Developing Inclusive Mindsets

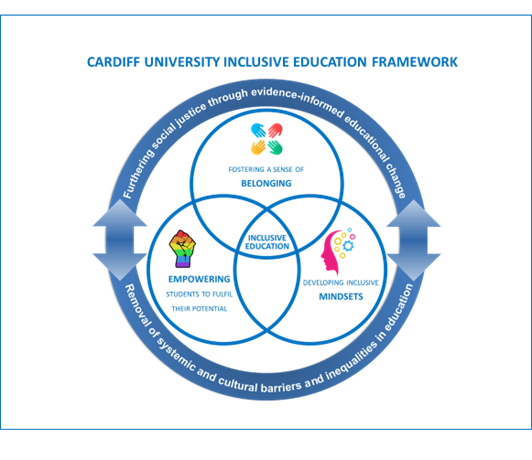

The Cardiff University Inclusive Education Framework

We have developed a university-wide framework for facilitating and supporting schools and departments to embed inclusive education within our educational provision. Inclusive Education links to both the wellbeing of our students, and student satisfaction and experience, and it sits with the ‘creating an inclusive learning community’ priority. You can read more on the Framework on the Inclusivity and the CU Inclusive education page.

Developing Inclusive Mindsets

Developing Inclusive Mindsets

Developing inclusive mindsets is one of the three dimensions of the framework, which looks to overcome challenges to belonging and achievement through “addressing wider concerns about facilitating social justice and bringing about equity” (Stentiford and Koutsouris 2020), and to support students to become active agents in the development of inclusion.

Our areas of focus:

• Drawing on the diversity of the community to enrich the learning experience

• Articulating inequalities and privilege including critiquing understandings of the origins of subject knowledge

• Inspiring students to become champions of inclusivity, equipping them with the skills to foster and support inclusive environments

The following sections will explore each area of focus, providing an overview of key literature, reflections and top tips. The deeper dive section (below) provides case studies and resources to support practice. To get you started, here are top tips on how to support students in developing inclusive skills:

Higher education is more diverse than ever before, and therefore institutions play a key role in equipping students with the skills needed to become inclusion champions for their future. The diverse learning environment can provide a space to discuss, reflect and critique the concepts, ideologies and histories of disciplines and pedagogies. It can also enable students to draw on their own cultural experiences, and foster cultural awareness of the world around them. When we approach our teaching from an inclusive perspective, valuing the diversity of our students and reflecting on our own assumptions and bias, we place the needs of our students at the centre of the learning. (Herrez, N.J., McBrien, E.B., Scott, C. 2023).

When students work collaboratively, bringing different perspectives, thoughts and beliefs, feeling safe to be their authentic selves in learning spaces, they can become active agents in their own development, in enacting inclusion and actively move towards social justice. It is important to acknowledge that students will have varying levels of understanding of EDI and inclusion topics. Therefore, the opportunity to discuss and critically reflect on equality, diversity, and inclusion themes within the curriculum is an important aspect of the student experience. So, how do we ensure we are creating opportunities in our practice to inspire students to become champions of inclusivity, equipping them with the skills to foster and support inclusive environments?

1. Drawing on the diversity of the community to enrich the learning experience

A central idea of the African philosophy Ubuntu is the recognition of the interconnectedness of human beings, while acknowledging the inherent worth of every individual. It suggests that all persons have something to offer, and not one form of expertise should prevail over the other. The source of knowledge is, therefore, the community, not the individual. Inclusive pedagogical practices provide opportunities for students to reflect and draw on their own lived experiences, enabling everyone to learn from each other. This can increase both collaboration and innovation. Cultural diversity can have practical benefits in learning spaces if we reflect on it from a culturally sensitive perspective (Attila Dobos 2024). It can enhance the quality of discussions and lead to a deeper understanding between students.

Developing cultural competence within the curriculum fosters the value of respect, and appreciating and understanding different cultural backgrounds, thus enabling all to work effectively in our increasingly globalised world. The Advance HE Report, Creating Digitally Inclusive Strategies (2023), for example, highlights the importance of designing learning environments that not just foster academic growth but to support the cultural and social growth of all learners.

The Intercultural curriculum (Advance HE 2019) creates a safe space for learners to cohabit, where different perspectives are acknowledged, welcomed, and learned from. Giving space for students to discuss, question and critique in a safe and nurturing environment enables students, regardless of any barriers they might experience, in order to feel valued and have their voice heard.

Here you will find practical considerations when reflecting on how to draw on the diversity of your student community:

Understanding data

Do you use data to understand the diverse characteristics of students on your module or programme? Student data is valuable in giving you a clear picture of who your students are, and the diverse groups of students you are teaching.

Get to know your students

You can’t draw on the diversity of your students if you don’t know what that diversity is. Spend time getting to know each other. This could be achieved during pre-session tasks, induction or the first few weeks of teaching. A nice example is asking students to bring a picture/ or piece of music that makes them think of home. This could be uploaded and a collage made in the first week, showing different cultures, places and backgrounds.

Create safe spaces

Students need to celebrate and respect their own diverse backgrounds and those of each other. Provide space within sessions for students to learn, value and reflect on each other's cultures and backgrounds. As students learn about their diverse backgrounds and perspectives, take the time to highlight what is offensive and the distinction between cultural celebration and appropriation.

Cultural sensitivity

During sessions ensure there are clear behavioural expectations agreed by all students around diversity and inclusion discussions and behaviours. It is important to have open dialogue amongst students, however it is equally important to ensure all students are sensitive to each other’s culture, beliefs, language acquisition, and backgrounds. Take the time at the beginning of a module or programme to co-design with students how you will value each other's intersectional identities and deal with contentious issues. In the deeper dive section, below, look at top tips when dealing with contentious issues.

Provide freedom and flexibility

The most valuable lessons are often learned through a student’s own experiences, so providing opportunities for students to draw on their own experiences in the module or programme encourages connection with the discipline and curriculum. Allow students to read and present materials that relate to the fundamental lesson. This allows students to approach the topic from their perspective and shows that who they are is valued, in relation to the discipline. Peer work and opportunities to work in diverse groups allow students to hear different perspectives and help prepare them for the global workforce.

