Introduction

Introduction

Firstly, some perspectives on disability in university :

1. Conceptualising Disability

Figure: The nine protected characteristics in the Equality Act 2010

The UK Equality Act (2010) defines the nine protected characteristics illustrated in the figure above, and also defines disability:

You are disabled if you have: a physical or mental impairment that has a ‘substantial’ and ‘long-term’ negative effect on your ability to do normal daily activities. ‘Substantial’ is more than minor or trivial; ‘long-term’ means 12 months or more.

The Equality Act 2010 applies to all sectors of education, including Higher Education, and defines our responsibilities to provide accessible, anticipatory education for all (see the Supporting Disabled Students section, below).

Models of Disability

How we conceive of disability will impact how we design and deliver our teaching, and how we respond to disabled students in Cardiff University. There is a vast literature on Disability Studies, which has developed as a discipline alongside new ideas about the nature of disability since the 1970s. The two key concepts are explored below, with further detail and models in the Deeper Dive Section, at the end of the page, should you wish to deepen your understanding. You can also read a summary of the developments in Dan Goodley’s Disability Studies book (2017), in the reference list.

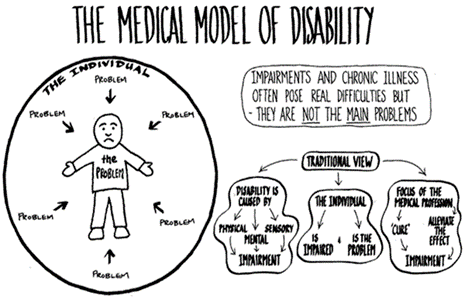

The Medical Model of disability is prevalent in the UK, and conceives of disability as intrinsic to the individual, caused by physical, sensory or medical impairment, and a ‘condition’ in need of treatment. This leads to medically-dominated provision of services, based around diagnoses, with an aim to ‘normalise’ individuals through therapeutic intervention.

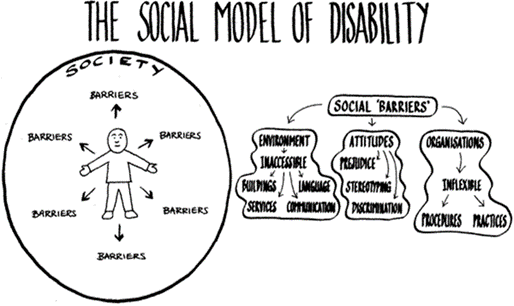

The Social Model of Disability challenges these medicalised assumptions, and suggests that while impairment is the condition, such as lacking a part or all of a limb, having a defective limb, organ or part of the body, disability is identified separately, being defined as ‘the disadvantage or restriction of activity caused by contemporary social organisation which takes no or little account of people who have impairments and thus excludes them from the mainstream of social activities.’

Disability and Higher Education

If we apply the social model to higher education, we can appreciate that disability is created by the traditional processes, procedures and practices of learning, teaching and assessment. It is also created by our organisational processes and methods of communication.

These processes, procedures and practices create barriers to learning and attainment for our disabled students. For example a requirement for a diagnosis or assessment prior to an adjustment to teaching practice or assessment would be an illustration of the medical model, whereas flexible, inclusive or universally-designed learning would be an example of the social model.

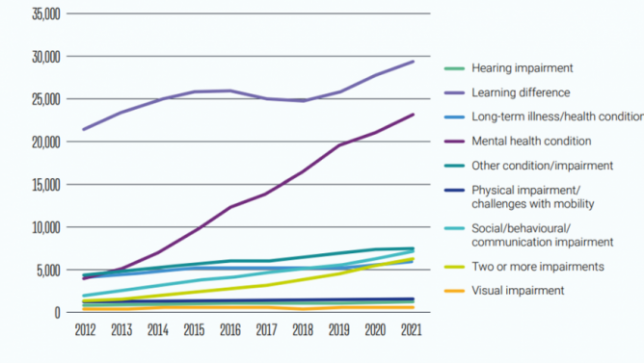

UCAS (2022) completed a detailed study of disabled students in higher education, tracking the changes to the population since 2012. They found:

- Issues in under-representation: one in five working-age adults in the UK are disabled, compared to one in seven HE students

- The most prevalent category: more than a third (35%) of disabled applicants shared a learning difference (e.g. dyslexia or dyscalculia) – the most commonly shared category, representing 5% of all UK applicants

- Significant changes in the needs of students: Since 2012, the greatest increases in people feeling able to share their needs have been seen for mental health conditions (+453%) and social, behavioural or communication impairments (+249%).

