Empowering Students to Fulfil their Potential

Getting Started

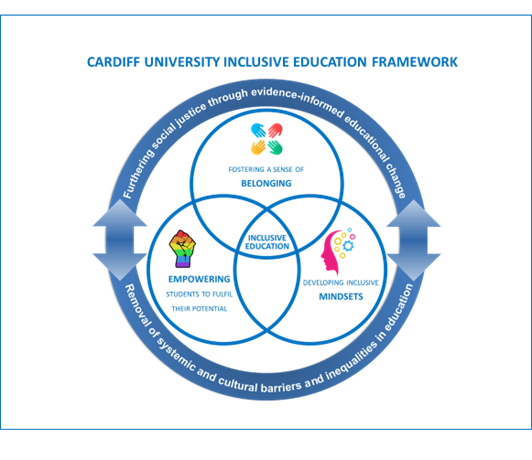

The Cardiff University Inclusive Education Framework

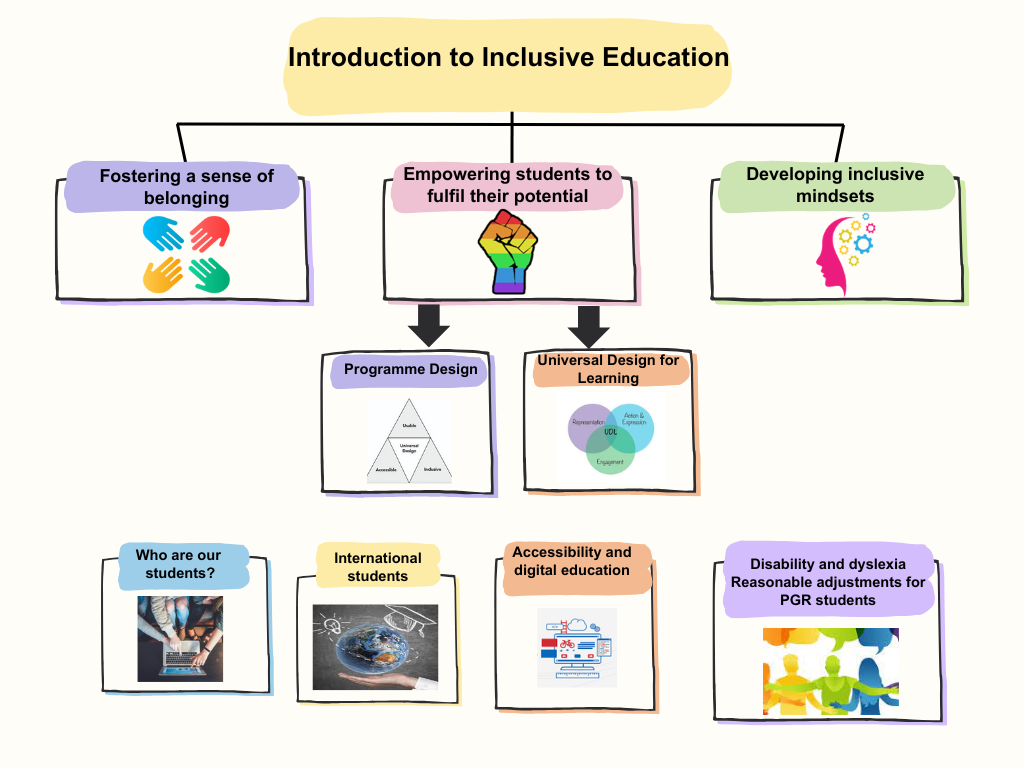

We have developed a university-wide framework for facilitating and supporting schools and departments to embed inclusive education within our educational provision. Inclusive Education links to both the wellbeing of our students, and student satisfaction and experience, and it sits with the ‘creating an inclusive learning community’ priority. You can read more on the Framework on the Introduction to Inclusive Education page.

Empowering Students to Fulfil their Potential

‘Empowering students to fulfil their potential’ is one of the three dimensions of the framework, as The Future Generations Act 2015 aims for ‘a society that enables people to fulfil their potential no matter what their background or circumstances’. Inclusive education at Cardiff University will support all students to achieve their potential through three key areas of focus relating to the principles and practices of inclusive learning and teaching:

- Providing learning that is authentic, meaningful and relevant by recognising the needs and perspectives of all learners, and designing for all

- Supporting all students to fully participate in learning activities

- Enabling all students to demonstrate their abilities, skills and knowledge

The following applies to all learning and teaching: alternatively, you can jump straight to Inclusive Programme Design, at the bottom of the page.

Key Considerations

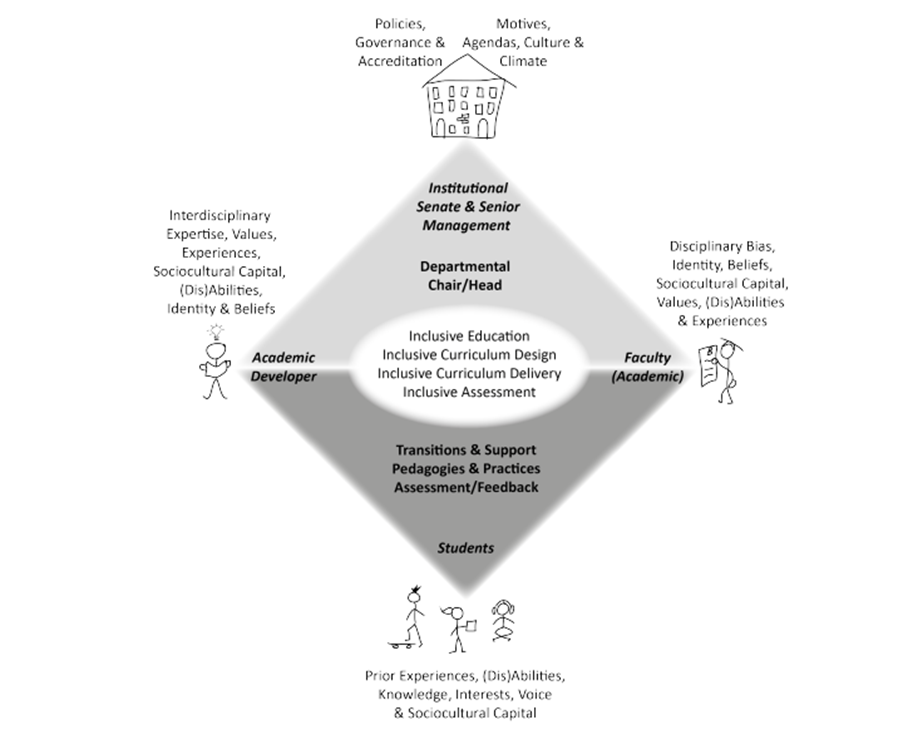

Educators work within institutional frameworks, policies, agendas, cultures and climates. Hockings (2010) outlines four broad areas of focus for inclusive education in higher education: inclusive curriculum design, inclusive curriculum delivery, inclusive assessment, and institutional commitment to, and management of, inclusive learning and teaching.