Here you find student perspectives and examples of good practice:

Celebrate each other

‘I appreciate the School of Bioscience cultural event and how it celebrates various cultures and highlights diversity’

‘Psychology has events and talks related to a variety of topics- e.g., an event for world down syndrome day. I believe it is really beneficial to create awareness.’

‘I enjoyed the St Davids celebration SOCSI hosted by Sion. I enjoyed singing the Welsh national anthem and as an English person, I really enjoyed learning about Welsh culture.’

Safe spaces to share

‘I believe that my lecturers were very encouraging in terms of allowing students to bring their own perspectives and thoughts into the sessions. Almost all of the lecturers I encountered during both my UG and PGT studies were keen to hear students' perspectives on what they wanted from the sessions, as well as how lecturers could facilitate those wants.’

‘Opportunities to engage with international students expanded my worldview.’

‘Be mindful of differing backgrounds and approaches to EDI topics. Not everyone will have exactly the same background, nor will they have the same perspectives when discussing EDI topics. If a student seems unable to relate to the EDI topics that are being discussed, consider adapting the discussion accordingly. Also, never force a student to disclose anything about their background if they do not wish to do so. Make sure that students are comfortable, and that they discuss such matters on their terms.’

‘Encourage discussion between students about their experiences, perhaps in small groups, to encourage the development of a safe space. As per the previous point, never force a student to disclose anything that they do not feel comfortable saying. If it helps, leave the room briefly while students engage in small-group conversations to emphasise that the learning is very much directed at them and their needs.’

2. Articulating inequalities and privilege including critiquing understandings of the origins of subject knowledge

Within the sector there has been an increasing emphasis on the importance of diversifying, decolonising and implementing an anti-racist curriculum and challenging our unconscious biases in the way we design and deliver teaching.

Below we discuss how these perspectives and approaches can help us reflect on and improve our practice. However, it is worth noting that although we discuss them separately, there are also similarities and overlaps between the approaches.

Diversifying and Decolonising the curriculum and critiquing understandings of the origins of subject knowledge

Much literature has been written on diversifying and decolonising the curriculum with many perspectives on what each term means.

At Cardiff University we acknowledge these differing viewpoints and value the varying perspectives. The following section draws holistically on the literature of both diversifying and decolonising pedagogies, appreciating the interwoven principles that acknowledge the need to diversify, identify, critique and dismantle existing origins of knowledge from an ethnocentric perspective.

“Decolonising the curriculum interrogates the ongoing impact of legacies of colonisation and imperialism on knowledge production. A decolonial approach concerns itself with deconstructing existing hierarchies, in favour of drawing on multiple knowledge systems/ways of knowing in order to integrate a range of perspectives, with a particular focus on amplifying the voices currently underrepresented in the curriculum” (UAL 2023: 3).

Disciplines that are part of the academy have not been immune to the process of colonisation. How we gain an understanding of the world is grounded in cultural world views that have either ignored or been antagonistic to knowledge systems that sit outside those of the colonisers. Our research and teaching methodologies, all instruments of knowledge production, are also used as ways to classify, organise and represent knowledge.

Some have expressed concern that decolonising the curriculum is about dismissing or deleting what has been: But decolonising is not about deleting knowledge or histories that have been developed in the West or colonial nations; rather it is to situate the histories and knowledges that do not originate from the West in the context of imperialism, colonialism and power, and to consider why these have been marginalised and decentred (Arshad 2021). Paying attention to representation and decolonising the curriculum is a major focus in many Higher Education institutions.

There is great guidance from University of Arts London which can aid your reflections on this significant issue in inclusive education.

SOAS have produced a helpful toolkit, watch the video below from SOAS, and read the Case Study (OU 2018), or read more about De Montford’s project on decolonising the curriculum.

Arshad (2021) suggests a number of stages when approaching decolonising:

-

- Develop understanding of why decolonising the curriculum is important

- Examine our own subject discipline to identify if there are alternative canons of knowledge which have been marginalised or dismissed as a result of colonialism

- Ensure a range of voices and perspectives are represented and ways you might re-conceptualise the curriculum to reflect wider global and historical perspectives.

- Consider the diversity of our student groups and ensure learning content moves beyond Western to global frameworks.

- Diversifying the reading list has been one route that many have chosen as a quick way to begin the journey of decolonising the curriculum. There is subliminal value in diversifying the reading list, because it is a way of acclimatising learners to the presence of a range of writers, be that writers from diverse ethnic groups, writers who identity as LGBTQ or other characteristics.

- From diversifying to decolonising: provide opportunities for the students to discuss the historical legacy of colonisation for that subject area. For example, in astronomy when we discuss life, universe, planet and stars, we can open up discussions on how different perspectives might understand these topics. How might different indigenous communities understand and talk about stars? Would it be in the language of exploration and conquest of space or in terms of navigation and survival? (Arshad 2021)

Anti racism pedagogy

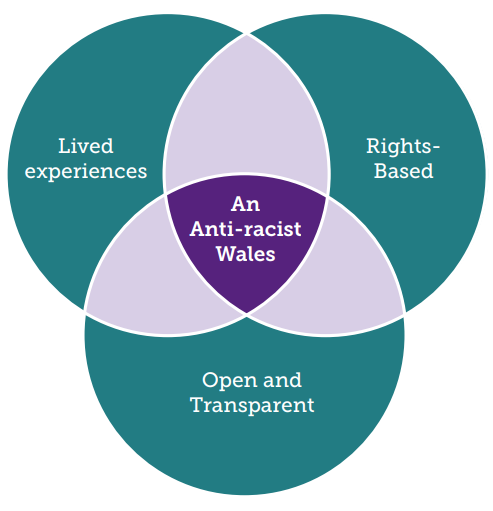

figure1: Anti-racist Wales Action Plan: 2022 | GOV.WALES

There has been acknowledgement of institutional and systematic racism within society since the death of George Lloyd Floyd in 2020 and the Black Lives Matters movement, which ignited a call to action for society as a whole to become actively anti-racist.

