege including critiquing understandings of the origins of subject knowledge

Within the sector there has been an increasing emphasis on the importance of diversifying, decolonising and implementing an anti-racist curriculum and challenging our unconscious biases in the way we design and deliver teaching.

Below we discuss how these perspectives and approaches can help us reflect on and improve our practice. However, it is worth noting that although we discuss them separately, there are also similarities and overlaps between the approaches.

Diversifying and Decolonising the curriculum and critiquing understandings of the origins of subject knowledge

Much literature has been written on diversifying and decolonising the curriculum with many perspectives on what each term means.

At Cardiff University we acknowledge these differing viewpoints and value the varying perspectives. The following section draws holistically on the literature of both diversifying and decolonising pedagogies, appreciating the interwoven principles that acknowledge the need to diversify, identify, critique and dismantle existing origins of knowledge from an ethnocentric perspective.

“Decolonising the curriculum interrogates the ongoing impact of legacies of colonisation and imperialism on knowledge production. A decolonial approach concerns itself with deconstructing existing hierarchies, in favour of drawing on multiple knowledge systems/ways of knowing in order to integrate a range of perspectives, with a particular focus on amplifying the voices currently underrepresented in the curriculum” (UAL 2023: 3).

Disciplines that are part of the academy have not been immune to the process of colonisation. How we gain an understanding of the world is grounded in cultural world views that have either ignored or been antagonistic to knowledge systems that sit outside those of the colonisers. Our research and teaching methodologies, all instruments of knowledge production, are also used as ways to classify, organise and represent knowledge.

Some have expressed concern that decolonising the curriculum is about dismissing or deleting what has been: But decolonising is not about deleting knowledge or histories that have been developed in the West or colonial nations; rather it is to situate the histories and knowledges that do not originate from the West in the context of imperialism, colonialism and power, and to consider why these have been marginalised and decentred (Arshad 2021). Paying attention to representation and decolonising the curriculum is a major focus in many Higher Education institutions.

There is great guidance from University of Arts London which can aid your reflections on this significant issue in inclusive education.

SOAS have produced a helpful toolkit, watch the video below from SOAS, and read the Case Study (OU 2018), or read more about De Montford’s project on decolonising the curriculum.

Arshad (2021) suggests a number of stages when approaching decolonising:

-

- Develop understanding of why decolonising the curriculum is important

- Examine our own subject discipline to identify if there are alternative canons of knowledge which have been marginalised or dismissed as a result of colonialism

- Ensure a range of voices and perspectives are represented and ways you might re-conceptualise the curriculum to reflect wider global and historical perspectives.

- Consider the diversity of our student groups and ensure learning content moves beyond Western to global frameworks.

- Diversifying the reading list has been one route that many have chosen as a quick way to begin the journey of decolonising the curriculum. There is subliminal value in diversifying the reading list, because it is a way of acclimatising learners to the presence of a range of writers, be that writers from diverse ethnic groups, writers who identity as LGBTQ or other characteristics.

- From diversifying to decolonising: provide opportunities for the students to discuss the historical legacy of colonisation for that subject area. For example, in astronomy when we discuss life, universe, planet and stars, we can open up discussions on how different perspectives might understand these topics. How might different indigenous communities understand and talk about stars? Would it be in the language of exploration and conquest of space or in terms of navigation and survival? (Arshad 2021)

Anti racism pedagogy

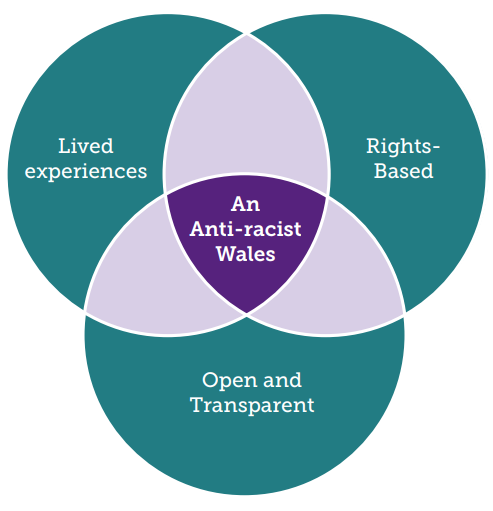

figure1: Anti-racist Wales Action Plan: 2022 | GOV.WALES

There has been acknowledgement of institutional and systematic racism within society since the death of George Lloyd Floyd in 2020 and the Black Lives Matters movement, which ignited a call to action for society as a whole to become actively anti-racist.

Welsh government has pledged to an anti-racist society in Wales by 2030 with a key action for HE of ensuring the experience of all students is equitable, and that racial discrimination and institutional racism is addressed and dismantled. In 2020, Advance HE launched the Tackling Structural Race Inequality in Higher Education campaign. Its purpose was to support UK Higher Education institutions to better ‘understand and address … structural race inequalit[ies] in all aspects of higher education.’