Figure 2: A schematic representation of the shared understanding and relationships required between stakeholders (Lawrie et al. 2017)

Lawrie et al. (2017) develop this further, suggesting that the broader institutional contexts in which education unfolds represent a critical issue for inclusion. The interplay of, and potential disconnects between administrative mandates, campus cultures, and the specifics of classroom implementation can have a strong impact on outcomes. They propose a model for inclusive education in universities, which encompasses all stakeholders, with their associated characteristics.

So what does this mean for our teaching practice?

Our design, delivery and assessment of learning needs to take into account our institutional context, expectations, policies and practices, and ensure that students are empowered to fulfil their potential.

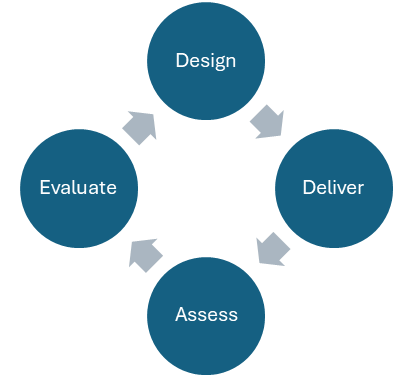

In the three sections below, we will explore inclusive design, delivery and assessment. You can read more about considerations for inclusive evaluation on the Fostering a Sense of Belonging page. In Section 4, we consider the implications for Module and Programme Design.

1: Design: Providing learning that is authentic, meaningful and relevant by recognising the needs and perspectives of all learners, and designing for all

The Cardiff University Inclusive Education Enhancement Model has a series of key targets for enhancing design which draw on research and sector recommendations.

Enhancement Model Targets for Design:

- Learning and assessment is student-centred and interactive, promoting on-going opportunities for students to make choices about the curriculum, teaching approaches and assessment practices.

- There are learning opportunities on all modules and assessments on the programme where students bring their own experiences to learning related to diversity and inclusion issues or local or international communities

There are two approaches which can enable us to develop inclusive education: Universal Design for Learning and Culturally-Sustaining Pedagogy.

Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

Moriarty (2016) suggests that the principles of UDL prompt institutions to embed anticipatory adjustments in the design of curricula that are flexible, adaptable to multiple forms of engagement and therefore facilitate all student learning. These anticipatory adjustments, by their very nature, apply to ALL students: ‘What is essential for some students is beneficial for all’.

Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy

The students in our classrooms arrive with a diverse set of learning needs and a range of cultural experiences and identities. Learning must be looked at within the context and the culture in which they occur. Culture has been defined in many ways, for example, ‘shared patterns of behaviours and interactions, cognitive constructs, and affective understanding that are learned through a process of socialization. These shared patterns identify the members of a culture group while also distinguishing those of another group’ (Hanesworth et al. 2019: 1)

Multiple levels of awareness are necessary for teachers to be culturally responsive. This includes knowledge of personal biases, students’ backgrounds/strengths, how the learning environment should build from students’ strengths; and how to bring about change in education systems.

Instructional planning using UDL is further enhanced when acknowledging how race, cultural, and linguistic differences could affect students’ learning (Kieran and Anderson 2019). The new Universal Design for Learning guidelines (2024), version 3.0, incorporate culturally sustaining pedagogies.

You can read more about these concepts on the Universal Design for Learning and Developing Inclusive Mindsets pages.

How can YOU use Inclusive Design and Universal Design for learning?

Session Design: Reflect on the student experience of learning and teaching

Go to the detailed UDL guidelines by reading them on the CAST website and identify aspects of your teaching or organisation of teaching that you would re-design to ensure you are employing universal design for learning, for each of the three areas of engagement, representation, and action and expression. You may wish to click on each bullet point for ideas which might resonate for your teaching.

Complete this Reflective Session Plan Activity:

Activity: Reflective Session Plan: Designing your teaching inclusively

Reflective Session Plan Activity

-

Write a plan for a session you might deliver.

Identify the teaching strategies used in the session, alongside the formative assessment task you will employ to demonstrate students have met the learning outcomes (this might be a quiz, feedback from discussion, or completion of practical task).

You might like to use this template:

| Title: | Duration: | |||||

| Aim: | Learning Outcomes: By the end of the workshop, participants will be able to: |

|||||

| Notes for inclusive practice and diversity: |

Location: | |||||

| Duration/Time | Teaching strategy and content |

Resource | Student Activity |

Tutor Notes |

Assessment | |

| Introduction | ||||||

| Conclusion | ||||||

2. Identify barriers to learning: Task Analysis

In order to remove barriers and inequalities in education, we firstly need to identify the barriers to learning we create in our teaching strategies, and the students who might be excluded by these practices, in order to make the changes needed to our educational practice to ensure social justice and equality. Every task we ask students to perform can create potential barriers for some students.

In the left-hand column, list the teaching activities for a session you might teach. Then in the next columns identify the student activity involved, thinking carefully about what students are actually required to do. Then list the barriers to learning that may be created, and the students who may be impacted.

An example of a face-to-face lecture is given below.

| Teaching strategy | Student activity | Barriers to learning | Students who may be impacted | Solutions |

| Face to face lectures | Listening | Cognitive processing | Students with cognitive processing issues or who are deaf | |

| Taking notes | Writing skills and speed

Large social space |

Dyslexic student. Students with English as an additional language.

Students with hypersensitivity or anxiety |

||

| Sitting for an hour | Sitting comfortably for an hour | Students with health conditions | ||

| Small group discussion with peers | Social interaction in groups | Students with autism or anxiety. |

3. Access these personas

These were created in a Cardiff University whole school inclusive education workshop. Select one or more personas to act as examples. For the persona(s) selected, identify any additional barriers to learning for these students, which have been created by the teaching strategies and assessment you have written.

4. Identify the solutions

Using the principles of UDL, identify some potential solutions to the barriers you identified in the previous reflection, by suggesting some changes to your practice.

Here is an example of some solutions to the barriers to learning identified in face-to-face lectures:

- Recording with captions provided after the session (Representation)

Recording and summary slides, videos or audio explanations of complex topics covered (Representation) - Recording or asynchronous resources provided, quiet pauses for reflection or tasks (Engagement)

Reassurance that movement or leaving the session is allowed (Engagement)

Clear instructions for group tasks, choice in who and how feed back is given, and working alone allowed (Action and expression)

5. Re-write your session plan

Apply your solutions for your personas to your plan, and note any additional considerations identified in the Tutor Notes and Notes for inclusive practice and diversity sections.

While consideration of one persona might not result in a vast number of changes, consideration of all 6 in the document might suggest a suite of changes. When applied, together these will ensure you have designed an inclusive, culturally sensitive session.

2: Supporting all students to fully participate in learning activities

‘Inclusive learning design is design that considers the full range of human diversity with its complex intersectionality. It is designing learning environments, experiences, activities, tasks, assessment and feedback with students’ voice and choice at its heart, so that students can grow academically, culturally and socially.’ (Rossi 2023)

The Cardiff University Inclusive Education Enhancement Model has a series of key targets for enhancing delivery, which draw on research and sector recommendations. You could use this as a basis for reflection and plans for improvements.