Welsh government has pledged to an anti-racist society in Wales by 2030 with a key action for HE of ensuring the experience of all students is equitable, and that racial discrimination and institutional racism is addressed and dismantled. In 2020, Advance HE launched the Tackling Structural Race Inequality in Higher Education campaign. Its purpose was to support UK Higher Education institutions to better ‘understand and address … structural race inequalit[ies] in all aspects of higher education.’

Cardiff University (‘Our future, together’ strategy, 2024) is committed to becoming an actively anti-racist institution by 2030, with much work already underway both across the institution and in engaging with communities across Wales and the sector.

What is an anti-racist curriculum?

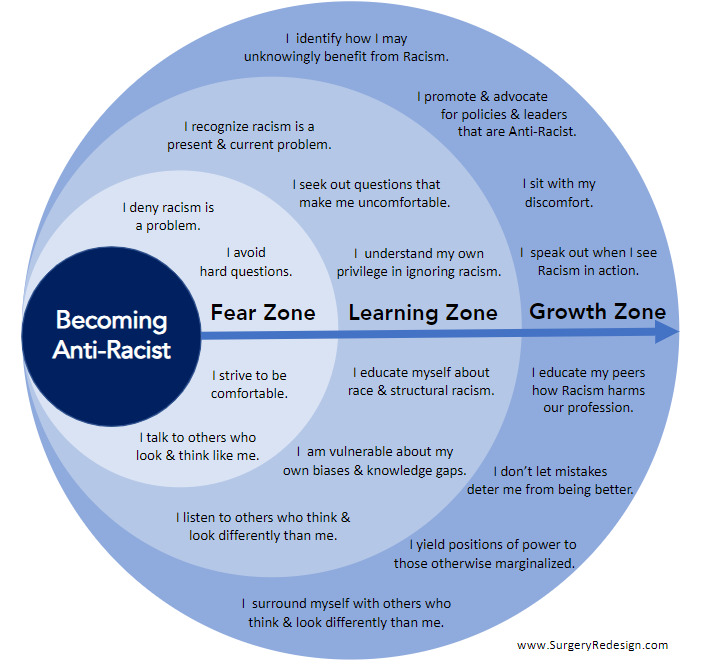

Where decolonising and diversifying the curriculum focus on the need to critically reflect, diversify, question and deconstruct existing hierarchal knowledge systems, anti-racist pedagogy begins with oneself and the importance of reflecting on our own pedagogies, behaviours and beliefs.

When considering what this means for learning and teaching, anti-racist practice focusses on examining our own practices, pedagogies, curriculum and behaviours in order to acknowledge biases and actively implement change. The process of self-reflection is key to anti-racist practice and moves away from simply incorporating racial content in modules and programmes that have a race or ethnicity focus, towards unpicking pedagogies used to teach and research, questioning our own position within the learning environment. (Kendi 2019).When we reflect on our own assumptions and bias and actively engage in antiracism pedagogy, we impact how we design, teach and assess our students with the goal of providing a curriculum that enables all students to engage and grow in their own antiracism journey.

“The only way to undo racism is to consistently identify it and describe it–and then dismantle it.” –Dr. Ibram X. Kendi, How to Be an Antiracist (2019)

Drawing on the work of Kendi (2019), because racism is institutional and systematic, being an anti-racist is an active process of identifying and opposing racism in order to actively change the polices, practice and behaviours and beliefs that perpetuate racist actions. Inclusion is the foundation of good learning and teaching practice but when you view learning from an anti-racist lens you build on best practice and critically examine the who, why and how we are teaching.

Anti-racism pedagogy is constantly evolving, with resources available across the sector that provide guidance on how to develop practice across different disciplines. The Anti-Racist Curriculum Project by Advance HE (2021) Anti-Racist Curriculum Project | Advance HE provides a wealth of guidance on different aspects of an anti-racist curriculum. If you wish to explore more toolkits and guidance from across the sector jump to the Deeper Dive section, below.

When situating your discipline and curriculum using an anti-racist perspective, a key consideration is the need to create safe and brave spaces for staff and students to bring their authentic selves and share their experiences and perspectives. Both will have varied understanding of anti-racism pedagogy, and it is important to acknowledge this and provide opportunities for all members of the learning community to learn and reflect. Below you will find considerations when implementing anti-racism into the curriculum.

Creating brave spaces

Based on the work of Arao, B, & Clemens, K (2013):

- To what extent are teachers and students aware of what might constitute racist or racialising behaviour in a learning context?

These might include manifestations of personal disrespect, such as cutting students off, laughing at them or speaking over them; expecting someone to act as a ‘spokesperson’ for a particular group or view; the stigmatisation of different pathways into education or linguistic skills which may be associated with ethnicity; unconscious forms of bias in terms of recognition, expectations and personal interactions; as well as more obvious forms of discrimination and bias.

- Is there an understanding of how these can be addressed?

- Is space and time given in modules, lectures, seminars and office hours for students to openly acknowledged and confront this?

- Do students have a place to go to discuss these matters?

Learning and teaching practice

- Anticipate how to frame topics related to race and various forms of inequality, as they may be emotionally salient in different ways for students with a range of experiences.

- You might add an anti-racist statement to your syllabus that is authentic to your voice and discuss its implications for your course with your students.

- Consider pausing to reflect and consider if there have been times when you could have been more intentionally or explicitly anti-racist while leading a discussion or class session. To build on this reflection, try regularly gathering feedback from your students to understand their experiences and perspectives.

- Try providing opportunities for students to reflect on their own biases, for example through individual written reflection or small group discussion. Students may have a range of emotional responses, which may mean planning space for them to process those emotions.

- If you’re comfortable doing so, share your own journey with your students as a learner who makes mistakes but continually strives to do better. Like your students, you may need time to process your emotions based on your positionality and experiences.

