Linguistic Understanding

Not all international students will face a linguistic challenge, and some only to a lesser extent (Bell, 2016). However, for most international students, language proficiency is the biggest challenge when adjusting to UK university life (Sawir, 2005 and Burdett & Crossman ,2012).

Key research on the role of linguistic proficiency and the challenges international students face, (Gatwiri G. 2015);

There is a discourse about whether traditional standardised language tests and grammar methods inadequately prepare students (Wu and Hammond 2011). Even when students’ English language skills are good when they arrive at university, they find that their linguistic proficiency is insufficient to cope with the demands of an English-speaking environment. Challenges also lie in the subtleties embraced by academic writing. The level of language competence to identify these differences and model them in their writing can be demanding. Reviewing sources for reliability and validity and the language used and context can be less accessible to students creating barriers for those students who are not English first language speakers. (Ramachandran 2011: Ecohard and Fatheringham 2017). It is not just the academic language proficiencies that can cause a challenge but the communication with native speakers and the pace of the speaker, dialect, accent, and use of idioms and metaphors that are culturally dependent can create a sense of isolation that can impact both academic and socio-cultural integration. (Wu and Hammad 2011, Akanwa 2015).

Considerations need to be made about:

• How English was taught in the home country and to what level of acquisition, the application of informal English in the UK, the use of idioms, metaphors, and culturally specific references, and lastly the specific academic language associated with the discipline.

• Whether the student has learned English from a native English speaker or someone who has English as an additional language (Ramachandran 2011).

Many nuanced factors contribute to how a student acquires language and it would be unrealistic to expect international students to arrive in the UK using fluent English, and a knowledge of contextual references, metaphors, and idioms to communicate effectively (Echochard and Fotheringham 2017). This view undermines the complex nature of applied linguistics and acquiring another language. Many international students choose to study in the UK as they understand the value of immersing themselves in the language to improve their linguistic ability. Therefore, it is important to acknowledge the challenge of linguistic proficiency and be mindful of its impact on the learning environment.

Top tips:

- Ensure resources (e.g. lecture slides, readings, case studies, activity instructions) are provided 48 hours before so students can translate/ familiarise themselves.

- Plan sessions with thinking/quiet time allowing students to process the information.

- Use images and clear straightforward language.

- Write new terms or acronyms and abbreviations on the board or slides and explicitly point them out and explain them.

- Consider your pace and use of metaphors, idioms and culturally specific references, without offering explanations for their meaning.

- Explain UK-specific references to cultural or historical examples or artefacts.

Linguistic proficiency plays a fundamental role in students’ ability to fully integrate into their new context. Below you will find a selection of international students’ perspectives on linguistic considerations from Jenkins and Wingate (2015).

Student 1

IELTS is about giving your opinion, like you have a topic and you write an introduction, a body and a conclusion, and you come up with your ideas and that’s fine. And then you think you should do the same in your university essays.

Student 2

The assignments they gave us were always for evaluation, for marking. But they might give us different types of assignments, just to give feedback.

Student 3

But the problem is the time […] and I don´t look at it [i.e. grammar problems] as something that I really need to improve because I´ve got other priorities, I need to submit coursework, I need to do my assignment, so that problem doesn´t get resolved.

Student 4

If you are disabled they give you some allowances, they give you some empathy, they give you some you know credits [...]. If you are dyslexic they give you some, they give you some exemption as well, right? When you´re a foreign student you almost like a dyslexic person, I mean, not literally the same but you´re almost fulfilling the disabled criteria […] so what I would suggest is if universities look at the point these people are making […] and the ideas and the knowledge that the foreign students have got to impart or put, that should be marked in terms of criteria.

Here you will find guidance to help reduce the linguistic barriers international students face

Lectures

Provide guided questions for pre-session reading (to focus attention on key issues and give purpose to reading.

• List Intended learning outcomes and keep referring back to them to explain why they’re important.

• Use a mix of audio/visual materials and presentations.

• Build in pauses.

• Use images and speak clearly and slowly.

• Use open ended questions to help aid discussion.

• Provide opportunities for peer discussion.

• Provide pre session tasks and readings in advance, so students can prepare for the lecture content

Assessment

Discuss and analyse the rubrics/assessment criteria.

• Allow students to discuss and analyse exemplars (alongside assessment criteria)

• Offer opportunities for formative feedback early on (peer and/or lecturer feedback)

• Don’t assume everyone knows what ‘being critical’ means.

• Explain what marks mean.

• Provide assignment checklists.

• Encourage/ support reflection/ self-assessment (what went well, what can I do to improve next time)

Teamwork

There is much research on the best approach to teamwork within a multicultural setting. The approach you take will depend on your students and the discipline but it should:

- Discuss the benefits of working with others, raising the issue of cultural differences and potential misunderstandings with students before the activity.

- Set ground rules (co-created with students), different roles, expectations, and what success looks like.

- Support groups to come to a common agreement as to how they will handle contentious issues that may arise.

- Assign groups to help promote social cohesiveness between cultures (Burns,V 2013) and avoid students selecting to work in mono-cultural groups

Seminars

- Explain what seminars are for and what you expect from the students.

• Provide pre-seminar preparation tasks.

• Find resources/ examples from students' contexts.

• Tap into students’ expertise and provide opportunities for students to share from their context (but don’t force them).