Enhancement model targets for Delivery:

- Across the programme there are opportunities for multiple means of engagement, whether face-to-face, online or asynchronous.

- The programme uses a variety of modes which are informed by different social and cultural perspectives, and build on students’ educational abilities, interests, experiences, and aspirations.

- Information, resources and materials are presented in a range of formats and regularly referred to across the programme. There are many opportunities for students to gain clarification or feedback in multiple ways.

- Visits and placements take into account the needs of all students and reflect the diversity of the student cohort.

- All virtual learning environments are fully accessible, proactive, and flexible to meet all students’ needs. The physical environment is fully accessible, and consideration is given to the accessibility of curriculum delivery. Student feedback informs the accessibility of these spaces on an annual basis.

- All modules provide reading lists which are mainly digitised, and have required and optional readings.

- Across the programme the Recording Policy is followed consistently. All materials are uploaded at least 48 hours in advance and recordings are available before the default 5 days. Students are provided with summarised notes of sessions that aren’t recorded.

- There are opportunities for students to explore and familiarise themselves with unfamiliar and new terminology and concepts are embedded in core modules across the programme.

Practical and Socio-cultural considerations for teaching

There are a wide range of considerations for the organisation and delivery of teaching spaces:

Practical

Ensure the physical environment is accessible. Check:

• physical access to buildings and spaces, and seating, meets all needs

• the room uses good lighting and colour contrast

• there is ease of movement around the room, for example, during physical transitions to activities.

• students’ physical needs, abilities and disabilities when designing practical tasks and experiments.

Ensure the digital environment is accessible (see more on this on our Digital accessibility section on the Disability and Dyslexia page). Check:

• You are following Digital Accessibility regulations when designing teaching materials, tools and assessments

• You are using accessible platforms (check for accessibility statements)

• Asynchronous and synchronous learning opportunities are available

• You provide multiple modes of content (e.g. text, audio, video)

• Students have digital competence and access, particularly when using new software or apps

• PowerPoints and other audio-visual materials are accessible (Font, background colour, use of images are supported by alt text, text is left justified)

• Use audio-described and captioned videos

• Verbalise long quotes on screen

• Articulate detail in graphs and diagrams (either verbally or provide notes)

• Check there is coherence in the way ultra pages are organised, across a module and programme

• For online learning and assessment, be aware of time differences for international learners

• Keep to time: don’t run over, and don’t gallop if time is short – record afterwards or cover later

Two key practical considerations which meet the needs of many different groups of students:

• Provide PowerPoints or other audio-visual tools available 48 hours in advance

• Make recordings of sessions available

Socio-cultural

Create an inclusive, collaborative culture which recognises students’ authentic selves, and enables them to see themselves represented in the curriculum.

Articulate learner, academic and cultural practices which may have assumed knowledge: for example, give expectations of social learning behaviours (for example, what do we DO in small group activities)

Explain any cultural references, pop culture or historical UK-centric information.

Set ground rules for differences of opinion and be aware of dynamics of power and control, between students, and with yourself and other staff

Use physical spaces which promote collaboration and social learning (e.g. room layout)

Vary activities to support multiple means of engagement and to address attention spans.

Inclusive Teaching Strategies

When planning a teaching session or series of teaching sessions, plan to use a range of teaching strategies: there is no one approach that is inclusive for all learners, as every activity will advantage some, and disadvantage others. We tend to employ ‘folk pedagogy’ (Bruner 1979) where we teach how we have been taught, and which have benefitted us as learners.

For example, a common activity in sessions is small group discussions with feedback to the larger group, which enables social, constructivist learning, and builds team working skills. However, some learners might struggle to interact in this process, due to neurodivergence, anxiety or cultural experiences of learning, if they have previously studied in different, more didactic settings. Some might therefore benefit from some time completing individual, silent reflection activities, or use of digital feedback mechanisms, such as mentimeter or padlet. Some may require clear explanations of expectations for active learning.

When planning your session, or series of sessions, plan for multiple means of engagement: you can do this within the same activity, for example, by welcoming feedback on the activity in text or oral form, or across a series of activities, by having one group work, one individual task and one digital response activity within a session. You can also ensure asynchronous engagement for those who cannot attend. In this way the variety of needs of your diverse learners can be met.

| Duration/Time | Teaching strategy and content |

Student Activity |

| 10 mins | Introduction: Teacher talk | Listen and take notes (didactic teaching of core content, slides, readings and notes available in advance and afterwards) |

| 20 mins | Group activity: Apply talk to practice | Group discussion with feedback via oral presentation or mentimeter (social learning with choice of feedback mode, available asynchronously) |

| 10 minutes | Introduce individual activity: Silent reflection and 1 minute summary | Listen to or read introduction to task, reflect and write 1 minute summary (choice of modes for instructions for activity) |

| 10 minutes | Conclusion: Mentimeter Quiz and summary | Complete quiz online (multi-media for range of activities, can be completed asynchronously) |

For further reading: Bale and Seabrook (2021) consider a range of inclusive teaching strategies in their book ‘An introduction to university teaching’, including small and large group teaching, lab work, fieldwork and digital education.

Here are 4 top tips from Cardiff University students:

The power of talk

Student 1: ‘ I felt more confident when lecturers encouraged questions and discussions.’

Let's meet

Student 1: 'Having one-to-one meetings with my tutor helped me identify areas for improvement.'

Student 2: ‘Feedback is where students can truly grow, especially when they know you're invested in their development. Students are smart; if they sense that you're giving feedback not just as a tick-box exercise but because you genuinely want to help them improve, they respond with more effort and engagement. I’ve seen this time and time again. Timely, constructive feedback isn't just a teaching obligation, it’s one of the most powerful tools we have to support student success’

Press record

Student 1: 'Online recorded lectures allowed me to revisit difficult topics.'

Make it flexible.

Student 1: 'Multiple means of engagement offered, including doing the task slightly differently so its possible.'

Student 2: ‘Having experienced a blended learning environment, I feel that it is the most beneficial to as many different students as possible, owing to its flexibility and adaptability.’

Below is a short listen and a case study to further your application to practice :

Case Study: Inclusive Practical Experiments

Considerations for Inclusive Education in Experiments and Laboratory Settings (Anna Richards, Biosciences):

- Teaching Strategy: Demonstration and observation of a practical laboratory technique

Student Activity

Read and understand a protocol, observe practical demonstration of a particular technique, take notes, stand for up to several hours, small, instructor-led group discussion to ask questions

Barriers to Learning

Cognitive and/or sensory processing, physical discomfort, limited visibility or access, language or communication issues

Students who may be impacted

Students with visual, auditory or cognitive impairments; Students with health conditions, particularly mobility issues, chronic pain, or disabilities; Dyslexic students;

Students with English as an additional language

Solutions

- Break down the protocol and technique into smaller, manageable steps.

- Provide pre-session reading materials that explain the theory and steps of the technique in simpler terms.

- Use diagrams, videos, or animations before the demonstration to visually represent complex steps.