Language matters

From Advance HE Anti- Racism Curriculum Project

ARC Language Matters Portfolio March 22.pdf

Arbu-Arqoub and Alserhan (2019) suggest the following thoughts and actions to try and overcome misrepresentation.

Unconscious Bias and ‘Epistemic Credibility’

Watch this short introduction to unconscious bias:

Often, educators seek or claim to pursue neutrality and fairness in their teaching. Regardless of good intentions, by pursuing neutrality, educators may be complicit in ignoring existing power dynamics and maintaining inequitable systems. An educator’s assessments of who can learn and who can produce knowledge are influenced by their assumptions about the students, based on their decision to take into account or exclude aspects of their social identities.

In the learning environment, epistemic credibility (or knowledge credibility) is the authority given to a learner to receive and produce knowledge. In other words, epistemic credibility is the authority to be a learner as well as a to be a contributing member in the learning and teaching process (Parsons and Ozaki 2020).

Simply put, educators grant or deny epistemic credibility to their students. They do this consciously or unconsciously, as they gauge a student’s knowledge authority (i.e., how much do/can/should they learn, how much do/can/should they contribute in class). Often, when lacking knowledge about a person, educators may resort to judgments of appearance (for example, the appearance of belonging to affinity groups), even if they are unaware of it. Educators often make these judgments based on what they see, know, or assume about their learners, based on appearance or interactions with them. Being aware of student identities and educators’ epistemic beliefs is fundamental to creating inclusive classrooms (Parsons and Ozaki 2020).

3: Inspiring students to become champions of inclusivity, equipping them with the skills to foster and support inclusive environments

We all have a role to play in creating and sustaining a respectful, diverse and inclusive university community, thus engaging in inclusivity topics, discussions and wider global issues are fundamental in an inclusive learning environment. However, research suggests that academic departments rarely discuss inclusivity, unless it is a focus of the discipline (Perez et al. 2020). Without specific training or induction in EDI, and ongoing sustained conversation on the implications of EDI, students with minoritised identities can feel marginalised and tokenised, if not overtly targeted, based on their identities.

Cardiff University is committed to embedding EDI practices across the institution. An example is the ‘EDI for Students’ module, which all academic staff have access to, and all incoming students are timetabled to complete in the first few weeks of their university experience. There are two iterations, for undergraduate and post-graduate students. See the trailer here:

To complete EDIAware, log onto Learning Central and in ‘Organisations’ locate the undergraduate module EDIAware-ORG-UG (English medium) orEDIAware-ORG-UG-Cymraeg (Welsh medium Alternatively access the postgraduate taught module EDIAware-ORG-UG-PGT (English medium) or EDIAware-ORG-UG-PGT-Cymraeg (Welsh medium). If you need access, contact the Digital Education team for access.

The EDI module provides a starting point for a student’s awareness of EDI principles. However, there is a need for academic departments to consistently provide intentional opportunities for individuals to learn about EDI within their disciplines and fields. if we are to create inclusive learning environments and prepare students to contribute to a complex and interdependent global society’ (Parsons et al. 2020: 133).

Providing development and training in EDI isn’t just about ensuring our University provides an inclusive environment in which to learn, it is also about providing students with the vital skills needed to be inclusive leaders of the future. An important aspect of student experience is the broader educational gain students achieve from higher education. As a sector we are anecdotally driven by data however when focussed on the educational gain university brings that is not so easily measured. It is the richness of the wider experience and skills of communication, working with diverse groups, handling difficult conversations, and leaning into the uncomfortable that equip students to become inclusive leaders.

Here you will find 2 considerations from the student perspective:

Encouraging respectful debate on difficult topics helped broaden my understanding.

‘Providing regular opportunities to discuss EDI topics in a safe and respectful space. In practice, this can be challenging to manage, but when done thoughtfully, it builds trust and mutual respect. I’ve seen how open, facilitated conversations can shift classroom dynamics in a really positive way.’

Providing content warnings for sensitive topics helped me feel prepared.

‘It might be worth emphasising to students at the start of lectures and seminars that they are welcome to step outside or remove themselves from the conversation in other ways if it distresses or unsettles them. They should also have the option to suggest changing the topic.’

There are a number of ways we can embed equality, diversity and inclusion into the curricula, our practices, the materials and activities used to support learning, and the classroom cultures fostered by student-staff interactions (Advance HE 2018). There are also a range of useful tools to help you embed EDI in your teaching. Try this ‘Brave Spaces’ activity with students.

As previously discussed, we don’t just have a duty as a university to impart knowledge of our discipline but to guide and equip students with the necessarily skills for their futures not just professionally but also as citizens over an everchanging globalised world. Our graduate attributes at Cardiff University provide focus on key skills that are recognised as inseparable from everyday interactions, relationships, teams and organisations regardless of the sector or career. However it is important to acknowledge that Equality, diversity, and inclusion values are increasingly embedded in the workplace.

Graduate Attributes at Cardiff University

To find out more about our work on employability, read our Employability pages in the Toolkit.

When thinking about developing effective inclusive leaders, we need to focus on the behaviours and traits that they need to exhibit. Therefore, the more we support students to practise these behaviours and expose them to positive situations in our environment, the more we can refine and cultivate behaviours we would like them to embrace. When we consider our curriculum we therefore need to reflect on how we provide opportunities for students to practice and improve these skills in an environment that is safe for all students.