Cardiff University (‘Our future, together’ strategy, 2024) is committed to becoming an actively anti-racist institution by 2030, with much work already underway both across the institution and in engaging with communities across Wales and the sector.

What is an anti-racist curriculum?

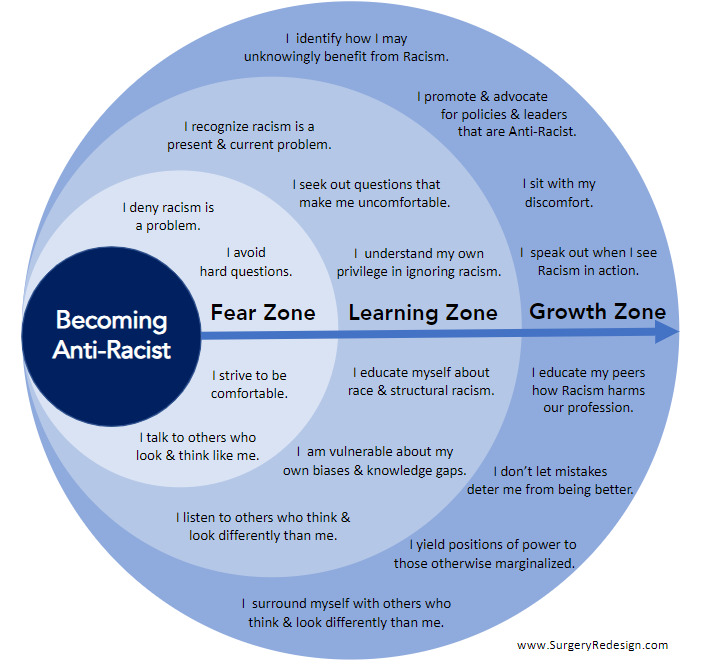

Where decolonising and diversifying the curriculum focus on the need to critically reflect, diversify, question and deconstruct existing hierarchal knowledge systems, anti-racist pedagogy begins with oneself and the importance of reflecting on our own pedagogies, behaviours and beliefs.

When considering what this means for learning and teaching, anti-racist practice focusses on examining our own practices, pedagogies, curriculum and behaviours in order to acknowledge biases and actively implement change. The process of self-reflection is key to anti-racist practice and moves away from simply incorporating racial content in modules and programmes that have a race or ethnicity focus, towards unpicking pedagogies used to teach and research, questioning our own position within the learning environment. (Kendi 2019).When we reflect on our own assumptions and bias and actively engage in antiracism pedagogy, we impact how we design, teach and assess our students with the goal of providing a curriculum that enables all students to engage and grow in their own antiracism journey.

“The only way to undo racism is to consistently identify it and describe it–and then dismantle it.” –Dr. Ibram X. Kendi, How to Be an Antiracist (2019)

Drawing on the work of Kendi (2019), because racism is institutional and systematic, being an anti-racist is an active process of identifying and opposing racism in order to actively change the polices, practice and behaviours and beliefs that perpetuate racist actions. Inclusion is the foundation of good learning and teaching practice but when you view learning from an anti-racist lens you build on best practice and critically examine the who, why and how we are teaching.

Anti-racism pedagogy is constantly evolving, with resources available across the sector that provide guidance on how to develop practice across different disciplines. The Anti-Racist Curriculum Project by Advance HE (2021) Anti-Racist Curriculum Project | Advance HE provides a wealth of guidance on different aspects of an anti-racist curriculum. If you wish to explore more toolkits and guidance from across the sector jump to the Deeper Dive section, below.

When situating your discipline and curriculum using an anti-racist perspective, a key consideration is the need to create safe and brave spaces for staff and students to bring their authentic selves and share their experiences and perspectives. Both will have varied understanding of anti-racism pedagogy, and it is important to acknowledge this and provide opportunities for all members of the learning community to learn and reflect. Below you will find considerations when implementing anti-racism into the curriculum.

Creating brave spaces

Based on the work of Arao, B, & Clemens, K (2013):

- To what extent are teachers and students aware of what might constitute racist or racialising behaviour in a learning context?

These might include manifestations of personal disrespect, such as cutting students off, laughing at them or speaking over them; expecting someone to act as a ‘spokesperson’ for a particular group or view; the stigmatisation of different pathways into education or linguistic skills which may be associated with ethnicity; unconscious forms of bias in terms of recognition, expectations and personal interactions; as well as more obvious forms of discrimination and bias.

- Is there an understanding of how these can be addressed?

- Is space and time given in modules, lectures, seminars and office hours for students to openly acknowledged and confront this?

- Do students have a place to go to discuss these matters?

Learning and teaching practice

- Anticipate how to frame topics related to race and various forms of inequality, as they may be emotionally salient in different ways for students with a range of experiences.

- You might add an anti-racist statement to your syllabus that is authentic to your voice and discuss its implications for your course with your students.

- Consider pausing to reflect and consider if there have been times when you could have been more intentionally or explicitly anti-racist while leading a discussion or class session. To build on this reflection, try regularly gathering feedback from your students to understand their experiences and perspectives.