- Allow for frequent breaks during long demonstrations to reduce fatigue from standing.

- Provide seating options for students who cannot stand for extended periods.

- Use visual aids, such as overhead cameras or screens, to project the demonstration clearly so everyone can see it.

- Teaching Strategy: Simulations or Virtual Labs

Student Activity

Navigate the virtual environment, follow a virtual protocol or introductory exercise, collect and analyse simulated data, collaborative work in virtual teams.

Barriers to Learning

Technical difficulties or lack of technical proficiency; Cognitive and/or sensory processing; Motivation and Engagement due to a more abstract, less interactive session.

Students who may be impacted

Students with visual, auditory or cognitive impairments; Students with limited access to technology; Dyslexic students; Students with English as an additional language.

Solutions

- Provide a pre-lab tutorial or training session on how to use the virtual lab platform (e.g. video tutorials, step-by-step guides, or interactive walkthroughs)

- Offer technical support during the lab session, such as a dedicated help desk or teaching assistants available to troubleshoot issues.

- Simplify protocols by breaking them into smaller, manageable steps, and provide visual aids or animations that explain each step of the virtual procedure.

- Design the virtual protocol to allow students to pause and revisit sections if they feel overwhelmed, giving them control over the pace of the exercise

- Teaching Strategy: Problem-Based Learning group work

Student Activity

Work through a real-world problem scenario related to the lab activity. Use critical thinking, teamwork and independent enquiry to plan and conduct an experiment addressing a case provided by the instructor.

Barriers to Learning

Technical skills and speed; Social interaction in groups and working effectively with others; Physical discomfort; Limited visibility or access

Students who may be impacted

Novice/inexperienced learners; Students with less confidence/anxiety; Students with cognitive or processing challenges (e.g., dyslexia, ADHD, autism); Students with physical disabilities or chronic health conditions; Students with visual, auditory or cognitive impairments

Solutions

- Offer comprehensive workshops or tutorials before the lab session and provide clear, written protocols with visual aids, flowcharts, or videos that students can refer to during the lab

- Implement a peer mentoring system where more experienced students can assist those who are less confident or skilled.

- Assign specific roles within groups to ensure balanced participation and accountability.

- Schedule regular breaks during lab sessions to allow students to rest and stretch.

- Arrange seating and lab stations to ensure that all students have clear visibility of demonstrations and equipment

3: Assess: Enabling all students to demonstrate their abilities, skills and knowledge: Assessment and Universal Design for Learning

Key Considerations for Inclusive Assessment at Cardiff University

The Cardiff University Inclusive Education Enhancement Model has a series of key targets for enhancing assessment, which draw on the sector recommendations outlined above. See more about implementing this in our Programme Design section, below.

Enhancement Model Targets for Assessment at a Session or Module Level:

- Modules provide learning activities and formative assessments that build students’ skills and understanding in the discipline ready for summative assessments.

- Module team(s) design and review assessments to ensure no obvious barriers to learning are created for groups of students and anticipate barriers by applying Universal Design for Learning principles to help ‘design out ‘ the need for individual adjustments.

- Assignment briefs, criteria and guidance are well designed, and all students are clear of the requirements and understand expectations of a high grade.

- Most modules plan alternative assessments from the outset providing assessment criteria and eligibility to all students.

- Module teams agree a feedback strategy and terminology to be used in feedback. Feedback is personalised to the content, and is clear and concise, relates to assessment criteria and is constructive and actionable.

Re-thinking Assessment at Cardiff University

Inclusive Assessment is a key consideration of the university-wide Rethinking Assessment Project and the Strategic approach to Assessment, so consideration of this is also very useful when thinking about assessment.

Principles

In order for HE institutions to comply with the Equalities Act 2010, when considering assessment, institutions should design assessments that are both anticipatory and inclusive. Inclusive universally designed assessment processes provide for all students whilst also meeting the needs of specific groups.

There are a series of specific recommendations for the programme-level design of inclusive assessment (Advance HE 2018: Tai et al. 2019). Programmes should employ:

- A range of assessment approaches that are accessible, non-discriminatory and timely.

- A range of feedback approaches that are accessible, interactive, ongoing and timely.

- Incorporation of student choice in assessment practices.

- Opportunities to critically engage with equality, diversity and inclusivity themes in assessments that relate to authentic real life scenarios.

- Preparation, engagement and support of students throughout the assessment process that develops their assessment literacy.

- Opportunities for students to act as partners in the assessment and feedback process.

- A programme-level approach to the design, development, understanding and coordination of assessment and feedback practices.

- Routine monitoring, review and sharing of assessment practices that embed equality, diversity and inclusivity.

The students perspective on assessment practices and grading policies:

Student 1

It’s important to provide students with clear, detailed information about how grades are assigned, and the criteria used. This transparency reduces confusion and allows students to focus on what’s expected for success. At the same time, it's worth acknowledging that not all forms of assessment flexibility are possible, particularly in disciplines like medicine and healthcare, where assessment structures are often governed by external regulatory bodies.’

Student 2

‘When I got feedback on my first essay, I was unaware that it is very normal for first-year UG students to receive marks that are in and around the 50s/60s. I was used to seeing very different numbers from my A-Level studies, so again, I wish this information had been circulated to prospective students, and that a Q&A-style session had been organised to address this shift in grading.’

Student 3

‘I would recommend that lecturers make the link between assessments and learning outcomes clear. One thing I've found really helps students is being crystal clear about why they're doing this dissection session and how it ties into the learning outcomes by linking to clinical cases. When students understand what’s expected and how it connects to the bigger picture, they’re more focused and less anxious. Even just taking a bit of time to walk them through the marking criteria and showing an example or two of what “good” looks like can go a long way.’

Student 4

‘My lecturers providing clear and effective learning outcomes helps me in understanding the key topics and plan my revision around those’

Assessment and Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy

As a social construct, assessment could be said to comprise practices and processes in which specific values and practices are reflected and enshrined, such as (in the UK at least) rationality, individuality, objectivity and written capabilities. Recent work on inclusion and universal design of assessment has focussed on the imperative to consider the socially constructed nature of assessment, through the lens of Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy (CSP) (Hanesworth et al. 2019).

Assessment forms and practices are created through unquestioned and habitual use, are normalised and can marginalise and exclude certain students and cohorts for whom such practices are unfamiliar or inaccessible.

Assessment can also be seen to hierarchise knowledge: in our inevitable selection of content for assessments, we subconsciously communicate to learners what disciplinary knowledge is important or valuable, and what is not. Assessment is indivisible from individual value judgements: designed and evaluated by us, with all our complex socio-cultural backgrounds, educational experiences and intellectual and personal values. It is therefore subject to our biases.

Learn about the use of UDL in assessment in the University of Limerick:

Inclusion implications of different assessment types

For consideration of the challenges and solutions provided by particular assessment types, see the Assessment Compendium page, which details over 20 different forms of assessment, with comments on the barriers to learning for each assessment, and considerations in terms of addressing inclusivity.