Recording of the page

Deeper Dive section

Empathetic Pedagogies

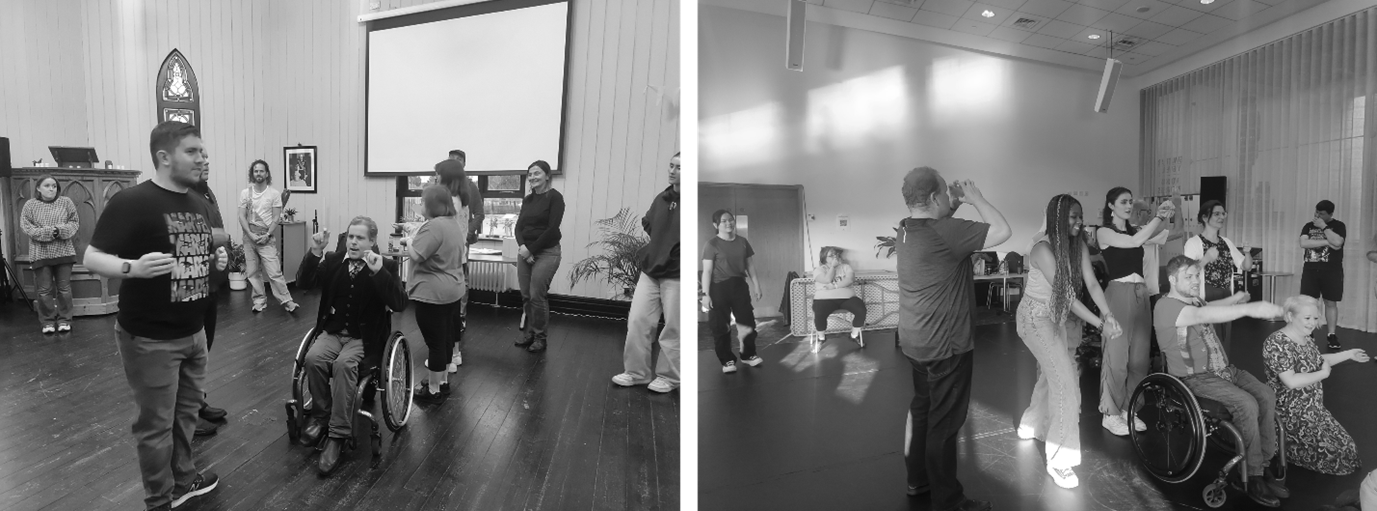

Empathetic Pedagogies: Using performing arts, ethnographic means and participatory design to develop inclusive mindsets.

Project Summary

The Empathetic Pedagogies project was an Education Innovation Funded project by Cardiff University’s Teaching and Learning Academy within the theme of ‘Developing Inclusive Mindsets’.

Accessibility in building design is commonly pursued and interpreted as compliance with building regulations and primarily focuses on physical disabilities. The needs of users with visible and invisible disabilities are often overlooked. Particularly in performing arts spaces, inclusive design is often an afterthought for the design process.

In this project, we invited students to explore first-hand the needs of performers with physical and/or learning disabilities through their participation in performing arts games and experimentation. They worked on a live-brief, engaged with an inclusive drama group and proposed stage designs for a script that access and inclusion were creative tools and instigators of stage action.

The project advocated for the integration of performing learning strategies in design education as means of achieving an empathetic understanding of design stakeholders but also as a pedagogic vehicle for creating inclusive mindsets in design education and beyond.

The project built on previous and currently developing research of the 2 key applicants on creativity as a form of alterity in design learning (Ntzani 2020, Ntzani & Banteli 2023) and expands from Amalia Banteli’s pedagogical experimentation during the 2020 Welsh School of Architecture Vertical Studio unit: Access and Inclusion.

Outcomes and Impact

Both the Empathetic Pedagogies project as well as the Access and Inclusion Vertical Studio has shown that creating empathetic bonds between students and members of disabled communities makes students critically reflect on inclusivity as a value within their discipline. Architecture students that participated in the project found that their design ethos expanded beyond architectural purpose and aesthetics to space-making and communication formats that are inclusive of all. The live project collaboration and creative tools exchange cancelled patronising approaches to participatory design and public engagement and allowed all involved members to contribute confidently to different parts of the project.

Video: Student reflections on the Empathetic Pedagogies project

Interestingly, inclusivity considerations of students expanded beyond the disabilities of the drama group they interacted with to include other disabilities that they had not experienced as well as cultural and language considerations. This was manifested through adding Welsh translations to text used in their suggested stage sets and the addition of braille on objects they created as part of their stage set design.

Empathetic bonds did not build by merely bringing in contact the two groups (the students and the drama group) but through mutual creative exchanges between the two groups. Students joined the performers in warm-up exercises and rehearsal routines whereas performers participated in design and sketching exercises. These ‘slip into my shoes’ practices aimed to foster understanding among all creative individuals and facilitated knowledge exchange and sharing of the challenges of creative beginnings. These practices created an empathetic bond reminding all participants of the strange and uncomfortable nature of creative encounters.

