Disability and Reasonable Adjustments

An Inclusivity Theme Page

Introduction

Firstly, some perspectives on disability in university :

1. Conceptualising Disability

Figure: The nine protected characteristics in the Equality Act 2010

The UK Equality Act (2010) defines the nine protected characteristics illustrated in the figure above, and also defines disability:

You are disabled if you have: a physical or mental impairment that has a ‘substantial’ and ‘long-term’ negative effect on your ability to do normal daily activities. ‘Substantial’ is more than minor or trivial; ‘long-term’ means 12 months or more.

The Equality Act 2010 applies to all sectors of education, including Higher Education, and defines our responsibilities to provide accessible, anticipatory education for all (see the Supporting Disabled Students section, below).

Models of Disability

How we conceive of disability will impact how we design and deliver our teaching, and how we respond to disabled students in Cardiff University. There is a vast literature on Disability Studies, which has developed as a discipline alongside new ideas about the nature of disability since the 1970s. The two key concepts are explored below, with further detail and models in the Deeper Dive Section, at the end of the page, should you wish to deepen your understanding. You can also read a summary of the developments in Dan Goodley’s Disability Studies book (2017), in the reference list.

The Medical Model of disability is prevalent in the UK, and conceives of disability as intrinsic to the individual, caused by physical, sensory or medical impairment, and a ‘condition’ in need of treatment. This leads to medically-dominated provision of services, based around diagnoses, with an aim to ‘normalise’ individuals through therapeutic intervention.

The Social Model of Disability challenges these medicalised assumptions, and suggests that while impairment is the condition, such as lacking a part or all of a limb, having a defective limb, organ or part of the body, disability is identified separately, being defined as ‘the disadvantage or restriction of activity caused by contemporary social organisation which takes no or little account of people who have impairments and thus excludes them from the mainstream of social activities.’

Disability and Higher Education

If we apply the social model to higher education, we can appreciate that disability is created by the traditional processes, procedures and practices of learning, teaching and assessment. It is also created by our organisational processes and methods of communication.

These processes, procedures and practices create barriers to learning and attainment for our disabled students. For example a requirement for a diagnosis or assessment prior to an adjustment to teaching practice or assessment would be an illustration of the medical model, whereas flexible, inclusive or universally-designed learning would be an example of the social model.

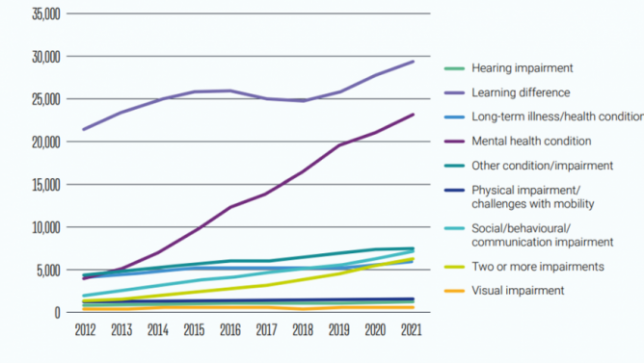

UCAS (2022) completed a detailed study of disabled students in higher education, tracking the changes to the population since 2012. They found:

- Issues in under-representation: one in five working-age adults in the UK are disabled, compared to one in seven HE students

- The most prevalent category: more than a third (35%) of disabled applicants shared a learning difference (e.g. dyslexia or dyscalculia) – the most commonly shared category, representing 5% of all UK applicants

- Significant changes in the needs of students: Since 2012, the greatest increases in people feeling able to share their needs have been seen for mental health conditions (+453%) and social, behavioural or communication impairments (+249%).

Figure: Numbers of disabled students by category 2012-2021 (UCAS 2022)

Similarly, in Cardiff University, the number of disabled students has risen over the last 5 years. Cardiff University Staff can find data on Disability and Reasonable adjustments here.

Thus an effective, supportive approach to our students who are disabled is crucial, to ensure we remove barriers to learning and ensure all students can achieve their potential.

Listen to the experiences of one of our students here: Breaking Barriers: Alexandra Wilson-Newman

There is extensive further research on the gaps, experiences and outcomes for disabled students: to explore more, read the Research Findings on Disability and Higher Education section, in the Deeper Dive, at the end of the page.

2. Supporting Disabled Students in Cardiff University: Legislation, Policy and Practice

Higher Education Institutions have a duty under the Equality Act 2010 to prevent discrimination, harassment, and victimisation. A recent large scale research report identified that only 36% of students who have had any support approved by their university have all that support put in place (Disabled Students UK 2023).

Where it might put disabled students at a substantial disadvantage, we have a legal duty to existing students, applicants, and former students to make reasonable adjustments to:

- provision, criterion or practice

- physical features of the building or premises and

- information, to ensure it is provided in an accessible format.

The duty is anticipatory and continuing, regardless of whether you know that a particular student is disabled or whether you currently have any disabled students. You should not wait until an individual disabled student approaches you before you consider how to meet the duty (EHRC 2014).

There are therefore two approaches to meeting the needs of disabled students:

A. Inclusive Learning and Teaching

B. The legal obligation to meet identified Reasonable Adjustments for individual disabled students.

A. Inclusive Learning and Teaching

Inclusive education requires a continuum of supports that reaches from the classroom to support services, and which incorporates the provision of reasonable adjustments. We need to consider firstly the bottom layer, our universal design of teaching, and then our signposting and interaction with the higher levels.

Figure: UDL and the Continuum of Supports (AHEAD 2023)

LEVEL 1: THE MAJORITY OF STUDENTS: With the incorporation of inclusive education principles into the mainstream practice of the institution, the majority of students can have a successful learning experience without additional support.

LEVEL 2: STUDENTS WITH SIMILAR NEEDS: In some cases, students with similar needs who required additional support can have support provided in a group setting. Examples of this would include group learning support sessions for mature students, and examinations in alternative venues for students needing extra time or a quiet environment.

LEVEL 3: INDIVIDUAL ACCOMMODATION: Individual accommodations or adjustments remain a very important part of an inclusive institution. Some students require individual supports such as Assistive Technology or flexibility with examination deadlines which enable them to participate fully in the learning experience.

LEVEL 4: PERSONAL ASSISTANT: Sometimes students might have the need for more personal, professional supports, in addition to individual accommodations like those outlined in Level 3. For example, students with certain disabilities may require the use of a personal assistant on campus, or, in an exam setting, a reader or scribe.