Reasonable Adjustments for Disabled Students

We have a duty under the Equality Act to make reasonable adjustments to our assessments, for disabled students, once agreed by the School. There is a specific policy and guidance for staff teaching undergraduate and PGR students to support you in this.

Reasonable adjustments should not compromise the academic standards of programmes or modules, as the Equality Act places no duty to make a reasonable adjustment to a competence standard. A competence standard is ‘an academic, medical, or other standard, applied for the purpose of determining whether a person has a particular level of competence or ability’. A competence standard must apply equally to all students, be genuinely relevant to the programme, and be a proportionate means to achieving a legitimate aim.

There is however a duty to make reasonable adjustments to the way in which a competence standard is assessed so that disabled students are not disadvantaged as a result of their disability. Reasonable adjustments must not affect the validity or reliability of the assessment outcomes. However, they may involve, for example, changing the usual assessment arrangements or method, adapting assessment materials, providing a scribe or reader in the assessment, and re-organising the assessment environment

Alternative Assessments

Alternative Assessments are provided when, for some reason, a student cannot complete the assessment designed for the module or programme. This might be because of a disability, and be the reasonable adjustment required. Alternatively, it might be because of a short-term issue for the student, for example sudden ill health or bereavement, requiring an alternative remedy.

When designing your module, consider what alternative assessments might be required in these scenarios, and design these from the outset. This ensures you are being anticipatory in your design to comply with the Equality Act. Ensure you prepare assessment guides, marking criteria or rubrics for all forms of assessment, and explain the eligibility for alternative assessments to students.

Choice in Assessment Mode

Choice in assessment can take many forms: choice of topic, modes (such as written, presentation, multi-media) or scope, such as individual or team work. While choice of topic may be more familiar, the option of choice in mode or scope has been seen as more challenging to our organisational structures and processes, despite the potential to provide for Universal Design for Learning through multiple means of action and expression.

Recent post-pandemic publications support choice in assessment, highlighting how positive changes made during the pandemic enabled the introduction of diversity and choice in assessment, and exploring how these might be sustainable in the future through changes to assessment principles and practices, and through collaborating on a programmatic approach to assessment (Padden and O’Neil 2021).

In relation to student choice in assessment mode, research highlights the complexity of issues surrounding the implementation of student choice in relation to: equity, perception of staff and students, careful and transparent alignment and impact on outcomes, programme requirements and professional body standards.

Despite these complexities, O’Neil (2017) highlighted the positive impact of a limited choice for students, with the attainment of higher grades than those achieved by previous student cohorts who did not experience choice. Similarly, Hockings’ seminal review of the literature (2010: 21) suggested that having choice in assessment mode enables students to deliver evidence of their learning in a medium that suits their needs, rather than in a predetermined and prescribed format, which may disadvantage an individual or group of students in the cohort. Research on student choice in assessment by Cardiff University highlighted similar themes (Morris, Milton and Goldstone 2019).

Cardiff University is currently conducting a pilot project on the implementation of Choice of Assessment, with a view to implementation in 2025/6 academic year.

Here you will find the students perspective on the value of assessment choice:

Student 1

‘I also value the emphasis on offering diverse types of assessments. As someone who doesn’t always perform best in traditional written exams, it’s encouraging to see a recognition that students have different strengths. Having a mix of written, oral, and practical assessments can make a huge difference in helping everyone demonstrate their knowledge in a way that suits them.’

Student 2

‘From my experience, I would also strongly recommend using a mix of assessment methods wherever possible. Not every student excels in the same format, some perform well in written exams, while others thrive in presentations or practical tasks. When the course structure allows, offering a variety of assessment types can really help level the playing field. I’ve seen first-hand how this can increase student engagement and boost confidence, particularly for those who may find traditional formats more challenging.’

Inclusive Programme Design

- Inclusive Programme Scoping

We have a responsibility under the Equality Act 2010 to anticipate the needs of prospective, future students. In addition, one of the goals of the university’s Widening Participation strategy is: To attract and recruit students with academic potential, regardless of background or personal experience. When scoping a new programme, it is important to pay attention to diversity dimensions and the potential barriers to enrolment for those from under-represented groups, which may be created by the processes, procedures and practices of recruitment and selection (You can read more about these concepts on the Introduction to Inclusive Education page, and in this document from the EHRC (which outlines your legal responsibilities ), and in Advance HE also have produced comprehensive guidance on equitable student recruitment and admissions and your legal responsibilities.

Being aware of the diversity dimensions of current students in your School can help to identify areas of disparity, to inform programme design and planning, and to act as a baseline for measurement for future improvements. Access this Sway for a snapshot of diversity characteristics of all students in Cardiff University from November 2024, which may give you unexpected insights into the diversity characteristics of our students. You can obtain programme-level data on diversity characteristics through Business Objects.

2. Inclusive Programme Design

This page presumes an understanding of writing basic learning outcomes. To refresh your understanding, click on the title below, to access a summary of the process.

Writing Effective Programme Learning Outcomes

Learning outcomes are normally made up of three elements.

- A verb to define the specific action that students will do to demonstrate their learning.

- A subject, to specify the subject material you want the learning to cover.

- The context of the learning. While learning outcomes do not need to explicitly refer to particular methods of assessment, they should include an indication of the standard of the performance that will demonstrate that the defined learning has been achieved. It should therefore be clear what a student needs to learn/do to attain that learning outcome.

Let’s see that in practical terms:

- An action that can be verified empirically, by ‘the evidence of your eyes and ears’;

- A subject: the given;

- Performance criteria which contextualises the learning.

Examples:

- Analyse the relationship between the language of satire and literary form by the close examination of a selected number of eighteenth-century texts in a written essay.

- Compile a research paper which encompasses a wide range of relevant methodologies and resources.

- Demonstrate a critical understanding of the technological aspects of imaging modalities, including the use of pharmacological agents, to assist with the procedures.

- Design and prepare a clear and coherently structured written presentation about the biography of a building or site.

Intended outcomes should always be SMART and assessable, so their wording needs to reflect the specific knowledge, skills and behaviours students should be able to demonstrate on successful completion of the programme. For example, while we may need students to ‘understand’ a concept, we need to frame the learning outcome in terms of what are they going to do, to demonstrate that they have understood.

Writing Inclusive Programme Learning Outcomes

When designing Programme Learning Outcomes (PLOs), you are creating the conditions by which all students will be assessed, whatever their dimensions of diversity or characteristics. It is therefore essential that you identify the competence standards of the programme, and the academic standards, and that you write your learning outcomes in such a way that maximises flexibility, choice and equity in your assessments, to avoid unintended institutionalised discrimination.

Writing inclusive Programme Learning Outcomes ensures all students can demonstrate what they know, or can do, to enable them to meet the learning outcomes to their potential. This useful video from the Bologna Agreement group explains more.

Universal Design and Inclusive Programme Learning Outcomes

The new Universal Design for Learning Guidance can also help us frame our Programme Learning Outcomes, particularly in relation to Multiple Means of action and expression, as learners differ in the ways they navigate a learning environment, approach the learning process, and express what they know. Click on the heading for prompts for reflection during the design process, or visit our Universal Design for Learning page for more information.