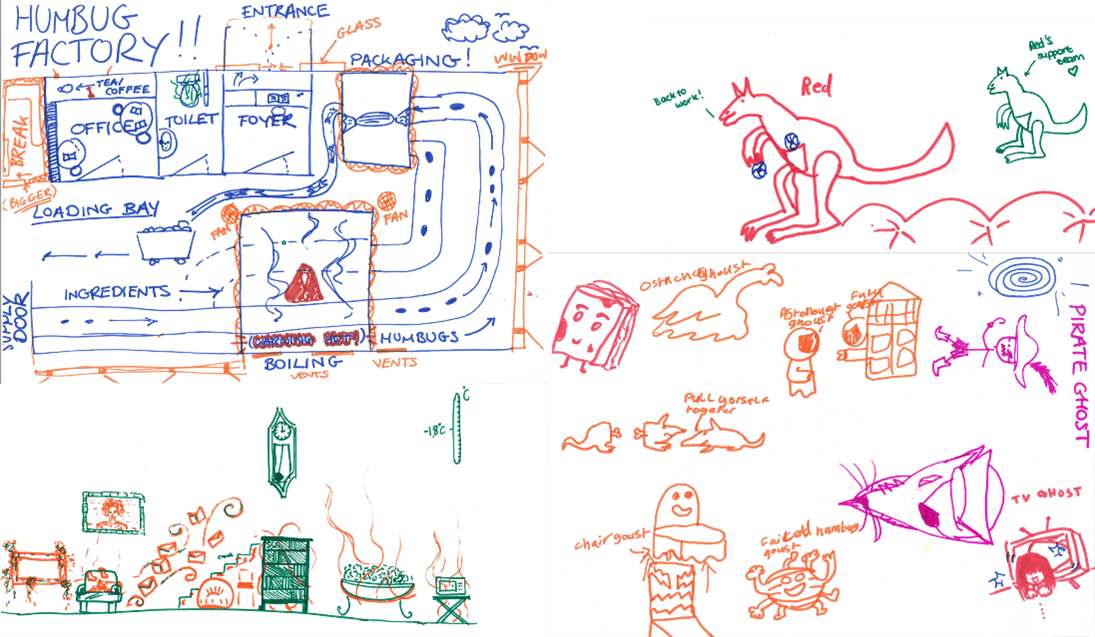

Building Empathy through participatory design: Sketching exercises where students and Hijinx Odyssey members explored factory settings, different ghost identities and comfort spaces for factory workers to take their break.

Building Empathy through participatory design: Sketching exercises where students and Hijinx Odyssey members explored factory settings, different ghost identities and comfort spaces for factory workers to take their break.

Building Empathy through theatrical improvisation: Improvisation exercises with Hijinx Odyssey exploring factory settings.

Video: Building Empathy through theatrical improvisations with Hijinx Odyssey

Building Empathy through participatory design: Students presenting their initial stage set design ideas to Hijinx Odyssey members to get their feedback.

Challenges

Managing Student Engagement and Timing of project activities

The main challenge we faced during the project was student engagement and timing the activities around the students’ academic workload. The project did not form part of the curriculum; student participation was optional and there was no assessment associated to the project. As such, timing of the project activities needed to be carefully planned to avoid busy periods for students.

The Importance of Flexibility in Live-Brief Projects with External Partners

Working on a live-brief and with external partners gave very valuable lessons to students but required flexibility in adapting project requirements as the project unfolded. This is something that needs to be stressed as part of the learning process when working on a live-brief and with external partners, so that the students know that this can become a challenge that will however expand their learning through the project.

Main conclusions and Next steps

Though the immediate benefits to architecture as a creative/ design-based course are apparent, we see transferable and scalable benefits to other courses with similar elements of practice. As the project expands to investigate performance and creative pedagogical vehicles as means to empathetic and inclusive design, its outputs may benefit courses across the university that wish to implement a more creative, innovative and inclusive learning experience for students.

The mutual participation and knowledge exchange between students and non-academic stakeholders through creative activities can provide a very fulfilling and engaging learning experience for all parties. It can infiltrate the way we share and debate values with our students and create a step-change in the way we can foster inclusive mindsets for education and practice.

The Empathetic Pedagogies project is already planting seeds in our Programme Redesign, with student allies proposing that Equality Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) values are explicitly stated in the Learning Objectives of our new modules. It triggers a conversation on the civic and social obligations of higher education and accredited professions. It has also given life to a young team of researchers working on research grants and funding applications that aim to spread EDI values outside the safe boundaries of design education and in its realm of practice.

Tops tips

- Working with clear pedagogical values and tools

A key thing is not to work with learning objectives in mind, but with pedagogical values and principles when you choose or design a similar project or activity. This can help you work or invent a project that brings insights and bears value beyond your disciplinary boundaries.

At the same time, it is important that those values and principles are focused and clear, rather than generic and broad. It’s a tricky balance but often the selection of tools makes things precise. For example, for us, it was EDI values and performing pedagogies as a tool to distill them in design.

- Designing Inclusive Case Studies for Diverse Project Members

Case-studies need to be inclusive of staff and students with varying academic aspirations and career needs. This requires careful development of the brief and project scheduling to ensure that all members of the project understand and can engage with the project in their best capacity.

- Engaging External Communities to Enhance Project Impact and Empathy Building

Consider the external communities that relate to the project values. You need to define if the project relates to different audiences and if not, you need to consider who you wish to benefit and positively impact. Involving these affected communities in the project greatly increases the project impact and enables the building of empathetic bonds between these communities and the students.

- Embracing Learning Through Unintended Outcomes

Remember that such projects/ activities are a learning vehicle for all, even when anticipated outcomes are not the desired ones. This was certainly the case for us when we saw our students design ambition stepping down to create space for ethics and politics of participation.

- Creating a Safe and Open Environment

Make sure the space and time of your project/ activity is a safe one for all involved; to express views, interrupt the process and negotiate the targets – particularly when working with a live-brief and external partners. This presupposes learning relationships based on directness and honesty. If we knew well what we work on, we would not have to experiment on it.

Principal Investigator: Amalia Banteli, Lecturer in ARCHI

Project co-lead: Dimitra Ntzani, Senior Lecturer in ARCHI

Project collaborator: Ed Green, Senior Lecturer in ARCHI

Interprofessional Student Leadership Academy (ISLA) programme

ISLA Project -Interprofessional Student Leadership Academy programme

Project Summary

What was the project about?

Evaluating the effectiveness of an Interprofessional Student Leadership Academy (ISLA) programme was an Education Innovation Funded project by Cardiff University’s Teaching and Learning Academy within the theme of ‘Developing Inclusive Mindsets’. The School of Healthcare Sciences in collaboration with the School of Dentistry has developed an interprofessional leadership academy for students across undergraduate healthcare programmes and dentistry. The aim is to provide inclusive extracurricular opportunities for students to develop as future leaders of health and social care and be confident in demonstrating the principles of compassionate leadership. The programme was developed in collaboration with clinical partners, students, patient and service users and academics and was led by Professor Teena Clouston and Dr Alison H. James, Reader in Healthcare leadership.

The project began in October 2023 and was completed in July 2024 in the pilot year of the programme. At the beginning of the ISLA programme, 7 students had applied and accepted onto the programme and 5 students completed. Students were asked to complete feedback questionnaires at the beginning, middle and end of the programme, so while 7 were completed initially, the end and middle questionnaires were completed by 5 students. All feedback was submitted anonymously and collated by the employed evaluation assistant, Anaxia Uthaya Kumar, employed through the student job shop.