So what can you do? Inclusive Practice

Start with inclusive, universal design: what can you do to make changes to your practice that are available to all students?

Whilst reasonable adjustments are a legal obligation under the Equality Act, using inclusive approaches benefits all. For example:

- providing all resources such as PowerPoints, documents or readings 48 hours in advance may be a reasonable adjustment for a student with dyslexia, but will also help those with English as an additional language

- providing recordings of the session may be a reasonable adjustment for students with a condition causing problems with note-taking or attendance due to disability, but will also support those who cannot attend due to short- or long-term health conditions, and those with caring responsibilities or employment.

Using inclusive approaches for the whole cohort also benefits us: where we provide universally, less time is taken in the administration of individual requirements, and the crisis-management of individual issues.

Cardiff University Reasonable Adjustments

Take a look at this snapshot of Cardiff University reasonable adjustments from December 2022

If we follow just these five core practices for inclusive education, our numbers of reasonable adjustments would be significantly reduced!

Top Tips: Five Core Practices for Inclusive Education:

- Provide all resources for the session 48 hours in advance via Ultra, including PowerPoints and documents

- Record all lectures, and enable students to audio record sessions.

- For seminars or other active sessions, provide notes in Ultra, or ask students to summarise discussions or activities.

- Provide coherent reading lists which are accessible in advance, have literature easily available online or in Ultra, and which indicate which are essential, desirable and ‘other’ readings

- Be aware that some of your students will have medical needs which may mean they may not be able to attend, or may need to leave sessions early

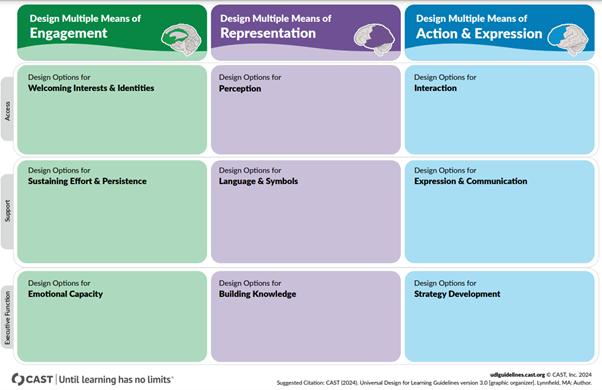

When considering making our practice inclusive, we could use the approach of Universal Design for Learning (UDL), which creates a learning environment designed for a diversity of learners, rather than retrospectively making adaptations to accommodate specific students. UDL builds flexibility in the core curriculum through multiple means of representation, action and expression and engagement.

Figure: Universal Design for Learning (CAST 2024)

You can read more about Universal Design for Learning on this toolkit page

Try this exercise to develop your skills in designing for inclusive practice, before clicking to reveal the model answer below.

Model Answer (click to reveal)

Teaching Guidance Document for all staff teaching on Module X

To meet the needs of our students we need to consistently design and deliver our teaching inclusively, being responsive to identified reasonable adjustments. Please follow this guidance to ensure we meet our responsibilities.

Learning materials and resources

- Make all PowerPoints or other visual aids, reading materials or any other information available at least 48 hours in advance of the sessions to all students.

- Record your session and upload as soon as possible to the Ultra page, under the section for the session, for all students. If this is not possible, for example in seminars or labs, provide notes or ask students to provide summaries, and upload after the session

- Provide a targeted reading list for each session before the module commences, ensuring the texts are available in the library, online where possible: 1-2 short essential readings, plus recommended and extended readings.

- In Ultra, use a range of formats for information: for example provide a short video summary of texts, or link to YouTube or podcasts or other audio material (to provide multiple means of representation)

Guidance for Delivery of Teaching

- Be aware of engagement: design your session with 15-20 minute segments followed by a change in activity. Allow 1 minute silent thinking times. Give choice of topic, and offer variety in mode of responses from student activities (for example, feedback to the group orally, or type your answer into mentimeter) ( to provide multiple means of engagement)

- At the beginning establish ground rules: that you welcome audio recording; that questions can be posted on a mentimeter, or saved for the end of the session; that students are free to move around or leave if necessary but please keep disruption to a minimum; that discussions should respect opinion and diversity.

- Give a session outline or timetable

- Be aware that one student may arrive late to the session, and requires a wheelchair space: contact me if there are challenges and I will contact time-tabling. Organise the students so that they can work in groups – do not leave this student isolated at the front.

Assessment

- Whether your assessments are formative or summative, ensure that you and the marking team are aware of those students who have reasonable adjustments for disabilities affecting expression, and that you discount criteria for expression in your marks, as this is not a core competence for this module. See the Reasonable Adjustments: Guidance for Teaching staff on this page for more detail.

- Provide options for topic, task or mode (to provide multiple means of engagement).

- In your feedback, whether written or verbal, be conscious of your language and ensure your comments reflect the learning outcomes, marking criteria and/or guidance for the task (to provide multiple means of action and expression).

B. Reasonable Adjustments

Whilst inclusive practice can meet the learning needs of a large number of students, there will always be some changes to practice that are required to meet the unique specific needs of individual disabled students. For example, access to recordings of lectures is the most common reasonable adjustment, and therefore if this is available to all students, a number of diverse students will benefit, and a great deal of work is saved in administration. Providing paper handouts in large print, however, would only be required if you had a visually impaired student in the cohort.

Making reasonable adjustments to teaching practice, and to the organisation of programmes and assessments, is a legal obligation under the Equality Act 2010. You can find more detail on the Reasonable Adjustment Policy intranet page, which has links to the policy, guidance on inclusive practice and reasonable adjustments for teaching Staff, and those who work with postgraduate research students, and further information.

If you want to learn more, you can sign up for our CPD workshops: Disability, Dyslexia and Inclusive Education; Disability and Reasonable Adjustments for PGR students; Accessibility and Digital Education; and an Introduction to Inclusive Education.

You can also visit our drop-in sessions, if you have questions or queries about the policy, reasonable adjustments in general, or inclusive practice for disabled students.

What support is available for disabled students in Cardiff University?

In addition to ensuring your design, teaching and support of students meets their needs and reasonable adjustments, you may want to support students to access the wealth of services available from the Student Life teams. If you are unsure which service may be of benefit, recommend the student visit the Student Connect team, online or in the Centre for Student Life, who will ensure they reach the correct services.