Multiple Means of Action and Expression for Programme Learning Outcomes

It is essential to design for varying forms of action and expression. For example, all individuals approach learning tasks very differently, and may prefer to express themselves in written text but not speech, and vice versa. It may not always be feasible to build in multiple options or choices for every activity or assessment, if a competence standard must be reached, but there should be diversity in assessment mode, as far as possible.

It should also be recognised that action and expression require a great deal of strategy, practice, and organisation, and this is another area in which learners will differ. In reality, there is not one means of action and expression that will be optimal for every learner; options for action and expression are essential.

Think about how learners are expected to act and express themselves. Design options that:

- Enable variety in interactions in responses, navigation, and movement, and enable options in interactions using accessible materials and assistive and accessible technologies and tools

- Provide options and flexibility for students in the expression and communication of their learning, through multiple media and multiple tools for construction, composition, and creativity, challenging exclusionary practices

- Build fluencies with graduated support for practice and performance, addressing biases related to modes of expression and communication

- Support students in strategy development and the setting of meaningful goals, enabling students to anticipate and plan for challenges and organise information and resources

Reflection: Do you design for:

- Choice or flexibility in responses, interactions, activities and collaborations within sessions?

- A range of accessible resources, tools and technologies for expression of learning

- Choice or flexibility in the mode students can demonstrate their knowledge or skills, such as written, spoken or multi-media?

- Scaffolded support for students to demonstrate essential skills in a particular mode, for example practice runs, formative tasks and clear criteria for skills as well as content?

- Support for goal setting, strategic planning, time-management and management of information, such as module and assessment maps, session plans and summaries of information resources?

PLOs and Reasonable Adjustments

You have a responsibility to clearly define the competence standards for the programme, before writing the PLOs, to ensure that students with Reasonable Adjustments for assessments under the Equality Act provisions for disabled students can achieve. Reasonable adjustments cannot compromise the competence standards of programmes or modules, as the Equality Act places no duty to make a reasonable adjustment to a competence standard. A competence standard is ‘an academic, medical, or other standard, applied for the purpose of determining whether a person has a particular level of competence or ability’. A competence standard must apply equally to all students, be genuinely relevant to the programme, and be a proportionate means to achieving a legitimate aim.

In Universal Design for Learning, competence standards have been framed as ‘construct relevance’:

There is a duty to make reasonable adjustments to the way in which a competence standard is assessed so that disabled students are not disadvantaged as a result of their disability. Reasonable adjustments must not affect the validity or reliability of the assessment outcomes. However, they may involve, for example, changing the usual assessment arrangements or method, adapting assessment materials, providing a scribe or reader in the assessment, or re-organising the assessment environment.

More guidance and the Policy and Procedure for Reasonable Adjustments for Disabled Students can be found on the Cardiff University intranet. There have been recent legal developments in this area in 2024, with guidance produced by the Equality and Human Rights Commission: it is recommended that you read this before writing your PLOs.

Creating Inclusive Learning Outcomes: A worked example:

Returning to an earlier example of learning outcomes, from the refresher section above:

- Analyse the relationship between the language of satire and literary form by the close examination of a selected number of eighteenth-century texts in a written essay.

You would firstly decide if a written essay is a competence standard for this programme: Is this an essential skill? Could the student demonstrate their learning in another mode, such as an oral presentation?

The EHRC states that universities must ‘ensure that academic staff setting assessments know which aspects of their test are competence standards which must be met, and which aspects are the methods of assessment which may be reasonably adjusted’.

Thus, if it can be justified that a written analysis is a core competence for this programme, then the learning outcome can remain. Otherwise, the performance criteria could be re-phrased to enable multiple modes of action and expression (using the principles of Universal Design for Learning), with the student being able to complete an oral or written analysis. You might also specify the number of texts, to clarify expectations for students. For example:

- Analyse the relationship between the language of satire and literary form by the close examination of twelve eighteenth-century texts using your preferred mode of submission, from either a recorded oral presentation or a written essay.

3. Inclusive Assessment and Feedback

Inclusive Assessment Strategy Considerations

In the Cardiff University Enahancement Model, and the Inclusive Education Framework (2023), a series of considerations are highlighted for programme teams for assessment and feedback:

| Our programme team ensure that: |

| Our assessment is designed at programme level, giving students a manageable assessment workload and minimising clashes of hand-in dates |

| Our programme uses a range of assessment formats, and enables student personalisation choice of assessment format where appropriate |

| Our students have had an opportunity to practice all final year summative assessment types earlier in the programme, and understand the relationships between assessments at different levels |

| Our assessments are clearly explained to students through module documentation, written materials and activities in class, using transparent and consistent language to make requirements clear |

| Our assessments design out the need for individual alternatives wherever possible (e.g. students given the choice of audio/visual formats so students with hearing/visual impairments do not require individual alternative assessment) |

| Our mark schemes are clearly linked to learning outcomes or competencies to ensure marking is appropriate and consistent with assessment design |

| Our mark schemes do not over-penalise mistakes in written English or referencing conventions |

| Markers’ feedback comments are constructive, and actively point out ways that students can improve their work for future assignments. |

| Markers provide relevant, focussed and timely formative feedback to support student learning |

| Our programme team are sensitive to student anxieties around assessment and feedback, so create a supportive culture around assessment, provide clear guidance, and offer opportunities for students to voice concerns |

To consider the inclusivity of your assessments:

Map your assessments to the Programme Learning Outcomes

- Identify any challenges for diversity: are there any particular forms of assessment which are over-represented (for example written vs speech, exam vs coursework)? (see Inclusive Programme Assessment Mapping, below).

Map your assessments by student journey

- Identify: bunching, early and low stakes preparation for assessment types, potential options for adding choice in assessment, and adequate support for new or innovative assessment types. Consider what might be offered as alternative assessments for students with Reasonable Adjustments due to disability, if inclusive design is not available due to competence standards.

Map the socially-constructed nature of your assessments:

- Assessment practices can be created through the use of ‘folk pedagogy’, using unquestioned and habitual forms, which are normalised and can marginalise and exclude certain students for whom such practices are unfamiliar and inaccessible. Analyse your assessments through the lens of Universal Design for Learning and Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy (CSP) (Hanesworth et al. 2019), being aware that we may use familiar practices (such as the domination of the written essay in UK universities), over those more familiar in other countries (such as oral examination or group work). You can read more about this on the Universal Design for Learning page.

Inclusive Programme Assessment Mapping

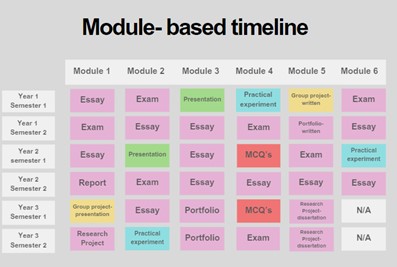

To map the inclusivity of assessments on a programme, we need to apply the principles of Universal Design for Learning in enabling students multiple means of action and expression. Identifying the modes of assessment across a programme enables us to analyse the range of different modes of assessment offered, and the potential barriers to attainment for groups of students. If analysed as a colour coded module-based timeline, the dominance and flow of modes of assessment becomes apparent:

Figure: A module-based timeline of modes of assessment.