Figure: Numbers of disabled students by category 2012-2021 (UCAS 2022)

Similarly, in Cardiff University, the number of disabled students has risen over the last 5 years. Cardiff University Staff can find data on Disability and Reasonable adjustments here.

Thus an effective, supportive approach to our students who are disabled is crucial, to ensure we remove barriers to learning and ensure all students can achieve their potential.

There is extensive further research on the gaps, experiences and outcomes for disabled students: to explore more, read the Research Findings on Disability and Higher Education section, in the Deeper Dive, below..

Deeper Dive

Section 1: Models of Disability

Figure: Medical Model of Disability (IASC 2019)

As summarised in the introduction to this page, the medical model of disability is prevalent in the UK, and conceives of disability as:

- Intrinsic to the individual

- Caused by physical, sensory or medical impairment

- A ‘condition’ in need of treatment

This leads to medically-dominated provision of services, based around diagnoses, with an aim to ‘normalise’ individuals through therapeutic intervention.

Charity, Tragedy or Moral Model

A related understanding is the tragedy model, often used in adverts and fund-raising, where the tragic ‘victim’ is seen as deserving pity and help, or if the person is portrayed as ‘over-coming suffering’, they become the inspiring role-model.

The Social Model of Disability

Figure: Social Model of Disability (IASC 2019)

The frequently cited landmark in the development of disability theory was the publication of the Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS) document Fundamental Principles of Disability in 1976:

‘In our view, it is society which disables physically impaired people. Disability is something imposed on top of our impairments, by the way we are unnecessarily isolated and excluded from full participation in society. Disabled people are therefore an oppressed group in society.’ (UPIAS 1976: 3)

Impairment is the condition … lacking a part or all of a limb, having a defective limb, organ or part of the body

Disability is identified as separate from impairment, with disability being defined as ‘the disadvantage or restriction of activity caused by contemporary social organisation which takes no or little account of people who have impairments and thus excludes them from the mainstream of social activities.’

There have been challenges and extensions to the medical and social models of disability, and the field is constantly expanding to respond to modern conditions and circumstances.

Post-Structuralist Models of Disability

A number of scholars have noted that the Social Model appeared to become a ‘sacred cow’ in that any debate about its veracity was seen by activists to reflect discriminatory attitudes and to support medicalised, essentialist notions of disability. Post-modernists argued that the Social Model ignored actual impairment, and therefore failed to acknowledge issues of embodiment.

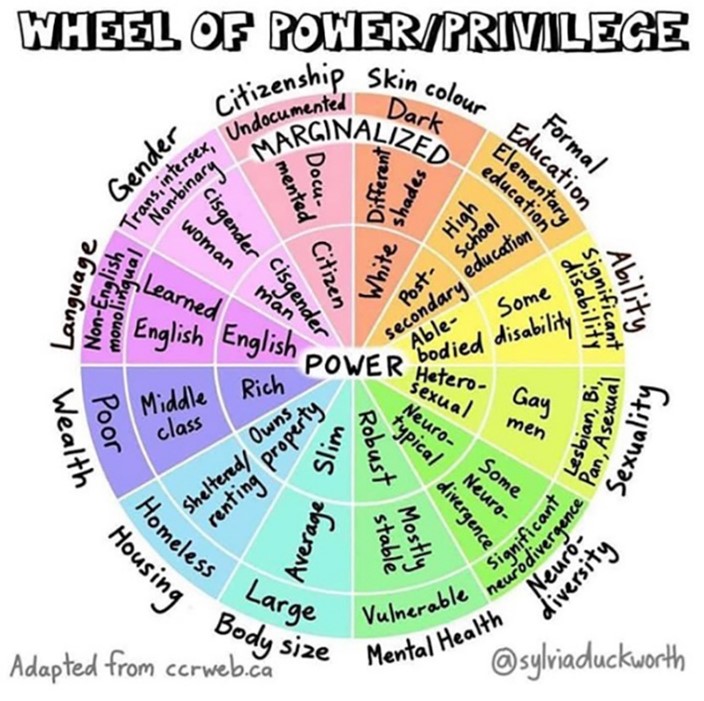

Some such as Shakespeare argued that the binary opposition of impairment (as physical) and disability (as social) fails to address the social nature of physical impairments, or the practical reality that a disability is caused by impairment (Shakespeare 2006: 34). Post-structuralist accounts incorporate more complex theories of the subject, and claim that ‘the meta-narrative of disabled people does not recognise diversity within the category of disability, and the significance of the intersection of disability with other axes of inequality, such as gender or race : the issue of intersectionality, power and privilege (Shakespeare and Corker 2002:15).