- Assessment for Disabled Students Allowance (benefit which may fund equipment, increased general allowances, or non-medical support)

- Assessment of learning need and some forms of screening (for example, for specific learning difficulties such as dyslexia)

- Study skills tutors, and specialist tutors (eg for autistic students)

- Student mentoring and peer support

- Access arrangements and reasonable adjustments

- Wellbeing support and Counselling services

- Student Connect Team: one-stop hub for all student needs, based in the Centre for Student Life

3. Focus on Conditions

Individuality and Intersectionality

Before reading on to explore the range of learning needs or impairments students may have, it is important to consider the challenges of labels and categorisation, and their intersection with other aspects of diversity.

Despite an identical label, two students with the same condition will not have the same learning needs, experiences or outcomes. For example, while two students may both be identified as being dyslexic, they will have differing strengths and challenges – one may struggle with spelling, while the other may struggle with organisation and structuring of assignments.

In addition, other aspects of diversity will impact on their interaction with their learning and the university. For example, those who are first in their family to go to university are less likely to understand their rights to adjustments, or to confidently access support, adjustments or accommodations (Bunbury 2020).

Click on the title below to access more detail on each of the range of conditions, which includes consideration of the lived experience of students, key recommendations for teaching strategies for this group, and access to further information.

Neurodiversity

Neurodiversity

Neurodiversity describes the idea that people experience and interact with the world around them in many different ways; there is no one "right" way of thinking, learning, and behaving, and differences are not viewed as deficits. The word neurodiversity refers to the diversity of all people, but it is often used in the context of autism spectrum disorder (ASD), as well as other neurological or developmental conditions such as ADHD or learning disabilities. (Baumer 2021 in Hamilton and Petty 2023)

From a neurodiversity perspective, these differences in the way people perceive, learn about and interact with the world are conceptualised as naturally occurring cognitive variation, akin to biodiversity in the natural environment… (Hamilton and Petty 2023)

Hamilton, L. and Petty, s. 2023. Compassionate pedagogy for neurodiversity in higher education: A conceptual analysis. Frontiers in Psychology Vol 14 Feb 2023. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1093290/full

Neurodiversity therefore is the concept that brain differences are natural variations – not deficits, disorders or impairments. The terms neurodivergent and neurodivergence are now used to describe all people whose neurological differences mean they do not consider themselves to be neurotypical. Neurotypicality is used to describe people whose brain functions, ways of processing information and behaviours are seen to be standard (The Brain Charity 2022).

Autism, dyslexia, dyspraxia, and ADHD are all examples of neurodivergence, although these can also fall under the category of ‘specific learning difficulty/difference’.

Lived Experience

Quotes from Cardiff University Students:

“I can absorb and repeat information back to you, but not in a logical sequence”

“…we often face barriers to confidence, keeping routines, motivation, and getting top grades”

“ I feel like I can’t ask, that I will seem annoying and stupid”

“When you have learning difficulties or dyslexia, you tend to judge yourself a lot more and I was quite hard on myself: I used to get very frustrated...”

“I get accused of daydreaming…but to take in what’s being said, I have to read things 6 times”

Key Recommendations for Teaching Strategies

- Clearly explain what students can expect and what is expected, plus provide a module or session map;

- Establish mutual understanding of what is being spoken and what is being implied;

- Provide a structure for in-person sessions, catch-up via recordings, and independent tasks;

- Use a consistent structure for Ultra pages across modules

- Consider ways to limit sensory overload or hypersensitivity, including planned breaks, quiet areas and silent thinking time

- Offer flexible working hours where possible,

- Consider choice of seating, choice to work alone, and ability to move around

- Allocate tasks based on strengths (eg group work)Name a contact person for consistency and clarity of communication

- Use UDL as a compassionate pedagogy

(Hamilton and Petty 2023)

Lived Experience

Listen to a description of the learning and teaching experiences of three Cardiff University colleagues, which highlight the impact of neurodivergence on learning in the Cardiff University Disability and Dyslexia Resource.

More Information

To read more about neurodiversity, read the NESTLE toolkit for teaching neurodivergent students. You can also access this comprehensive neurodiversity resource, (click here for new tab, or below) created by the Cardiff University Student Disability Service.

You can also access this learning module by Autism Wales , or take the free Open University course, Understanding Autism.

Specific Learning Difficulties (including dyslexia)

Dyslexia is a learning difficulty that primarily affects the skills involved in accurate and fluent word reading and spelling. Characteristic features of dyslexia are difficulties in phonological awareness, verbal memory and verbal processing speed. Dyslexia occurs across the range of intellectual abilities. It is best thought of as a continuum, not a distinct category, and there are no clear cut-off points. Co-occurring difficulties may be seen in aspects of language, motor co-ordination, mental calculation, concentration and personal organisation, but these are not, by themselves, markers of dyslexia. (BDA 2023)

The construct is still poorly understood (Snowling, 2008). There exists a plethora of definitions, leading to a lack of consensus on what dyslexia is and how it is assessed (Ryder, 2016). There is a growing movement towards identifying an individual’s learning difficulties based not on black and white categorical conditions but on dimensional classification allied to personalised provision.

Findings on institutional provision and lecturer perspectives in HE for specific learning difficulties suggest notable differences in the types and consistency of support offered across institutions, which causes huge challenges for students. The most frequently used model is that of relying on additional learning support (ALS), where support is provided outside of the usual contact time, rather than the recommended approach of inclusive education (Ryder and Norwich 2018).

Quotes from Cardiff University Students

“Dyslexia for me means that I’m like a computer system where my brain is the computer, and my hand is a printer, but they are disconnected”

“I decided to pick modules that were more coursework than exams because I felt that I would I do better in written assessments, like coursework because I have time to look over it and read it to understand it."

"I struggle with sentence structures and organizing all my work. When I get to an exam, I almost like throw it all out there and I struggle organizing into a cohesive argument. For an example, last year I took an autumn exam, I answered, I tried to answer one of the questions. I had all the information down there. I had eleven citations in it and I got 48 per cent, a 40 mark. When I went back for feedback, they said that all the information was there, it was really really good. But it wasn’t organized, it wasn’t structured, they couldn’t actually see, see how it flowed.”