This approach enables us to see in this example that there is a reasonable range of assessment modes across the programme, with some oral, digital and practical forms of assessment. However semester 2 in years one and two all use written modes of assessment: dyslexic students, or those with English as an additional language, might find this more challenging. Oral forms of assessment create less barriers to learning than these academic written assessment modes for these students, so a change to one or two of these assessment modes would be more equitable for your diverse students.

In terms of progression, presentations are usefully introduced in the first year before higher-stakes presentation assessments in later years. However MCQs (multiple choice questions) are not introduced in year 1, and the research project of the dissertation could be supported by earlier, smaller research projects in years 1 and/or 2.

4. Inclusive Programme Delivery

Programme Delivery

A key concern for programme delivery is the need to maintain consistency and equity across modules and elements of a programme, to ensure clarity and fairness for students. Research suggests a lack of programmatic initiatives for inclusive education, with most positive changes for diverse students evident at the ‘coal-face’ of teaching, in learning spaces and interactions between individual teachers and students (Lawrie et al. 2017)

Once a programme is launched, it is essential that all module leads, lecturers and other supporting staff are aware of the inclusive principles behind your programme design, learning outcomes and assessments, and that they have a clear set of inclusive principles to follow in their module design and teaching practices.

Essential considerations are

- Module learning outcomes are designed to map to programme learning outcomes, and are written following the inclusive learning outcomes principles, above.

- Module assessments are designed to offer a range of assessment modes, flexibility and choice where possible, and scaffolded support where needed.

- Module principles are followed for

- the development of resources (such as identical structuring of all Learning Central module pages on a programme, to aid students with navigation)

- provision of resources (such as providing resources 48 hours in advance, and standard provision of recordings or notes on sessions)

- opportunities for support and queries (such as having a standard approach to both in-person, asynchronous and anonymous queries on all modules).

- Module principles are outlined for the expectations of lecturers during teaching sessions, which enhance students’ sense of belonging, respect for diversity and opportunities for use of multiple means of representation and engagement.

It is recommended that Programme Leads co-construct, design and distribute an Inclusive Education Principles guidance document to all module leads, to ensure there is consistency and parity for students throughout their experience of the programme. Further, regular monitoring and evaluation of modules to ensure these principles are enacted and embedded is essential.

Programme Evaluation and Learning Enhancement

When monitoring, evaluating or reflecting on the inclusivity of your programme, consider the student experience, and the operational and pedagogical design of sessions and modules

- Ensure you gather the voices of all students, through a range of reflection and evaluation techniques. Advance HE has detailed guidance on the collection and monitoring of diversity.

- Also consider how you will gather the evaluations and opinions of groups who are often marginalised or excluded from traditional student evaluation, co-construction and partnership activities, to ensure you respect and gather the voices of all. Many of our most disadvantaged students are time-poor and have less opportunity to engage in these types of activities, so ensure collaboration, co-construction and evaluation can be completed asynchronously, and in a range of modes, such as in oral or written form.

- You can also use self-reflection: monitor and evaluate your programme for inclusive education using the Cardiff University Inclusive Education Enhancement Model, or The Inclusive Higher Education Framework and Toolkit, which has specific resources for programme design, and is a collaboration between University of Hull, University of Derby, Keele University, Staffordshire University and York St John University.

References

Advance HE 2018. Embedding EDI in the Curriculum: A programme standard. Online. Available at: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2019-09/Assessing%20EDI%20in%20the%20Curriculum%20-%20Programme%20Standard.pdf

Bass, G. and Lawrence-Riddell, M. 2020. Culturally Responsive Teaching and UDL https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/equality-inclusion-and-diversity/culturally-responsive-teaching-and-udl/

CAST. 2024. Universal Design for Learning Guidelines. Available at: https://udlguidelines.cast.org/

CAST 2018. UDL and Assessment. http://udloncampus.cast.org/page/assessment_udl

Fovet, F. (2020) Universal Design for Learning as a Tool for Inclusion in the Higher Education Classroom: Tips for the Next Decade of Implementation. Education Journal, 9(6), 163-172

Hanesworth, P. Seán Bracken & Sam Elkington (2019) A typology for a social justice approach to assessment: learning from universal design and culturally sustaining pedagogy, Teaching in Higher Education, 24:1, 98-114, DOI: 10.1080/13562517.2018.1465405

Hockings, C. 2010. Inclusive Learning and Teaching in Higher Education: A Synthesis of Research. York: Higher Education Academy.

Kieran, L. and Anderson, C. 2018. Connecting Universal Design for Learning With Culturally Responsive Teaching Education and Urban Society 2019, Vol. 51(9) 1202–1216

Lawrie, G., Marquis, E., Fuller, E., Newman, T., Qui, M., Nomikoudis, M., Roelofs, F., & van Dam, L. (2017) Moving towards inclusive learning and teaching: A synthesis of recent literature. Teaching and Learning Inquiry 5 (1)

Kwak 2020. Culturally Responsive Teaching in Higher Education. Online. Available at: https://www.everylearnereverywhere.org/blog/culturally-responsive-teaching-in-higher-ed/

Moriarty, A. and Scarffe, P. 2019. Universal Design for Learning and Strategic Leadership. In: Bracken, S. and Novak, K. Transforming Higher Education through Universal Design for Learning: An international perspective. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge

Morris, C. Milton, E. and Goldstone, R. 2019 Case study: suggesting choice: inclusive assessment processes, Higher Education Pedagogies, 4:1, 435-447

O’Neil, G. (2017). It’s not fair! Students and staff views on the equity of the procedures and outcomes of students’ choice of assessment methods. Irish Educational Studies, 36(2), 221–236

Padden, L. and O’Neill, G. 2021. Embedding equity and inclusion in higher education assessment strategies: creating and sustaining positive change in the post-pandemic era. In: Baughan, B. 2021. Assessment and Feedback in a Post-Pandemic Era: A Time for Learning and Inclusion. Advance HE: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/assessment-and-feedback-post-pandemic-era-time-learning-and-inclusion

Parsons, L and Ozaki, C.C. 2020. Teaching and Learning for Social Justice and Equity in Higher Education. Switzerland: Springer

Rossi, V. 2023 Supporting Student Success: Inclusive Design. https://www.london.ac.uk/centre-online-distance-education/blog/supporting

Tai, J. et al. 2022. Assessment for inclusion: rethinking contemporary strategies in assessment design. Higher Education Research and Development (Online)

Recording of the Page

Deeper Dives

Case study: Gemma Peterson, Senior Manager Employability Enterprise Learning Resources, Student Futures

Choice in assessment

The aim of the Independent Fashion Communication Project (IFCP) module was to consolidate prior learning, allowing students to choose and focus on a particular area of study. This module was the final project set at level 6 for undergraduate students studying a BA(Hons) on a two-year intensive course.