The aim of the evaluation project was to capture data to ensure the programme is an effective learning experience for students, enabling and supporting their inclusive leadership development. Guest speakers, Action Learning Sets, individual coaching was provided, as well as creative methods for reflection and learning strategies from October 2023 to June 2024. Coaching was arranged by the individual student and their coach, while other sessions were delivered on campus over 4 half days and a final presentation of projects afternoon. The objectives were to capture feedback from students at different points of the programme, collate and review the data, disseminate through conference presentation and case study to the University and wider and apply learning through review of the programme content, delivery and structure for future cohorts. The desired outcomes set at the inception of the programme were that students would develop and demonstrate:

Increased awareness of resources and opportunities to develop self-awareness, self-agency and individual leadership qualities.

Increased awareness of personal goals for leadership development

Higher self-awareness and emotional/social intelligence

Higher appreciation of the effectiveness of interprofessional and collaborative working

Increased confidence in applying compassionate and values-based leadership approaches in practice

The thread that runs throughout the desired outcomes is the development of inclusive and compassionate leadership skills that will equip students in their future careers when working in diverse social, economic and cultural patient communities.

Outcomes and impact

What was the impact?

What did you see happen to student engagement, outcomes, attainment or evaluation. What worked well and what worked less well?

The programme began in October 2023 and was completed in July 2024. Using New World Kirkpatrick’s model (2021) , an internationally recognised tool for evaluating and analysing the results of educational, programs four levels of evaluation were considered: Reaction, Learning, Behaviour, and Results. Applying the approach of Bowen (2017), the programme was developed using the ‘Backward design’.

Feedback was collected at the beginning, middle and end of the programme. 7 students completed the first questionnaire however only 5 completed the middle and end questionnaire. All feedback was submitted anonymously, and questionnaires were designed to capture feedback in two areas.

Firstly, students were asked to comment on the relevance and engagement of content and delivery of the sessions and this data will be used to review the programme for the next cohort. All session content was positively reviewed, however, students made helpful comments on the length and delivery of some sessions, and this will be responded to in future programme design.

Secondly, students were asked to feedback on their confidence, learning and development in leadership through the programme.

From feedback captured at the midpoint, all students described a transformation in their perspectives on their personal leadership throughout the program reporting personal growth and an increase in confidence. This was often attributed to the program's emphasis on self-belief and the realization that leadership occurs at all levels of an organisation, rather than a hierarchical position. Students reported relating to leadership as an accessible skill and concept, rather than something distant, unachievable or reserved for select individuals.

Overall, all students who completed reported the programme reported a positive learning and development experience. The evaluation project has provided valuable feedback from students on their experience, learning and impact going forward as healthcare students and future professionals. The data has also allowed us to respond to student suggestions for future programmes.

The project has provided valuable data demonstrating the learning experiences of students on the pilot year of the ISLA programme and the data establishes it as a valuable learning experience for students.

Feedback from students:

“The program has rendered the concept of 'being a leader' much more approachable and relatable, emphasising the human aspect. Through this, I've gained insights into various leadership behaviours and the challenges inherent in leadership roles. Consequently, I now feel more assured about my potential contributions, both in theory and practice.’

“Engaging in the ISLA project significantly bolstered my confidence in conceptualising and nurturing impactful ideas.”

‘The ISLA project has been a fantastic opportunity to spend time on self-development, explore new ideas amongst like-minded people and hear from some really inspirational speakers across healthcare! I have really enjoyed making personal and professional connections with students and staff from different disciplines that I know will provide an amazing support network as we start our future careers.’

Challenges

Overall, the project was successfully achieved within the timeframe. Areas of limitation included the non-completion of 2 students which reduced our sample to 5 students, and the retirement of a staff member, reducing the amount of time for completion and dissemination. However, the project has been completed, abstracts submitted for dissemination and plans to submit for publication by the end of 2024.

Main conclusions and Next steps

The project findings are easily transferable across disciplines as the project is designed on theory and evidence and acknowledged educational methodologies such as experiential learning and reflection. While the theoretical background to the development of ISLA is based on current evidence on leadership development, the importance of this within the healthcare workforce, and regulatory requirements for healthcare professionals (James 2021, James et al 2022, West et al 2022). Building on the research of Clouston (2017) and James (2021), it acknowledges students’ experiences of leadership, and the resulting emotional reasoning can shape how individuals view their own leadership development and focuses on reflection and conceptualisation. Coaching and Action Learning Sets (Revens 1980) support students and address the following areas which were found to be influential (James 2021):

Expectations and defining characteristics of leadership

Professional values and challenges of leading within healthcare cultures

Self-awareness, emotional intelligence and reflexivity

Bringing contexts of learning together, clinical and theoretical

Role models and representing leadership

Cultural and social contexts of organisations

To make learning experience meaningful and emergent, reflection is encouraged to intellectualise and create learning with conceptualisation and analysis of cultural and social conditions to nurture meaningful learning (Clouston 2018, 2017). The importance of experience and experiential learning is significant as it impacts students’ perceptions of their self as leaders of patient care. Creating time for evaluating and reflecting on experience can support students to further develop their approach and personal development (Dewey 1989, James et al 2022).

Developing the Leadership Academy has been a valuable addition to student experience and undertaking the evaluation has allowed us to take student feedback forward to improving the Academy for future students. The 24/25 cohort has begun and suggested changes have been implemented. Outputs include international presentations of the evaluation, and students who have completed the programme have presented projects at conference. Ongoing evaluations will be completed to continue to improve this experience for students in the future.

Resources from across the sector

A range of resources from across the sector that provide guidance on diversifying, decolonising and anti-racist pedagogy.