Key Recommendations for Teaching Strategies

- Provide clear expectations and a module and session map

- Make resources available in advance

- Record sessions and make available to all (high degree of non-disclosure for SpLD)

- Ensure all resources are accessible, and can be accessed by accessibility software (eg not locked PDF). Follow digital accessibility guidelines.

- Plan for a range of activities and modes (written, oral, individual and group work) to aid concentration

- Enable movement within the session and consider ways to limit sensory overload

- Support and structure the development of physical activity and skills, as well as cognitive development

- Enable choice in modes of expression, for in-class and assessment work

- Allocate tasks based on strengths

- UDL as a compassionate pedagogy

More information

To read more about Dyslexia, Undertake training on Dyslexia Awareness: There is a free Dyslexia Awareness online training module from Microsoft, or read this book: Pavey et al. 2010. Dyslexia-friendly Further and Higher Education.

This book provides a useful guide to academic writing for dyslexic students: Academic Writing and Dyslexia: A visual guide to writing at university (Wallbank 2023).

Or watch this facinating podcast:

Sensory Impairment

Students with a sensory impairment are less prevalent in our Higher Education community (50-100 students per year, in Cardiff University), but it is likely you will teach someone with a sensory impairment during your career. Disabled students with a sensory impairment have specific and in some instances specialised learning needs, and you may need to work closely with the Disability Service to ensure you can meet these needs.

Visually impaired students may have some vision, useful either for close or distance work, even if categorised as ‘blind’. They will encounter barriers to learning in accessing visual materials, for which they may need to use specialised magnification or speech software. They may also encounter barriers in relation to navigating the university environment, accessing physical spaces, or practical tasks.

Students may be deaf, or Deaf: The word deaf is used to describe anyone who does not hear very much. Deaf with a capital D refers to people who have been deaf all their lives, or since before they started to learn to talk. Deaf people tend to communicate in sign language as their first language. For most Deaf people English is an additional language, and understanding complicated messages in English can be a problem (Signhealth 2023). There is a very strong and close Deaf community with its own culture and sense of identity, based on a shared language.

Quote from Cardiff University Student

“It is all in the description, you have to really think about it; how are you describing what is going on visually, in such a way as we can follow and repeat what you are doing? Are we actually following what is being demonstrated or shown, or are teachers assuming you can see the demonstration or slides?”

Key Recommendations for Teaching Strategies:

For Deaf or deaf students:

- Provide all materials at least 48 hours in advance

- Provide a recording of the session

- Check the teaching space has good lighting and a hearing loop and/or use a microphone

- Face the audience when speaking and speak naturally but clearly

- Provide captions or transcripts for all audio, including live and recorded online sessions, and online videos

- If British Sign Language interpreters are used, speak to the person, not the interpreter

- Offer a range of modes of assessment, including an opportunity to present in alternative formats, eg BSL

For visually impaired students:

- Provide all resources at least 48 hours in advance

- Provide Alt Text, and/or an audio-description of graphs, diagrams or images

- Provide a recording of the session with captions or transcript.

- Audio describe demonstrations or provide opportunity for one-to-one training in practical tasks

- Be aware of mobility challenges – ability to move from locations, time and likelihood of lateness

- Follow digital accessibility guidelines, using accessible documents, fonts and background. For more information on digital accessibility, read our Digital Accessibility Toolkit page

Physical Impairments

Students with physical impairments may have difficulties with mobility, manual dexterity or speech. Some might use a wheelchair all or some of the time. They might need support with personal care. Some physical impairments are fluctuating in impact and, as with all disabled students, it is important to talk to the student about what is most useful to them.

Depending on the impairment, a student with a mobility issue or a physical impairment may have difficulty with managing the distance between different learning activities, with carrying materials, or with notetaking, completing practicals or presentations, and may take longer to ask or answer questions.

Students with physical impairments may need a Personal Emergency Evacuation Plan (PEEP) in case of an emergency, which will be recorded in SIMs by your Disability Contact in the School.

Quote from Cardiff University Student

“The most frustrating thing is going into lectures late, and getting looks from lecturers, or students – when I have to rush everywhere, use back doors, find my way into lifts, wait for the one disabled toilet in the break. And then sit on my own at the front, like Billy bloody no mates.”

Key Recommendations for Teaching Strategies:

- Ensure buildings and rooms are accessible for wheelchair users

- Give 24 hours notice for changes to venue

- Check location of wheelchair-accessible spaces including height adjustable tables

- Ensure the student isn’t isolated from peers for active learning– request students sit at the front: put students in groups with peers, not with support workers

- Consider transition and movement around the room for small group tasks

- Allow for time in between sessions, as students may be late – liaise with the student and timetabling.

- Be aware that a physical disability may result in more hospital appointments and or/ ill health

- Discount disability related problems with verbal expression for those with a speech impairment in presentations or oral examinations

- Consider placements, practical tasks or labs, and fieldtrips and ensure fully accessible

Mental Health

There has been a surge in students with mental health conditions over the last 10 years (UCAS 2022; Student Minds 2023)

Findings from research Student Minds conducted in November 2022 identified key themes in relation to students’ mental health, including the cost of living crisis, and wellbeing support. Headline findings:

- 1 in 3 have poor mental wellbeing, according to the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS).

- One quarter of students surveyed said they have a current, diagnosed mental health issue.

- 30% of students surveyed said their mental health had got worse since beginning university.

- 59% of students surveyed said that managing money was a cause of stress ‘often’ or ‘all of the time’ – an increase of thirteen percentage points compared to 2020/21.

- 1 in 4 students surveyed would not know where to go to get mental health support at university if they needed it.

Cardiff has a range of support mechanisms available for students. This padlet brings together a wealth of information for students with issues with mental health and well-being: Mental Health and Communications toolkit

4. Deeper Dive

Section 1: Models of Disability

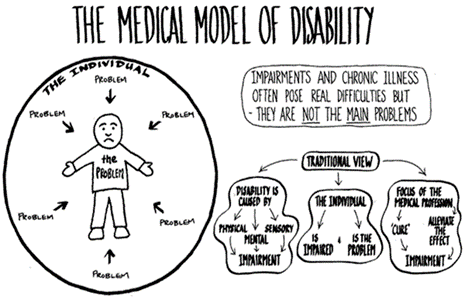

Figure: Medical Model of Disability (IASC 2019)

As summarised in the introduction to this page, the medical model of disability is prevalent in the UK, and conceives of disability as:

- Intrinsic to the individual

- Caused by physical, sensory or medical impairment

- A ‘condition’ in need of treatment

This leads to medically-dominated provision of services, based around diagnoses, with an aim to ‘normalise’ individuals through therapeutic intervention.