Figure: The Wheel of Power and Privilege ((Duckworth 2019)

The Social Relational Model

In Thomas’s (1999) synthesised account of disability, it is the interaction between impairment and disability in a social setting which creates oppression.

Disability is a form of social oppression involving the social imposition of restrictions of activity on people with impairments and the socially engendered undermining of their psycho-emotional wellbeing (Thomas, 1999: 7). Disability only comes into play when the restrictions of activity experienced by people with impairments are socially imposed. Thomas conceptualised impairment as having both a physical dysfunction dimension and a socially constructed dimension. She conceived disability to be the restrictions to daily living caused by both the impairment and the social arrangements which result in the oppression of disabled people, and drew on feminist theorists to extend the definition to include the psycho-emotional dimensions of disability.

Further Developments of the Theoretical Models

For an excellent summary of the development of Disability Theory beyond the above models, including consideration of global models which acknowledge variation in ideas beyond a Westernised perspective, read Dan Goodley’s introductory chapter from his book, Disability Studies: An Interdisciplinary Introduction (2017, pages 1-21). This encompasses four over-arching models of disability: social, minority, cultural and relational, which begin the process of decolonising the discipline, and paying attention to under-represented approaches.

Section 2: Research Findings on Disability and Higher Education

Morina (2017: 5) completed a detailed systematic literature review of the issues for disabled students, and summarised the lived experience detailed in the research: ‘These students’ paths are frequently very difficult, somewhat like an obstacle course, and students even define themselves as survivors and long-distance runners’. The author highlighted the key findings across many studies:

- negative attitudes displayed by teaching staff

- architectural barriers;

- inaccessible information and technology;

- rules and policies that are not actually enforced

- teaching methodologies that do not favour inclusion

In addition, she highlighted the low disclosure rate for ‘hidden disabilities’. She found that students’ perceptions about hidden disabilities are closely related to the concept of ‘normality’, and they may choose non-disclosure if they desire to be considered and treated as ‘normal’. They may also choose not to share their disability if they feel that disclosure would place them at a disadvantage or they the fear being stigmatised or labelled, or simply because they think they have no special needs or disability. She also found that universities are still largely driven to provide individual reasonable adjustments, particularly in relation to learner support services, rather than universal, inclusive provision (Collins et al. 2019: 1485).

BUT most significantly, outcomes in most categories were found to be similar to non-disabled peers: it is the lived experience, and the journey through the university, through teaching practices, attitudes, resits, interruptions of study, or the challenges of extenuating circumstances, which creates the disadvantage and exclusion of disabled students.

There were three key topics across a number of studies: attitudes of the faculty members towards disabled students; faculty training in disability and inclusive education; and universal design for learning strategies (Morina 2016; Collins et al, 2019).

- Attitudes: Research shows that in the main academic staff showed a positive attitude towards disabilities but although they valued the strategies of inclusive education in theory, they did not implement them in practice. Interestingly, these results do not coincide with the opinions of the disabled students, who identified the attitudes of the faculty members towards them as the most significant barrier.

- Training: there was a need identified for faculty for training and sensitisation towards disabilities. Attitudes of faculty members improved after they had been trained and had more experience in how to respond to the needs of the disabled students.

- Universal Design for Learning: Students benefit from academic staff who apply the principles of the universal design for learning. If the faculty members used universal design, adaptations would not be necessary. Universal design for learning benefits all students, with or without disabilities (Edwards et al 2022)

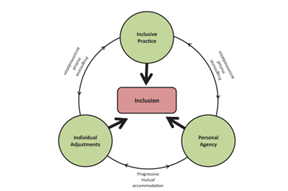

The Role of Personal Agency

Recent research has explored the role of personal agency, self-regulation, self-advocacy and self-care, and has suggested the need for progressive accommodations to support disabled students’ development: ‘A significant challenge for HEIs is how to find an appropriate balance between creating ‘inclusive’ learning environments which accommodate all students, recognise where it is necessary to make specific adjustments for individuals with particular needs, and work in partnership with the learner.’ (Hewitt et al. 2018: 766).

In this approach we recognise students may initially require individualised support and reasonable adjustments, but work with them to develop independence, self-advocacy and agency, reducing accommodations and enabling their progress towards independence and employability.

Figure: Balancing inclusive design, individual adjustments and individual agency for students with disabilities in higher education (Hewitt et al. 2020).