The creation of the module played to the individuals’ strengths, increasing confidence, autonomy and engagement, by giving the student choice over the project content and outcome for assessment.

Students were provided with a template for the module brief, with a set word count, guidance for submission and choices for assessment.

The final project was informed by research undertaken during the dissertation which further enhanced their academic skills and professional attributes including project management, commercial awareness and sustainability related themes.

The outcome was the creation of a high-quality piece of work that emulated industry standards and utilised industry technologies. The work also aligned with their future aspirations and career goals, forming a portfolio that could be evidenced at interviews, both for employment or post graduate studies.

There were consistent elements; the ‘process’ of writing the project brief and delivering an initial ‘pitch’ of the project were fixed elements for assessment. These were crucial in creating the ‘contract’ of study with the student when drafting the project. The project outcomes would be assessed on the students’ ability to action the ‘agreed’ outcomes of the brief so a rubrik was used to assess and ensure regulatory standards were maintained.

Assessing the work was exciting and no longer monotonous as all projects varied which equally reduced the opportunity to copy or plagiarise.

Engagement was increased due to the level of interest and direction in which the student had chosen. *The module that ran prior to this was focused on the future employment of their chosen industry sector, so students had already established an idea of where they would like to focus their project. A personal interest in the subject aided their want to succeed and complete, especially during the final stages of the project and degree. Accountability for the success of the project also resided with the student. This was incredibly useful if grades were contested. The onus was with the student having committed to agreed project outcomes by an agreed date, with the rubrik for assessment shared with students from the offset.

*The students could also choose to develop a concept, idea, project from previous study that would act as the preliminary research stages to avoid any plagiarism and duplication for assessment. All new materials and content were essential and were made explicit.

What next?

If someone were thinking of doing something similar, I would say do it! Perhaps introduce the ‘choice’ earlier in the curriculum so that it is not an unexpected process but something that is steadily increased and encouraged; students become familiar with the opportunity.

Tutorials were critical in supporting the continual development and direction of each student. These were optional and students could sign up to dates ahead of schedule that would work with their project dates, development, progress, etc.

Tutors or mentors were assigned students based on their subject knowledge, expertise and or industry ties. This could be an opportunity to bring in experts from industry or from across the schools, colleges within Cardiff University, increasing interdisciplinary discussions and outcomes.

Recording of Case Study

Where Next?

The Inclusive Education CPD Offer

Toolkit

You can now develop your understanding of Inclusive Education by accessing the related pages on specific topics, outlined in the map below, which relate to the Inclusive Education Framework. After accessing this page, we recommend you move to the Developing Inclusive mindsets page. However you can jump to any useful topic, as you require.

Workshops

You can also develop your understanding of Inclusive Education by attending workshop sessions that relate to each topic. These workshops can be taken in a live face-to-face session, if you prefer social interactive learning, or can be completed asynchronously in your own time, if preferred. You can find out more information on workshops, and the link to book is here.

Bespoke School Provision

We offer support for Schools on Inclusive Education, through the Education Development service. This can be useful to address specific local concerns, to upskill whole teams, or to support the programme approval and revalidation process. Please contact your School’s Education Development Team contact for more information.

Map of Topics

Below is a map of the toolkit and workshop topics, to aid your navigation. These will be developed and added to in future iterations of this toolkit.

You’re on page 4 of 8 Inclusivity theme pages. Explore the others here:

1.Inclusivity and the CU Inclusive Education Framework

2.Introduction to Inclusive Education

3.Fostering a sense of belonging for all students

4.Empowering Students to Fulfil their potential

5.Developing inclusive mindsets

6.Universal Design for Learning

8.Disability and Reasonable adjustments

Or how about another theme?

Recording of the page

References

Advance HE 2018. Embedding EDI in the Curriculum: A programme standard. Online. Available at: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2019-09/Assessing%20EDI%20in%20the%20Curriculum%20-%20Programme%20Standard.pdf

Bass, G. and Lawrence-Riddell, M. 2020. Culturally Responsive Teaching and UDL https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/equality-inclusion-and-diversity/culturally-responsive-teaching-and-udl/

CAST. 2021. Universal Design for Learning Guidelines. Available at: https://www.cast.org/impact/universal-design-for-learning-udl

CAST 2018. UDL and Assessment. http://udloncampus.cast.org/page/assessment_udl

Fovet, F. (2020) Universal Design for Learning as a Tool for Inclusion in the Higher Education Classroom: Tips for the Next Decade of Implementation. Education Journal, 9(6), 163-172

Hanesworth, P. Seán Bracken & Sam Elkington (2019) A typology for a social justice approach to assessment: learning from universal design and culturally sustaining pedagogy, Teaching in Higher Education, 24:1, 98-114, DOI: 10.1080/13562517.2018.1465405

Hockings, C. 2010. Inclusive Learning and Teaching in Higher Education: A Synthesis of Research. York: Higher Education Academy.

Kieran, L. and Anderson, C. 2018. Connecting Universal Design for Learning With Culturally Responsive Teaching Education and Urban Society 2019, Vol. 51(9) 1202–1216

Lawrie, G., Marquis, E., Fuller, E., Newman, T., Qui, M., Nomikoudis, M., Roelofs, F., & van Dam, L. (2017) Moving towards inclusive learning and teaching: A synthesis of recent literature. Teaching and Learning Inquiry 5 (1)

Kwak 2020. Culturally Responsive Teaching in Higher Education. Online. Available at: https://www.everylearnereverywhere.org/blog/culturally-responsive-teaching-in-higher-ed/

Lilley, M. Pyper, A. and Attwood, S. 2012. Understanding the Student Experience through the Use of Personas, Innovation in Teaching and Learning in Information and Computer Sciences, 11:1, 4-13

Moriarty, A. and Scarffe, P. 2019. Universal Design for Learning and Strategic Leadership. In: Bracken, S. and Novak, K. Transforming Higher Education through Universal Design for Learning: An international perspective. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge

Morris, C. Milton, E. and Goldstone, R. 2019 Case study: suggesting choice: inclusive assessment processes, Higher Education Pedagogies, 4:1, 435-447

Padden, L. and O’Neill, G. 2021. Embedding equity and inclusion in higher education assessment strategies: creating and sustaining positive change in the post-pandemic era. In: Baughan, B. 2021. Assessment and Feedback in a Post-Pandemic Era: A Time for Learning and Inclusion. Advance HE: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/assessment-and-feedback-post-pandemic-era-time-learning-and-inclusion

Parsons, L and Ozaki, C.C. 2020. Teaching and Learning for Social Justice and Equity in Higher Education. Switzerland: Springer

Rossi, V. 2023 Supporting Student Success: Inclusive Design. https://www.london.ac.uk/centre-online-distance-education/blog/supporting

Rowan, L. 2019. Higher Education and Social Justice The Transformative Potential of University Teaching and the Power of Educational Paradox Cham : Springer International Publishing

Tai, J. et al. 2022. Assessment for inclusion: rethinking contemporary strategies in assessment design. Higher Education Research and Development (Online)

Share Your Feedback