Charity, Tragedy or Moral Model

A related understanding is the tragedy model, often used in adverts and fund-raising, where the tragic ‘victim’ is seen as deserving pity and help, or if the person is portrayed as ‘over-coming suffering’, they become the inspiring role-model.

The Social Model of Disability

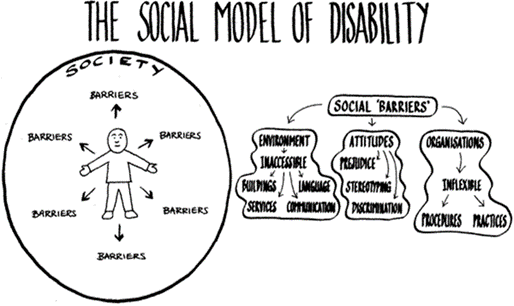

Figure: Social Model of Disability (IASC 2019)

The frequently cited landmark in the development of disability theory was the publication of the Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS) document Fundamental Principles of Disability in 1976:

‘In our view, it is society which disables physically impaired people. Disability is something imposed on top of our impairments, by the way we are unnecessarily isolated and excluded from full participation in society. Disabled people are therefore an oppressed group in society.’ (UPIAS 1976: 3)

Impairment is the condition … lacking a part or all of a limb, having a defective limb, organ or part of the body

Disability is identified as separate from impairment, with disability being defined as ‘the disadvantage or restriction of activity caused by contemporary social organisation which takes no or little account of people who have impairments and thus excludes them from the mainstream of social activities.’

There have been challenges and extensions to the medical and social models of disability, and the field is constantly expanding to respond to modern conditions and circumstances.

Post-Structuralist Models of Disability

A number of scholars have noted that the Social Model appeared to become a ‘sacred cow’ in that any debate about its veracity was seen by activists to reflect discriminatory attitudes and to support medicalised, essentialist notions of disability. Post-modernists argued that the Social Model ignored actual impairment, and therefore failed to acknowledge issues of embodiment.

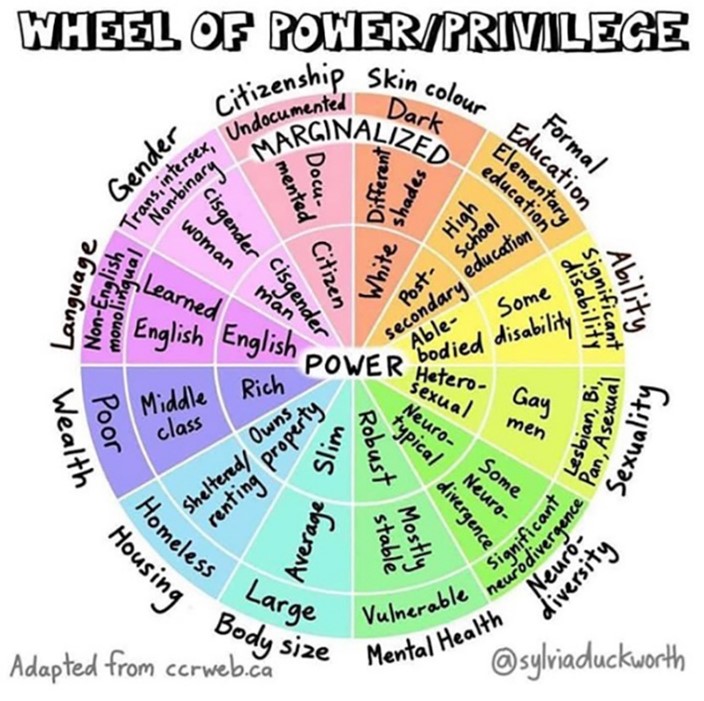

Some such as Shakespeare argued that the binary opposition of impairment (as physical) and disability (as social) fails to address the social nature of physical impairments, or the practical reality that a disability is caused by impairment (Shakespeare 2006: 34). Post-structuralist accounts incorporate more complex theories of the subject, and claim that ‘the meta-narrative of disabled people does not recognise diversity within the category of disability, and the significance of the intersection of disability with other axes of inequality, such as gender or race : the issue of intersectionality, power and privilege (Shakespeare and Corker 2002:15).

Figure: The Wheel of Power and Privilege ((Duckworth 2019)

The Social Relational Model

In Thomas’s (1999) synthesised account of disability, it is the interaction between impairment and disability in a social setting which creates oppression.

Disability is a form of social oppression involving the social imposition of restrictions of activity on people with impairments and the socially engendered undermining of their psycho-emotional wellbeing (Thomas, 1999: 7). Disability only comes into play when the restrictions of activity experienced by people with impairments are socially imposed. Thomas conceptualised impairment as having both a physical dysfunction dimension and a socially constructed dimension. She conceived disability to be the restrictions to daily living caused by both the impairment and the social arrangements which result in the oppression of disabled people, and drew on feminist theorists to extend the definition to include the psycho-emotional dimensions of disability.

Post-Humanism and Disability Studies

Posthuman disability theory critiques traditional humanism, which defines “human” through ableist ideals of perfection, arguing that disability exposes the outdated nature of the concept of the human (Goodley 2024)

It examines how emerging technologies and changing relationships with non-human elements (like biotechnology, genetics, AI and animals) challenge and expand understandings of the body, identity, and agency.

Critique of Humanism:

Posthuman disability theory directly challenges humanist ideals that centre on a white, male, and non-disabled subject, viewing this definition of the “human” as inherently flawed and outdated.

Further Developments of the Theoretical Models

For an excellent summary of the development of Disability Theory beyond the above models, including consideration of global models which acknowledge variation in ideas beyond a Westernised perspective, read Dan Goodley’s introductory chapter from his book, Disability Studies: An Interdisciplinary Introduction (2017, pages 1-21). This encompasses four over-arching models of disability: social, minority, cultural and relational, which begin the process of decolonising the discipline, and paying attention to under-represented approaches.