Advance HE anti racist toolkit Anti-Racist Curriculum Project | Advance HE

SOAS Microsoft Word - Decolonising SOAS - Learning and Teaching Toolkit May 2018-1.docx

Univeristy of York: anti-racism-toolkit.pdf,

Leeds Beckett: the-anti-racism-toolkit.docx

Anti-Racist Toolkit from the University of Brighton also has a wealth of resources and information: University of Brighton Anti-Racist Toolkit (padlet.org)

Where Next?

The Inclusive Education CPD Offer

Toolkit

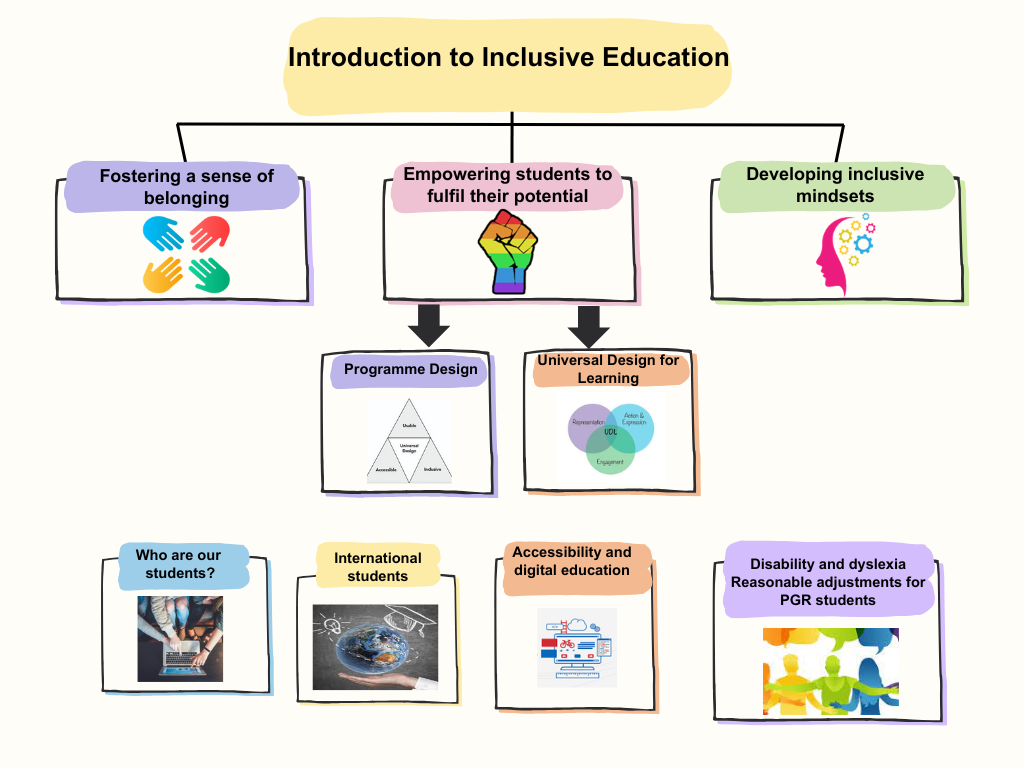

You can now develop your understanding of Inclusive Education by accessing any of the related pages on specific topics, outlined in the map below, which relate to the Inclusive Education Framework. You can jump to any useful topic, as you require.

Workshops

You can also develop your understanding of Inclusive Education by attending workshop sessions that relate to each topic. These workshops can be taken in a live face-to-face session, if you prefer social interactive learning, or can be completed asynchronously in your own time, if preferred. You can find out more information on workshops, and the link to book here

Bespoke School Provision

We offer support for Schools on Inclusive Education, through the Education Development service. This can be useful to address specific local concerns, to upskill whole teams, or to support the programme approval and revalidation process. Please contact your School’s Education Development Team contact for more information.

Map of Topics

Below is a map of the toolkit and workshop topics, to aid your navigation. These will be developed and added to in future iterations of this toolkit:

You’re on page 5 of 9 Inclusivity theme pages. Explore the others here:

1.Inclusivity and the CU Inclusive Education Framework

2.Introduction to Inclusive education

3.Fostering a sense of belonging

4.Empowering students to fulfil their potential

5.Developing Inclusive Mindsets

6.Universal Design for Learning

8.Disability and Reasonable adjustments

Or how about another theme?

References

Arao, B., & Clemens, K. (2013). From safe spaces to brave spaces. The Art of Effective Facilitation: Reflections from Social Justice Educators, pp. 135-150.

Arshad, R. 2021. Decolonising the curriculum: How do I get started? https://www.timeshighereducation.com/campus/decolonising-curriculum-how-do-i-get-started

Bamford, J. And Pollard, L. 2019. Cultural Journeys in Higher Education: Student Voices and Narratives. Bingley: Emerald Publishing

CAST. 2021. Universal Design for Learning Guidelines. Available at: https://www.cast.org/impact/universal-design-for-learning-udl

Healey, M. Flint, A. Harrington, K. 2016. Students as Partners: Reflections on a Conceptual Model Teaching and learning inquiry, Vol.4 (2), p.1-13

Open University. 2018. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion in the Curriculum. (Online) Available at: https://www.open.ac.uk/equality-diversity/sites/www.open.ac.uk.equality-diversity/files/files/EDI%20in%20the%20curriculum%20final%20-%20Julie%20Young-28Feb19.pdf

Parsons, L. and Ozaki, C.C. 2020. Teaching and Learning for Social Justice and Equity in Higher Education. Swizerland: Springer

Perez, R. J. , Robbins, C. K. , Harris, L. W. & Montgomery, C. (2020). Exploring Graduate Students’ Socialization to Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 13 (2), 133-145

UAL 2023. Decolonising Pedagogy and the Curriculum. (Online) Available at : https://www.arts.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0035/228986/AEM-Decolonising-pedagogy-and-the-curriculum-PDF-224KB.pdf (accessed 30/3/23)

Zirkel, S. (2008). The Influence of Multicultural Educational Practices on Student Outcomes and Intergroup Relations. Teachers College Record, 110(6), 1147-1181. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146810811000605

Share Your Feedback