• Allow for thinking time before expecting an answer and allow students to finish.

• Get students to share their thoughts/ ideas with each other before reporting back to the whole class (creates a safe space to share).

Contentious issues

Focus on an exploratory model of discussion- seeking information to gain a new perspective.

• Anticipate material that could be controversial and actively plan to manage it.

• Model behaviours of responding using neutral statements.

• Be explicit about the value of knowing what you don’t know.

• Use open questions to navigate the discussion.

References

References

Ecochard, S. and Fotheringham, J. (2017). International students’ unique challenges – Why understanding international transitions to Higher Education matters. Journal of Perspectives in Applied Academic Practice, 5:2, 100-108

Héliot, Y., Mittelmeier, J. and Rienties, B. (2020). Developing learning relationships in intercultural and multi-disciplinary environments: a mixed method investigation of management students’ experiences. Studies in Higher Education, 45: 11

Lomer, S. and Mittelmeier, J. (2023). Mapping the research on pedagogies with international students in the UK: a systematic literature review. Teaching in Higher Education, 28:6, 1243-1263,

Lomer, S., Mittelmeier, J. and Carmichael-Murphy, P. (2021). Cash cows or pedagogic partners? Mapping pedagogic practices for and with international students. Society for Research into Higher Education (Research Report). University of Manchester.

Lomer, S. (2017). Recruiting International Students in Higher Education Representations and Rationales in British Policy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

Marlina, R. (2009). ‘I Don’t Talk or I Decide Not to Talk? Is It My Culture?’- International students’ experiences of tutorial participation. International Journal of Educational Research 48:4, 235–44.

Newsome, L. and Cooper, P. (2016). International students’ cultural and social experiences in a British university: “Such a hard life [it] is here”. Journal of International Students, 6:1, 195-215

Rhoden, M. (2019). Internationalisation and intercultural engagement in UK Higher Education – Revisiting a contested terrain. In International Research and Researchers Network Event. Society for Research in Higher Education.

Scudamore, R. (2013) Engaging home and international students: A guide for new lecturers. The Higher Education Academy.

Straker, J. (2016) International student participation in Higher Education: Changing the focus from “International Students” to “Participation”. Journal of Studies in International Education, 20(4), 299-318.

Where next?

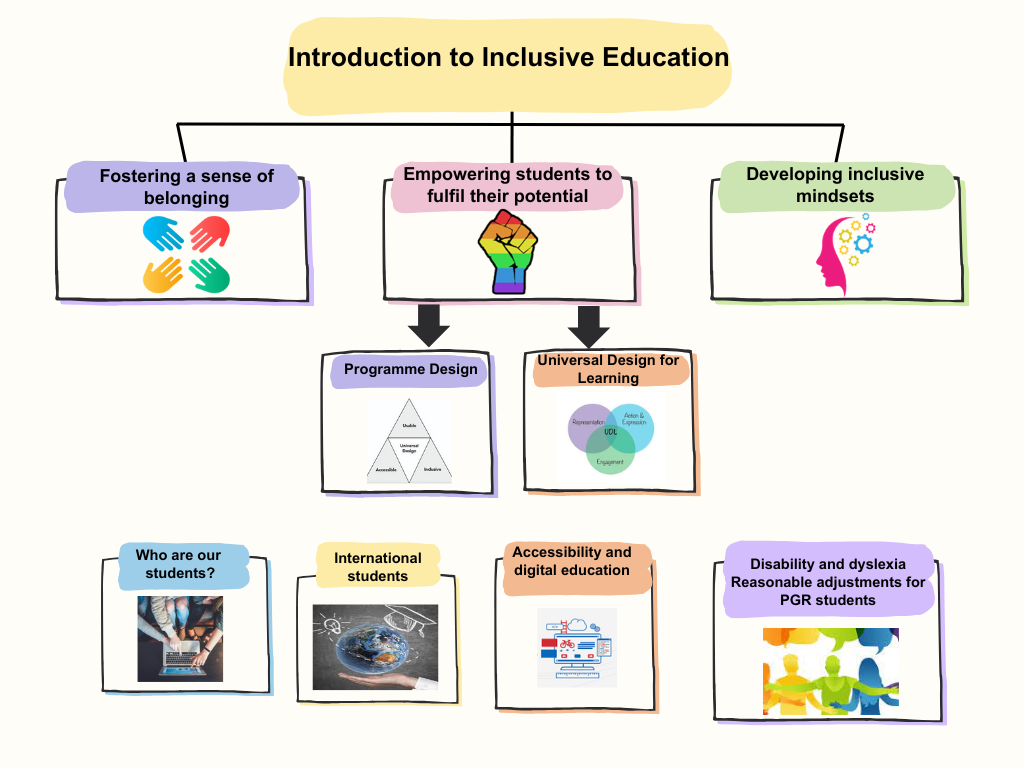

Map of Topics

Below is a map of the toolkit and workshop topics, to aid your navigation. These will be developed and added to in future iterations of this toolkit:

You’re on page 9 of 9 Inclusivity theme pages. Explore the others here:

1.Inclusivity and the CU Inclusive Education Framework

2.Introduction to Inclusive Education

3.Fostering a sense of belonging for all students

4.Empowering students to fulfil their potential

5.Developing inclusive mindsets

6.Universal Design for Learning