Section 2: Research Findings on Disability and Higher Education

Morina (2017: 5) completed a detailed systematic literature review of the issues for disabled students, and summarised the lived experience detailed in the research: ‘These students’ paths are frequently very difficult, somewhat like an obstacle course, and students even define themselves as survivors and long-distance runners’. The author highlighted the key findings across many studies:

- negative attitudes displayed by teaching staff

- architectural barriers;

- inaccessible information and technology;

- rules and policies that are not actually enforced

- teaching methodologies that do not favour inclusion

In addition, she highlighted the low disclosure rate for ‘hidden disabilities’. She found that students’ perceptions about hidden disabilities are closely related to the concept of ‘normality’, and they may choose non-disclosure if they desire to be considered and treated as ‘normal’. They may also choose not to share their disability if they feel that disclosure would place them at a disadvantage or they the fear being stigmatised or labelled, or simply because they think they have no special needs or disability. She also found that universities are still largely driven to provide individual reasonable adjustments, particularly in relation to learner support services, rather than universal, inclusive provision (Collins et al. 2019: 1485).

BUT most significantly, outcomes in most categories were found to be similar to non-disabled peers: it is the lived experience, and the journey through the university, through teaching practices, attitudes, resits, interruptions of study, or the challenges of extenuating circumstances, which creates the disadvantage and exclusion of disabled students.

There were three key topics across a number of studies: attitudes of the faculty members towards disabled students; faculty training in disability and inclusive education; and universal design for learning strategies (Morina 2016; Collins et al, 2019).

- Attitudes: Research shows that in the main academic staff showed a positive attitude towards disabilities but although they valued the strategies of inclusive education in theory, they did not implement them in practice. Interestingly, these results do not coincide with the opinions of the disabled students, who identified the attitudes of the faculty members towards them as the most significant barrier.

- Training: there was a need identified for faculty for training and sensitisation towards disabilities. Attitudes of faculty members improved after they had been trained and had more experience in how to respond to the needs of the disabled students.

- Universal Design for Learning: Students benefit from academic staff who apply the principles of the universal design for learning. If the faculty members used universal design, adaptations would not be necessary. Universal design for learning benefits all students, with or without disabilities (Edwards et al 2022)

Disability and Assessment: Nieminen et al. (2024): Literature Review

In the study, 40 of the 42 studies examined reported experiences of exclusion.

The researchers noted two intertwined yet partly separate missions of preventing exclusion and promoting inclusion in assessment. Findings regarding exclusion were alarming. For example, 12 of the 42 studies reported outright experiences of discrimination. The first step towards more inclusive assessment is thus to prevent such exclusionary assessment situations.

Assessment is an important technology for regulating the inclusion/exclusion of students with disabilities in HE. This clashes with the conceptualisation of assessment as an objective, ‘neutral’ process of measuring cognitive learning outcomes, and highlights the socially constructed and ableist nature of assessment.

Nieminen, J. H., Anabel Moriña, and Gilda Biagiotti. 2024c. “Assessment as a Matter of Inclusion: A Meta-Ethnographic Review of the Assessment Experiences of Students with Disabilities in Higher Education.” Educational Research Review 42: 100582. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2023.100582.

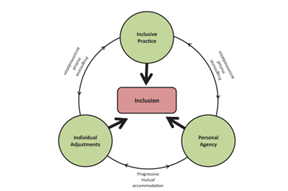

The Role of Personal Agency

Recent research has explored the role of personal agency, self-regulation, self-advocacy and self-care, and has suggested the need for progressive accommodations to support disabled students’ development: ‘A significant challenge for HEIs is how to find an appropriate balance between creating ‘inclusive’ learning environments which accommodate all students, recognise where it is necessary to make specific adjustments for individuals with particular needs, and work in partnership with the learner.’ (Hewitt et al. 2018: 766).

In this approach we recognise students may initially require individualised support and reasonable adjustments, but work with them to develop independence, self-advocacy and agency, reducing accommodations and enabling their progress towards independence and employability.

Figure: Balancing inclusive design, individual adjustments and individual agency for students with disabilities in higher education (Hewitt et al. 2020).

Recording of Disability and Reasonable Adjustments Section

Digital Accessibility

Getting Started with Digital Accessibility

Ensuring accessibility in our teaching and learning is essential for supporting the needs of our diverse community. By making our resources and online environments accessible, we help all students and staff achieve their full potential.

Why digital accessibility is important

Digital accessibility ensures that everyone has equal access to information and opportunities. In the UK, approximately one in five people have a disability, including around eight million working-age individuals (Office for National Statistics Census 2021). This includes many of our students and staff. By creating accessible digital environments, we ensure that everyone can fully engage in academic and professional activities.

The social model of disability

The social model of disability proposes that it is not the individual’s impairment that is disabling, but rather societal barriers and attitudes (Oliver 1990, Scope 2024). This perspective shifts the focus from what individuals cannot do to what society can do to remove barriers. By making our digital content accessible, we actively remove obstacles and create an inclusive environment.

Legal obligations and accessible design

Accessibility standards are best practices that improve the experiences of everyone in all areas of learning and work. The University is legally required to meet accessibility standards on its websites, intranets, and mobile apps. The Equality Act (2010) places a legal responsibility on us all to not only make reasonable adjustments for individuals but also proactively design our digital environments to be accessible. Recent regulations, The Public Sector Bodies Accessibility Requirements (2020), reinforce this legal obligation by requiring public sector organisations, including universities, to ensure all digital materials are accessible. Cardiff University is committed to this goal, making digital accessibility a key objective in the Strategic Equality Plan.

Digital accessibility principles

Digital accessibility means that people can access information, learn, and do what they need to do in a similar amount of time and effort as others, whether they have a disability or not. To achieve this, content and activities need to be:

- Accessible: Information must be easily accessible in various formats for different senses (hearing, sight, etc.). For instance, use alternative text (Alt text) for images, captions for videos, and transcripts for audio content.

- Understandable: Information should make sense to anyone accessing it. This includes using clear and simple language, providing instructions, and ensuring predictable navigation.

- Usable: Users should be able to easily navigate, interact with, and move through the content. It should be compatible with assistive technologies, such as screen readers, and provide enough time for users to engage with and understand the material.

Steps to enhancing digital accessibility:

1. Choose appropriate tools:

Create and deliver your materials and activities using tools that support accessible content. Tools used by the university (e.g., Microsoft Office tools, Panopto) typically meet accessibility requirements. Ensure any external materials you use also meet accessibility standards.

2. Create Accessible Learning Materials

a. General Guidelines:

• Use technology thoughtfully to minimise barriers and enhance accessibility.