Disability and Dyslexia page References

References

AHEAD. 2023. UDL and the Continuum of Support. Available at: https://www.ahead.ie/udl-pyramid

BDA 2023. Dyslexia Fact Sheet. Available at: https://cdn.bdadyslexia.org.uk/uploads/documents/British-Dyslexia-Association-Dyslexia-Factsheet.pdf?v=1702999710

Bunbury, M. 2020. Disability in higher education – do reasonable adjustments contribute to an inclusive curriculum?, International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24:9, 964-979,

CAST. 2021. Universal Design for Learning Guidelines. Available at: https://www.cast.org/impact/universal-design-for-learning-udl

CAST 2018. UDL and Assessment. http://udloncampus.cast.org/page/assessment_udl

Collins, A. Azmat, F. and Rentschler, R. 2019. ‘Bringing everyone on the same journey’: revisiting inclusion in higher education, Studies in Higher Education, 44:8, 1475-1487, DOI: 10.1080/03075079.2018.1450852

Disabled Students UK. 2023. The Access Insights 2023 Report. Available at: https://disabledstudents.co.uk/research/

Duckworth, S. 2019. Wheel of Power, Privilege, and Marginalization, by Sylvia Duckworth. Used by permission. To our knowledge, the original version comes from the Canadian Council of Refugees (CCR): https://ccrweb.ca/en/anti-oppression.

Dobson Waters, S. and Torgerson, C. J.. 2020. Dyslexia in higher education: a systematic review of interventions used to promote learning, Journal of Further and Higher Education, 45(2), 226–256. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877x.2020.1744545

Edwards, M. Poed, S. Al-Nawab, H. Penna, O. 2022. Academic accommodations for university students living with disability and the potential of universal design to address their needs Higher Education (2022) 84: 779–799

EHRC 2014. What equality law means for you as an education provider – further and higher education. https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/what_equality_law_means_for_you_as_an_education_provide_further_and_higher_education.pdf

Goodley, D. 2017. Disability Studies: An interdisciplinary introduction. London: Sage

Hamilton, L. and Petty, s. 2023. Compassionate pedagogy for neurodiversity in higher education: A conceptual analysis. Frontiers in Psychology Vol 14 Feb 2023. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1093290/full

Hewett, R. Douglas, G. McLinden, M. and Keil, S. 2020. Balancing inclusive design, adjustments and personal agency: progressive mutual accommodations and the experiences of university students with vision impairment in the United Kingdom. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24:7, 754-770, DOI: 10.1080/13603116.2018.1492637

Hockings, C. 2010. Inclusive Learning and Teaching in Higher Education: A Synthesis of Research. York: Higher Education Academy.

Lawrie, G., Marquis, E., Fuller, E., Newman, T., Qui, M., Nomikoudis, M., Roelofs, F., & van Dam, L. (2017) Moving towards inclusive learning and teaching: A synthesis of recent literature. Teaching and Learning Inquiry 5 (1)

Morina, A. 2017 Inclusive education in higher education: challenges and opportunities, European Journal of Special Needs Education, 32:1, 3-17, DOI: 10.1080/08856257.2016.1254964

Pavey, B., Meehan, M. & Waugh, A. (2010 Dyslexia-friendly Further & Higher Education. London: Sage.

Ryder, S. and Norwich, B. 2018. UK higher education lecturers’ perspectives of dyslexia, dyslexic students and related disability provision. JORSEN 19: 161-172 https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12438

Shakespeare, T. 2006. Disability Rights and Wrongs. London: Routledge

Shakespeare, T. and Corker, M. 2002. Disability/Postmodernity: Embodying Disability Theory. Continuum Press

Signhealth. 2023. Learn about Deafness. Available at : https://signhealth.org.uk/resources/learn-about-deafness/

Snowling, M. J. (2008). Specific Disorders and Broader Phenotypes: The Case of Dyslexia. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 61(1), 142-156

Tai, J. et al. 2022. Assessment for inclusion: rethinking contemporary strategies in assessment design. Higher Education Research and Development (Online) DOI: 10.1080/07294360.2022.2057451

Thomas, C. 1999. Female Forms: Experiencing and Understanding Disability. London: OUP

Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS). 1976. Fundamental Principles of Disability. London: UPIAS

UCAS 2022. NEXT STEPS: WHAT IS THE EXPERIENCE OF DISABLED STUDENTS IN EDUCATION? Available at: https://www.ucas.com/next-steps-what-experience-disabled-students-education?hash=Khe12QF8sBath7P7hVMMpU9lSoJrAtS5f9zaLjf2-MI

Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS). 1976. Fundamental Principles of Disability. London: UPIAS

Where Next?

Map of Topics

Below is a map of the toolkit and workshop topics, to aid your navigation. These will be developed and added to in future iterations of this toolkit:

You’re on page 8 of 9 Inclusivity theme pages. Explore the others here:

Inclusivity and the CU Inclusive Education Framework

Introduction to Inclusive education

Fostering a sense of belonging

Empowering students to fulfil their potential