- Try providing opportunities for students to reflect on their own biases, for example through individual written reflection or small group discussion. Students may have a range of emotional responses, which may mean planning space for them to process those emotions.

- If you’re comfortable doing so, share your own journey with your students as a learner who makes mistakes but continually strives to do better. Like your students, you may need time to process your emotions based on your positionality and experiences.

Language matters

From Advance HE Anti- Racism Curriculum Project

ARC Language Matters Portfolio March 22.pdf

Arbu-Arqoub and Alserhan (2019) suggest the following thoughts and actions to try and overcome misrepresentation.

Unconscious Bias and ‘Epistemic Credibility’

Watch this short introduction to unconscious bias:

Often, educators seek or claim to pursue neutrality and fairness in their teaching. Regardless of good intentions, by pursuing neutrality, educators may be complicit in ignoring existing power dynamics and maintaining inequitable systems. An educator’s assessments of who can learn and who can produce knowledge are influenced by their assumptions about the students, based on their decision to take into account or exclude aspects of their social identities.

In the learning environment, epistemic credibility (or knowledge credibility) is the authority given to a learner to receive and produce knowledge. In other words, epistemic credibility is the authority to be a learner as well as a to be a contributing member in the learning and teaching process (Parsons and Ozaki 2020).

Simply put, educators grant or deny epistemic credibility to their students. They do this consciously or unconsciously, as they gauge a student’s knowledge authority (i.e., how much do/can/should they learn, how much do/can/should they contribute in class). Often, when lacking knowledge about a person, educators may resort to judgments of appearance (for example, the appearance of belonging to affinity groups), even if they are unaware of it. Educators often make these judgments based on what they see, know, or assume about their learners, based on appearance or interactions with them. Being aware of student identities and educators’ epistemic beliefs is fundamental to creating inclusive classrooms (Parsons and Ozaki 2020).

Where Next?

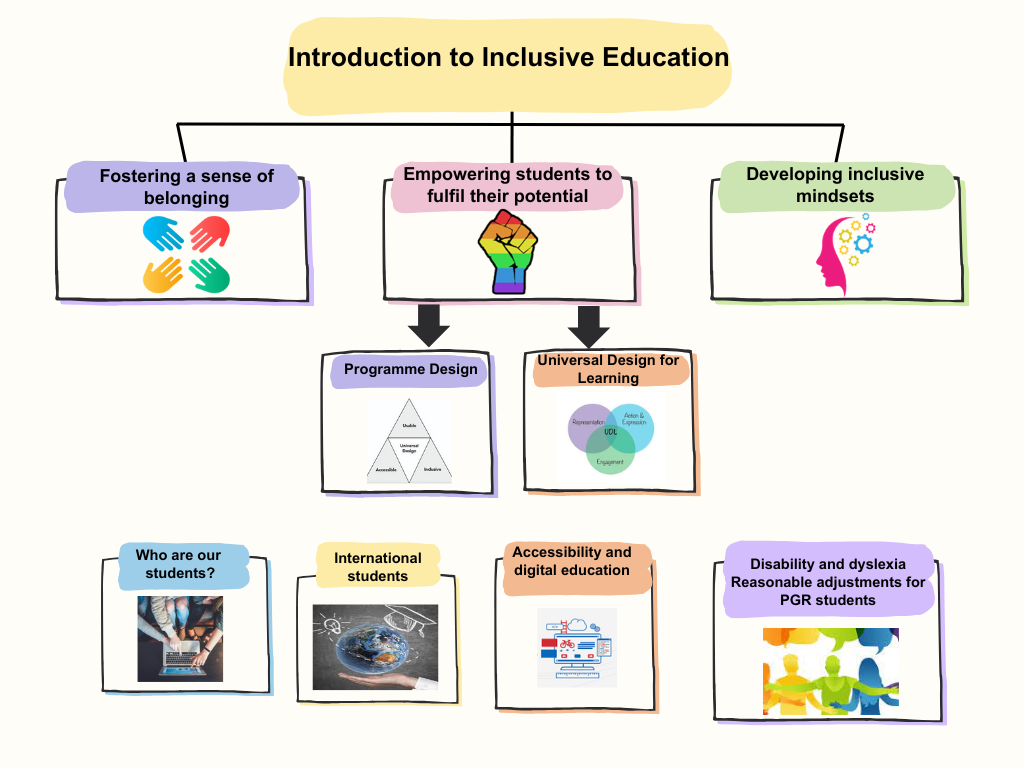

Map of Topics

Below is a map of the toolkit and workshop topics, to aid your navigation. These will be developed and added to in future iterations of this toolkit:

You’re on page 5 of 9 Inclusivity theme pages. Explore the others here:

1.Inclusivity and the CU Inclusive Education Framework

2.Introduction to Inclusive education

3.Fostering a sense of belonging

4.Empowering students to fulfil their potential

5.Developing Inclusive Mindsets

6.Universal Design for Learning