• Provide materials electronically, in advance where possible, to allow learners to adjust settings to their needs, such as font size or colour contrast.

b. Word Documents:

• Save documents in accessible formats like Rich Text Format (.rtf) or HTML.

• Use a table of contents for long documents for easy navigation.

• Avoid floating text boxes; they can disrupt the reading sequence for screen readers.

c. PDFs:

• Use Optical Character Recognition (OCR) for scanned documents to make text readable.

• Ensure tables are described in text or include alternative text (‘Alt text’).

• Create tagged PDFs for better accessibility using tools like Adobe Acrobat or Microsoft Office.

d. Presentations:

• Provide detailed notes in the ‘Notes’ field to supplement bullet points.

• Describe images with ‘alt text’ tags or notes.

• Use animations purposefully and ensure they are not distracting.

• Consider exporting presentations to Word or HTML for better accessibility.

e. Web Pages:

• Use software that produces accessible, standards-based HTML.

• Verify accessibility using online tools like WAVE.

f. Multimedia:

• Provide content in multiple formats (text, audio, video) to cater to different needs.

• Ensure audio and video include transcripts and captions.

3. Improve visibility, readability and audibility

• Colours: Ensure good contrast between text and background, but avoid extreme contrast (e.g., opt for dark grey text on an off-white background). Avoid using colour as the only means to convey information.

For further information see: Designing PowerPoint slides for people with dyslexia

• Text: Use a simple sans-serif font (the default font is often best). Avoid formatting like capitalizing, underlining, or italicizing- especially for large portions of text. Use bold for emphasis only. Left-justify your text.

For further information see: Styles in Microsoft Word

• Audio: Speak slowly and clearly and try to eliminate background noise. Provide transcripts and captions for audio content.

4. Provide options and alternatives

• Alternative text: Add descriptive alternative text (‘Alt text’) to images to describe their appearance and function. Alt text is crucial for users with visual impairments as screen reader software relies on this text to describe image content. For further information see: Adding Alt text in Word and Powerpoint and Microsoft guide to writing good Alt text

• Multiple formats: Offer documents in various formats, such as Word and PDF - note that PDFs are often inaccessible. Use tools like SensusAccess and Blackboard Ally File Transformer to convert documents into accessible formats.

• Transcriptions and captions: Include descriptive transcriptions for audio content and add captions to videos. Many university tools, such as Panopto, include these functions.

5. Use clear meaningful language

• Descriptive links: For links, instead of “Click here” use clear, descriptive text that clearly indicates the link's destination or purpose.

• Plain English: Write in plain English and avoid complex language or figurative speech, homonyms and homophones where possible.

• Clear instructions: When sharing resources provide clear instructions on how to use them, both before and during the session. Offer detailed descriptions of resources, options, and alternatives, offering as much flexibility as possible to help users prepare and engage effectively.

6. Structure your materials clearly and consistently

• Headings: Use built-in heading styles to define document structure, aiding navigation and accessibility. This allows assistive technology to make sense of your materials, which is especially important for users with visual impairments or motor difficulties.

• Tables: Keep tables simple; avoid split or merged cells whenever possible.

• Layout: Use a consistent layout, clearly distinguishing between activities, text blocks, and essential versus optional information or activities.

7. Checking accessibility of your work

Accessibility Checkers: Use tools to scan and improve your content’s accessibility.

Microsoft Accessibility Checker: A built-in tool in Microsoft Office that helps identify and fix accessibility issues in documents.

Blackboard Ally: A built-in tool which provides feedback on the accessibility of your course materials and offers practical advice on how to improve them.

WAVE Accessibility Tool: A free tool that evaluates web pages for accessibility issues.

By incorporating digital accessibility into the design of teaching and learning materials we can create inclusive learning environments. By anticipating diverse needs and using the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) Framework UDL framework as a guide to offer multiple means of representation, action and expression, and engagement, we can remove barriers to learning and promote equity. Embracing accessibility not only fulfils legal obligations but also enriches the educational experience for everyone. It is essential for us all to proactively design our content and activities to be accessible, fostering a supportive and inclusive community for our diverse learners and staff.

To find out more about Digital Accessibility, access this Xerte learning resource offers some simple steps you can take to make your digital content more accessible:

Recording of Digital Accessibility section

Where Next?

The Inclusive Education CPD Offer

Toolkit

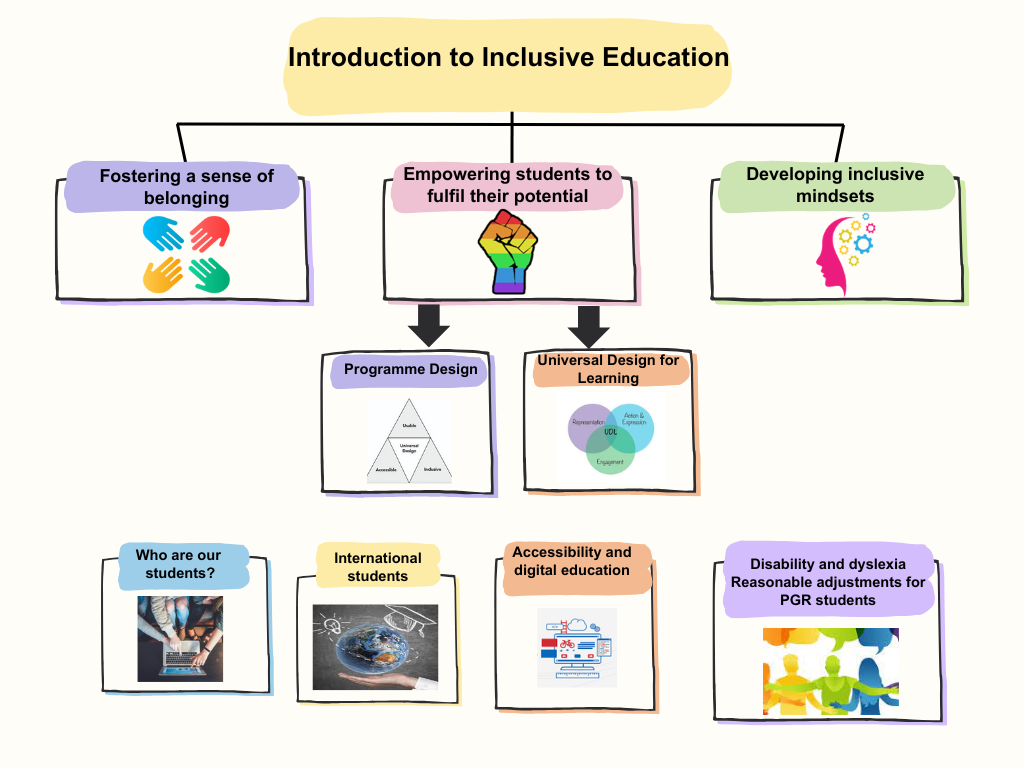

You can now develop your understanding of Inclusive Education by accessing the related pages on specific topics, outlined in the map below, which relate to the Inclusive Education Framework. After accessing this page, we recommend you review all toolkit pages in the inclusive education series and consider more professional development.

Workshops

You can develop your understanding of Inclusive Education by attending workshop sessions that relate to each topic. These workshops can be taken in a live face-to-face session, if you prefer social interactive learning, or can be completed asynchronously in your own time, if preferred. You can find out more information on workshops, and the link to book here.

Bespoke School Provision

We offer support for Schools on Inclusive Education, through the Education Development service. This can be useful to address specific local concerns, to upskill whole teams, or to support the programme approval and revalidation process. Please contact your School’s Education Development Team contact for more information.

Map of Topics

Below is a map of the toolkit and workshop topics, to aid your navigation. These will be developed and added to in future iterations of this toolkit:

You’re on page 8 of 9 Inclusivity theme pages. Explore the others here:

1.Inclusivity and the CU Inclusive Education Framework

2.Introduction to Inclusive education

3.Fostering a sense of belonging

4.Empowering students to fulfil their potential

5.Developing Inclusive Mindsets

6.Universal Design for Learning

8.Disability and Reasonable Adjustments

Or how about another theme?

Disability and Dyslexia page References

References

AHEAD. 2023. UDL and the Continuum of Support. Available at: https://www.ahead.ie/udl-pyramid

BDA 2023. Dyslexia Fact Sheet. Available at: https://cdn.bdadyslexia.org.uk/uploads/documents/British-Dyslexia-Association-Dyslexia-Factsheet.pdf?v=1702999710

Bunbury, M. 2020. Disability in higher education – do reasonable adjustments contribute to an inclusive curriculum?, International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24:9, 964-979,

CAST. 2021. Universal Design for Learning Guidelines. Available at: https://www.cast.org/impact/universal-design-for-learning-udl

CAST 2018. UDL and Assessment. http://udloncampus.cast.org/page/assessment_udl

Collins, A. Azmat, F. and Rentschler, R. 2019. ‘Bringing everyone on the same journey’: revisiting inclusion in higher education, Studies in Higher Education, 44:8, 1475-1487, DOI: 10.1080/03075079.2018.1450852

Disabled Students UK. 2023. The Access Insights 2023 Report. Available at: https://disabledstudents.co.uk/research/

Duckworth, S. 2019. Wheel of Power, Privilege, and Marginalization, by Sylvia Duckworth. Used by permission. To our knowledge, the original version comes from the Canadian Council of Refugees (CCR): https://ccrweb.ca/en/anti-oppression.

Dobson Waters, S. and Torgerson, C. J.. 2020. Dyslexia in higher education: a systematic review of interventions used to promote learning, Journal of Further and Higher Education, 45(2), 226–256. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877x.2020.1744545

Edwards, M. Poed, S. Al-Nawab, H. Penna, O. 2022. Academic accommodations for university students living with disability and the potential of universal design to address their needs Higher Education (2022) 84: 779–799

EHRC 2014. What equality law means for you as an education provider – further and higher education. https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/what_equality_law_means_for_you_as_an_education_provide_further_and_higher_education.pdf

Goodley, D. 2017. Disability Studies: An interdisciplinary introduction. London: Sage

Hamilton, L. and Petty, s. 2023. Compassionate pedagogy for neurodiversity in higher education: A conceptual analysis. Frontiers in Psychology Vol 14 Feb 2023. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1093290/full

Hewett, R. Douglas, G. McLinden, M. and Keil, S. 2020. Balancing inclusive design, adjustments and personal agency: progressive mutual accommodations and the experiences of university students with vision impairment in the United Kingdom. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24:7, 754-770, DOI: 10.1080/13603116.2018.1492637

Hockings, C. 2010. Inclusive Learning and Teaching in Higher Education: A Synthesis of Research. York: Higher Education Academy.

Lawrie, G., Marquis, E., Fuller, E., Newman, T., Qui, M., Nomikoudis, M., Roelofs, F., & van Dam, L. (2017) Moving towards inclusive learning and teaching: A synthesis of recent literature. Teaching and Learning Inquiry 5 (1)

Morina, A. 2017 Inclusive education in higher education: challenges and opportunities, European Journal of Special Needs Education, 32:1, 3-17, DOI: 10.1080/08856257.2016.1254964

Pavey, B., Meehan, M. & Waugh, A. (2010 Dyslexia-friendly Further & Higher Education. London: Sage.

Ryder, S. and Norwich, B. 2018. UK higher education lecturers’ perspectives of dyslexia, dyslexic students and related disability provision. JORSEN 19: 161-172 https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12438

Shakespeare, T. 2006. Disability Rights and Wrongs. London: Routledge

Shakespeare, T. and Corker, M. 2002. Disability/Postmodernity: Embodying Disability Theory. Continuum Press

Signhealth. 2023. Learn about Deafness. Available at : https://signhealth.org.uk/resources/learn-about-deafness/

Snowling, M. J. (2008). Specific Disorders and Broader Phenotypes: The Case of Dyslexia. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 61(1), 142-156

Tai, J. et al. 2022. Assessment for inclusion: rethinking contemporary strategies in assessment design. Higher Education Research and Development (Online) DOI: 10.1080/07294360.2022.2057451

Thomas, C. 1999. Female Forms: Experiencing and Understanding Disability. London: OUP

Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS). 1976. Fundamental Principles of Disability. London: UPIAS

UCAS 2022. NEXT STEPS: WHAT IS THE EXPERIENCE OF DISABLED STUDENTS IN EDUCATION? Available at: https://www.ucas.com/next-steps-what-experience-disabled-students-education?hash=Khe12QF8sBath7P7hVMMpU9lSoJrAtS5f9zaLjf2-MI

Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS). 1976. Fundamental Principles of Disability. London: UPIAS